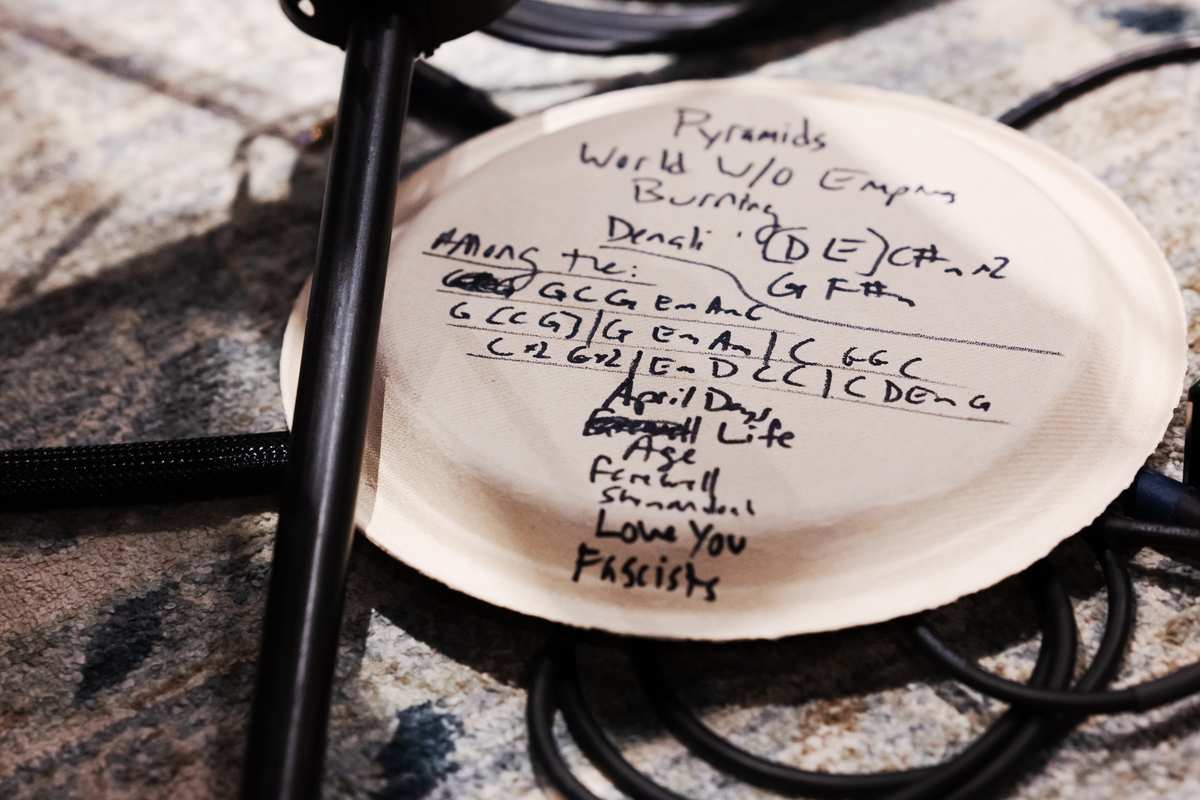

The set list for Frazier’s show on a plate onstage at Bright Box Theater on May 16.

12:10 JST, September 7, 2025

The songwriter was unconscious, but his voice filled the operating room.

Mike Frazier’s dirty-blond locks had been partially shaved and his head sanitized. The surgeon standing over him slid his blade in a crescent over Frazier’s right ear and tugged his scalp into position, holding it in place with a dozen sky-blue clips.

Then he began opening a window into the musician’s brain.

The surgeon, Lee Selznick, had chosen a Spotify playlist of Frazier’s music for the delicate procedure that would take three hours and would later marvel at the experience: “We were deep in his head, and listening to the words right out of the very part of him that was producing that beautiful music.”

The task that day was to reach and remove the cause of the grievous pain that had besieged and mystified Frazier for years. After almost a decade as a folk-rock singer with a rollicking vibe and a knack for storytelling, piercing stomach pain had stymied his songwriting and drawn him into a dangerous depression before he turned 30.

