30 Years After Sarin Attack — Lessons Learned / Former Police Officials Talk about Lessons Learned from Their Responses to Cult’s Actions

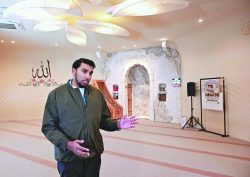

Shozo Jin speaks in front of the Kasumigaseki subway station in Chiyoda Ward, Tokyo, on March 11.

The Yomiuri Shimbun

12:58 JST, March 20, 2025

This is the second installment of a series that examines the scars left by the Aum Supreme Truth cult’s chemical attack on the Tokyo subway system on March 20, 1995, and explores the lessons learned from that tragedy.

Shozo Jin was examining brand-new chemical protection suits on the 16th floor of the Metropolitan Police Department’s headquarters in the Kasumigaseki district in Chiyoda Ward, Tokyo, on March 20, 1995.

Jin, now 75, was in charge of equipment procurement at the MPD’s security bureau at the time, and the first police search of Aum Supreme Truth’s facilities in the then village of Kamikuishiki (now part of the town of Fujikawaguchiko), Yamanashi Prefecture, was scheduled to take place just two days later.

There were strong suspicions that the cult was involved in the production of sarin, a highly toxic nerve agent. Preparations were underway to unveil the protection suits, made for emergency situations, to the MPD Superintendent General and others.

Shortly after 8:20 a.m. on the day, tense emergency calls were circulating over police radio. They revealed that people had collapsed from a pungent smell in the Tokyo subway system. Hearing reports that people were foaming at the mouth and vomiting blood, Jin said he intuitively felt that the cult was behind the havoc.

Jin and three others hurriedly formed a response team. Wearing gas masks, they went down the stairs of Kasumigaseki Station. Jin said he was prepared to die at the time.

Jin lowered himself through a half-open window of a Hibiya Line train car. He scraped up some liquid-like substance, which had apparently leaked from a plastic bag found nearby on the floor, with his gloved hands. The bag had been wrapped in newspaper.

When he returned to the platform, a crime lab investigator wearing a regular face mask approached him to take a photo of the recovered items but then fell backward.

At 11 a.m., the MPD announced that the substance scattered in the subway system was “highly likely to be sarin.” Jin and his team went to two more stations and recovered more samples.

At Kasumigaseki Station on the Chiyoda Line, a bag containing sarin was kept in a safe in the station building. After returning to the police headquarters, Jin and the other team members suffered symptoms of miosis, in which the pupils constrict and one’s vision darkens. They are believed to have inhaled gas from the substance that was still on their protective clothing when taking the suits off.

“We didn’t have sufficient knowledge of chemical terrorism,” Jin said. “We weren’t well-prepared for such attacks, either.”

Although he retired in 2010, he continues to talk about his experience to younger people in the police to prevent the incident from being forgotten.

Investigators enter a facility of the Aum Supreme Truth cult in Fujinomiya, Shizuoka Prefecture, on March 22, 1995.

Did not expect ‘preemptive attack’

Takashi Kakimi, now 82, said he felt as if he had lost all his strength as he heard the news of the sarin gas attack on the subway system. Kakimi was the chief of the Criminal Investigation Bureau of the National Police Agency at the time, and he was at his office in Kasumigaseki on March 20. Kakimi had suspected a connection between the cult and the nerve gas over the past six months, but a “preemptive attack” by the cult was something he had not expected.

At the beginning of August 1994, Kakimi received a phone call from the Nagano prefectural police chief telling him that a company related to the cult had purchased a large quantity of chemicals that could be used to make sarin. The purchase was discovered during the investigation into the sarin nerve gas attack by the cult in Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture, in June 1994.

On Aug. 8, 1994, the Kanagawa prefectural police, who were investigating the 1989 murder of lawyer Tsutsumi Sakamoto and his wife and son, reported to Kakimi that Aum had mentioned sarin in their magazine before the Matsumoto incident. Kakimi said his perception then changed from seeing Aum as a “peculiar group” to a “dangerous cult.”

On Sept. 6, 1994, Kakimi set up a team of about 10 investigators that exclusively worked on Aum cases in the NPA’s First Investigation Division.

The Nagano prefectural police collected soil samples from the area around the cult’s facilities in the former Kamikuishiki village, where a bad smell had been reported, in October 1994. On Nov. 16, 1994, the police received test results that showed residual substances from sarin production had been detected in the soil samples.

As the findings revealed a connection between Aum and sarin, Kakimi hurriedly made a plan to search the cult’s facilities, estimating that it would take two to three months to start the investigations.

However, there still was not enough evidence to justify a search. The case was delayed to the following year with no date for the investigations being set.

In December 1994, Aum murdered a man and injured another who were supporting a person trying to leave the cult, using the highly toxic VX gas.