The craft that brought him such meaning – writing exuberant anthems, protest songs and intimate tunes about love and family, desert stars and escaping to Alaska – had become a slog, and he couldn’t finish some of the songs he started.

Removing a piece of his brain about half the size of his fist, Frazier and his doctors thought, was his best option for combating a condition that affects about 1 percent of adults in the United States and tens of millions of people worldwide – but that is still often misunderstood and misdiagnosed.

Some people think giving up a piece of their brain means losing a part of themselves, Selznick said. He hoped it would allow Frazier to regain who he was meant to be.

The symptoms

Frazier was driving down Interstate 395 in Virginia, headed for a funeral, when it struck.

“Oh my God, I’m dying,” he thought.

It felt like he was being stabbed in the gut. But the terrifying wave passed. And, back in 2022, he settled on an explanation: It must have been a panic attack.

During the following two years, the excruciating stabbing episodes became a paralyzing part of his life, eventually happening almost every time he ate. There was also intense nausea and vomiting. Doctors suggested it could be a digestive ailment, maybe acid reflux. But that didn’t account for the severity of what he experienced or his broader descent.

People called him “Sunshine” as a kid. In high school in Virginia, he and his best friend, Stephanie Bruno, whom he would later marry, were jointly named “Most Likely to Brighten Your Day.”

But the lack of answers, let alone solutions, for his debilitating pain fed a darkness that seemed to be devouring the life he loved, including his songwriting. Sometimes it felt like he couldn’t come up with a single line.

As time passed, the symptoms worsened. Paranoia began to bleed into the rest of his life, from making music to serving customers at his winery job in Seattle, where he and Bruno had moved. The dread of the pain that might follow any meal seemed to spread, and he became haunted by imaginary dangers. He’d loop around the block three times, terrified he had run someone over. He feared he might blurt out something unhinged while performing, or end up in some kind of fight.

One night, he kept looking at his Boston terrier, Cannoli, terrified something horrible might suddenly happen to her. “I feel like I’ve lost every essence of my mind,” he recalled thinking.

He frantically called and texted Bruno, who was in Virginia. He turned to her, desperate and suicidal.

“I know without a doubt Steph saved my life that night. If I didn’t have her calming me down, I don’t think I’d be here today,” Frazier said.

About a week after that episode, he was meeting a family friend back in his hometown of Winchester, in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. They were together to share memories of their godfather after his funeral. Frazier had taken to subsisting mostly on plain yogurt, apples and other bland food, trying but failing to keep the attacks from flaring.

His lunch companion, Ben Hethcoat, watched for about a minute as Frazier’s jaw went slack, his expression went blank and his hands started convulsing.

Frazier felt a wave of nausea he thought lasted only a second or two – then picked up the conversation where they left off. Hethcoat was startled. Though he didn’t say anything right then, alarm bells went off, and that night they talked about what happened.

Early the next morning, Frazier had an MRI and got in to see Paul Damien Lyons, a neurologist who has practiced for more than 20 years in Northern Virginia. With electrodes stuck to Frazier’s scalp, the roaring pain that had been haunting him returned.

At that exact moment, Frazier’s brain made a powerful recording of its own, one that answered the question that had eluded him: Lyons was able to pinpoint an area of Frazier’s brain where a cluster of nerve cells was misfiring.

The diagnosis

The brain is a mammoth network of about 86 billion neurons, cells that communicate using electrical and chemical signals to shape a person’s thoughts, emotions and actions. The routes followed by those signals, as the mind goes about its endless tasks, are called circuits, and one of Frazier’s had gone haywire.

When the delicate balance of those signals gets disrupted, experts say, it can lead to epilepsy – and that was Frazier’s diagnosis. The condition is marked by recurring seizures that can range from brief and subtle to convulsive and severe, and that can bring an increased risk of death.

Despite numerous medical advancements, ignorance and stigma associated with epilepsy have led many people to try to keep it secret, while others, such as Frazier, remain in the dark and miss out on an early diagnosis.

The convulsive seizures in popular portrayals, where patients jerk erratically, biting their tongues, miss the more subtle cues that frequently characterize epilepsy, Lyons said.

One of Lyons’s epilepsy patients simply became uncharacteristically quiet. Another, a senior citizen who became disoriented and had problems with language, was misdiagnosed with dementia. A third, a teenager, had seizures that mimicked psychosis, leaving her agitated, combative and confined in psychiatric hospitals.

For two years, Frazier had premonitions of impending doom, along with the severe stomach problems that made it difficult to eat. “In fact, those were all symptoms of seizures,” Lyons said. Even with Bruno’s own epilepsy diagnosis years before, which followed obvious seizures, the couple hadn’t considered that Frazier might be facing the same thing.

Lyons says about two-thirds of people with epilepsy can achieve “seizure freedom,” as doctors call it, using one of many available medicines. Others who have drug-resistant epilepsy can have surgery to remove or otherwise destroy the problem cells, or can use an implant to treat them.

Delaying a diagnosis can have serious consequences. Lyons said your brain can, in essence, get good at seizures in the same way it can get good at playing the piano. “Pathological learning,” he called it.

“Not all learning is good. There’s pain, right? There’s PTSD. There’s addiction. Those are all circuitries of learning. Epilepsy is a circuit like everything we do,” Lyons said. “Unfortunately, epilepsy, the more it occurs, the more that circuit’s used, the more effective the brain becomes at seizing.”

Frazier’s brain kept getting better at pulling him down.

The surgery

After cutting quarter-size holes in his head, then using a bigger drill to connect the openings, Selznick lifted off a piece of Frazier’s skull. It was about the diameter of a teacup. He sliced through the protective membrane beneath, called the dura, then reached the bumps and grooves of Frazier’s brain.

Frazier chose to have surgery because doctors weren’t sure whether the abnormal cluster of cells sparking his problems might be a slow-growing cancer or caused by a congenital condition.

The surgeon targeted the area with the misfiring cells, toward the front of his right temporal lobe, just above his ear, using handheld forceps with an electrical tip to melt tissue and prevent bleeding. There could be other “irritable” clusters of cells nearby contributing to Frazier’s pain. So Selznick removed those too.

It’s an area that manages smelling, tasting and digestion, and so related symptoms are commonly paired with seizures.

He stitched up the dura, reattached the piece of skull with titanium screws and plates, and closed Frazier back up with 37 staples.

Frazier woke to what he called insane pain, partly from an incision affecting the muscle that controls his jaw. Selznick gave him a fist bump and said he sounded like Neil Young when he sang. It had all gone well.

Frazier’s seizures, and the stabbing pain that came with them, were gone. And a biopsy would show the tissue was not cancerous.

Still, he didn’t understand the way his mind was working after the operation. He initially couldn’t figure out how to play his guitar. And he wasn’t experiencing the sudden improvement in his mental health he had expected.

“I just assumed, well, the minute they cut this thing out of my brain … I won’t feel depressed anymore,” he said.

Music became a tool in his recovery – and a way to process his trauma before the operation. He leaned on songwriting to try to capture the struggles, and the stirrings of hope, that followed. He explored his mind being out of control in a song titled “What’s Wrong With Me?” Then, amid sleeplessness and severe pain, he imagined dancing California redwoods in a rousing follow-up. A playful exploration of extraterrestrials came next.

In one disturbing moment, he was sure he no longer sounded like himself. So he wrote that into a song too.

Then came a breakthrough.

He first noticed something was happening in July last year while sitting outside reading Bruno’s recently published novel. He remembers ripping through 20 pages faster than he had ever read anything.

Then on another morning soon after, he woke up and – for the first time in his life – had an opening verse and melody waiting in his head. It was an anti-war song. He had been writing songs since he was 13 and heard other songwriters talk about that happening to them, but he was deeply skeptical.

For him, the process of songwriting had always been about putting together puzzle pieces. “Okay this verse might be cool, and then I’ll write a couple more, and then I’ll put this line here and this line there,” he said.

But on this morning, the words and notes flowed.

“Man, that was sweet,” Frazier thought.

The operation had left him physically scarred and wrestling with recovery. But it was also freeing. “It felt like, I mean, I literally had a blockage removed, you know?”

He recorded the start of the song on his phone so it wouldn’t evaporate, got himself to the couch, and finished “World Without Empires” that morning.