The plan for large-scale investigations was compiled on Feb. 24, 1995. Four days later, Kiyoshi Kariya, then 68, the chief clerk of the Meguro Notary Office, was abducted by the cult’s followers in Shinagawa Ward, Tokyo. Kariya was later killed by members of the cult.

With the full-scale participation of the MPD in the investigations, charges against the cult were finalized. A team of about 2,500 investigators hurriedly prepared for the searches in the days leading up to March 22. However, the cult carried out the sarin gas attack on the subway system before they were due to start.

There is no record of a full investigation into the NPA’s responses to the cult, including those regarding the attack on the subway system in which more than 6,000 people were killed or injured.

“Why did the police fall behind Aum? Those in charge of the investigations at the time should give a full explanation now,” a former senior police official said.

Takashi Kakimi speaks in an interview.

Missed opportunities

As a main factor behind the delays to moves by the police, Kakimi pointed to investigators’ lax responses to 85 cases reported to the police nationwide, including complaints, consultations and missing person cases involving the cult.

Since many of these cases were related to religious issues or domestic disputes, police departments in various parts of the country are believed to have not taken action, especially when it was difficult to judge whether they were criminal cases.

“The police might have been able to nip the problem in the bud before the cult grew large and violent if they did not judge the cases by their own yardstick and had carefully examined each one,” Kakimi said.

The 1996 White Paper on Police listed aspects that were inadequate in dealing with Aum-related cases. They included the lack of knowledge about advanced science and technology, including on nerve agents such as sarin, and the limitations on the authority of the prefectural police outside their jurisdiction, which hampered the NPA from promptly participating in the investigations of the cult.

In light of this, the Police Law was revised to allow prefectural police to conduct investigations even in cases outside their jurisdiction in serious matters.

“The revision has led to the establishment of a perspective on wide-ranging investigations within police departments, allowing them to mobilize their strength nationwide to deal with organized crimes,” said Masahito Kanetaka, 70, who headed the MPD’s second investigation division at the time of the sarin attack on the subway system.

Kanetaka led the team investigating cases involving cult members, including those of perjury and defamation. He has also served as the head of the MPD’s criminal investigation department and the commissioner general of the NPA.

The police now confront new threats, such as so-called lone offender attacks, in which an individual fashions a weapon and commits an offense alone, and “tokuryu” — anonymous and fluid criminal groups whose members connect via social media and repeatedly come together and disperse to commit crimes. These groups are involved in so-called dark part-time jobs and special fraud.

Asked what lessons can be learned from the police responses to the sarin gas attack on the subway system, Kakimi said: “It’s important to go one step beyond what you expect without neglecting even small signs. As society becomes more complex, you need to be even more imaginative than you were 30 years ago.”

Most Read

Popular articles in the past 24 hours

-

Voters Using AI to Choose Candidates in Japan's Upcoming General ...

-

Japan's Snow-Clad Beauty: Camellia Flowers Seen in Winter Bloom a...

-

Monkey Strikes Junior High School Girl from Behind in Japan's Yam...

-

Genichiro Inokuma's Mural in Ueno Station That Gave Hope in Postw...

-

Senior Japanese Citizens Return to University to Gain Knowledge, ...

-

Foreign and Security Policy: Political Parties Must Discuss How T...

-

Heavy Snow Linked to 30 Deaths across Japan since Late Jan.; JMA ...

-

Tokyo Police Arrest Head of Resignation Assistance Firm

Popular articles in the past week

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock ...

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefectu...

-

Foreign Snowboarder in Serious Condition After Hanging in Midair ...

-

Chinese Embassy in Japan Reiterates Call for Chinese People to Re...

-

Narita Airport, Startup in Japan Demonstrate Machine to Compress ...

-

Toyota Motor Group Firm to Sell Clean Energy Greenhouses for Stra...

-

Sakie Yokota, Last Surviving Parent of a North Korea Abductee, Ur...

-

Beer Yeast Helps Save Labor, Water Use in Growing Rice; Govt Hope...

Popular articles in the past month

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disa...

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizz...

-

China Confirmed to Be Operating Drilling Vessel Near Japan-China ...

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance,...

-

M6.2 Earthquake Hits Japan's Tottori, Shimane Prefectures; No Tsu...

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock ...

-

Japan, Qatar Ministers Agree on Need for Stable Energy Supplies; ...

-

Japan, Italy to Boost LNG Cooperation; Aimed at Diversifying Japa...

Top Articles in Society

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

Record-Breaking Snow Cripples Public Transport in Hokkaido; 7,000 People Stay Overnight at New Chitose Airport

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

-

Foreign Snowboarder in Serious Condition After Hanging in Midair from Chairlift in Nagano Prefecture

-

Train Services in Tokyo Resume Following Power Outage That Suspended Yamanote, Keihin-Tohoku Lines (Update 4)

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

China Confirmed to Be Operating Drilling Vessel Near Japan-China Median Line

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time