“At that point, I think I’m like firing. Reading is easier. Writing is easier. Mental processing. I go in the kitchen, I start cutting up vegetables,” he recalled. Even that blew him away. He’d worked in kitchens since he was 18, and he’d never diced an onion with such speed.

He launched into another song.

Sun streaming through the bay window woke him around 5 a.m., so he just started writing. The initial bones for “One Day I’ll Find It” came quickly. He got most of the lyrics down in his notebook with his black pen that day, crying much of the way through.

Thinking about how

I almost lost my mind

Thinking about how

It breaks my heart each time

That would become part of a 10-song musical diary chronicling his healing, and his seventh album.

The effects on Frazier’s songwriting are probably rooted in some of the deeper complexities of epilepsy, his doctors said. There are many electrical problems that aren’t as severe as a full-blown seizure but still leave a mark.

Lyons said researchers using implanted monitoring devices found that patients who have one seizure a week might also have hundreds of “small discharges” every day of only a few seconds each. Those and other even shorter blips “may be significant enough, on an electrical basis, to cause poor cognitive function,” he said.

Frazier’s surgery probably removed that type of “abnormal background signal,” which could help explain the restoration, and even sharpening, he has described in his songwriting.

Selznick agrees. It’s like being in a room with an incessant buzzing, he said.

“Then it stops, and you didn’t even realize how stressful that was,” Selznick said. He added that Frazier’s relief from the intense emotional stress of thinking he was losing his mind and getting back to the life he wanted to lead “goes a long way too.”

The healing

Frazier stood in a former jeans-and-overalls factory packing up his guitar this past fall, when a guy walked over to see if he might be up for playing some more.

He and a group of friends from D.C. were on a bonding trip in the Shenandoah Valley, and they set out for the Woodstock Brewhouse hoping for some live music along with the Tipsy Squirrel ale and other offerings.

“Hey, man, I’m tired,” Frazier said. “I had brain surgery a few months ago.”

Adam Gebremedhin asked him why, and he told him.

“You’re one of us,” Gebremedhin said.

They were part of an epilepsy support group and had no idea they would be listening to an artist that evening who shared their condition.

As Frazier plugged his guitar back in and started playing the songs he had written, sometimes through tears, he looked out at their long table and saw another member of the group sobbing.

“It was a cosmic moment,” Frazier said.

Gebremedhin stood and began to cheer, turning around to see his friends’ faces. “We were all just like open eyes, no blinks, just looking at him, listening,” he said.

Members of the SHARE Meetup group had come together to discuss their epilepsy stories earlier that day. His became more severe after a drunk driver hit him on the sidewalk, smashing his head. It had gotten him fired from his job as a physical therapist, with bosses fearful of his seizures, he said.

Seeing Frazier up there, refusing to retreat from the music he loved, “really did change my thoughts on how I should not let epilepsy control me,” Gebremedhin said.

A few months later, in April this year, Frazier told Bruno it was the first day that he woke up and didn’t feel like he was in survival mode. He had made it through. Bruno could see it coming in the weeks before. “There was one day where I was like, ‘Mikey’s back!’” she said.

A few days later, Frazier released his latest record. “April Days” came out on April 25, a year to the day after his surgery.

Frazier came back to Winchester in May and looked out at the hometown crowd. Lee Selznick, his surgeon, sat across from the stage. Frazier’s parents danced up front, and Bruno came up to sing a few songs with him. He sang a haunting remembrance of his grandfather.

Frazier thanked his doctors for saving his life and ended with his own sing-along:

I’m gonna heal … I’m gonna heal … I’m gonna heal … my … mind

Then he threw it to the crowd, which came through:

We’re gonna heal … we’re gonna heal … we’re gonna heal … our … minds

He let his voice fade behind theirs. Then he left them with a question that seemed more like a declaration.

“Won’t it be just fine?”

Top Articles in News Services

-

Prudential Life Expected to Face Inspection over Fraud

-

Arctic Sees Unprecedented Heat as Climate Impacts Cascade

-

South Korea Prosecutor Seeks Death Penalty for Ex-President Yoon over Martial Law (Update)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

-

Suzuki Overtakes Nissan as Japan’s Third‑Largest Automaker in 2025

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

China Confirmed to Be Operating Drilling Vessel Near Japan-China Median Line

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time