Extraordinary Diet Session Closes: Will ‘Politics And Money’ Issue Be Brought to An End?

15:55 JST, December 25, 2024

Although there are points left unresolved, it is noteworthy that the prospect of a solution to the issue of “politics and money” has finally come in to view. This is evidenced, for example, by the realization of a further revision to the Political Funds Control Law.

On the other hand, the government’s emphasis on keeping in step with the opposition parties’ demands on policy issues and the makeshift nature of the answers it ended up giving were underwhelming.

The extraordinary Diet session has come to a close.

The Diet passed three bills related to political reform, which was a focal point, mainly on the total abolition of political activity funds provided by a political party to its senior members and other lawmakers, as well as the establishment of a third-party body in the Diet to monitor the spending of political funds.

In addition, the revised annual payment law for Diet members has been enacted. Lawmakers are given ¥1 million a month to cover “survey, research, public relations and accommodation costs” — previously known as “document, correspondence, travel and accommodation expenses” — and are now required to disclose spending by providing receipts and then refund the remainder to the national treasury.

During negotiations between the ruling and opposition parties, the handling of donations from companies and organizations was not settled, and they agreed to continue discussions to reach a conclusion by the end of March. Although such “homework” remains, if the series of reforms will lead to greater transparency of political funds, it can be considered a step forward.

Besides, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party intends to donate a certain amount of money in relation to some party members failing to record funds they received in their political funds reports. The amount is said to be about ¥700 million. The LDP seems to be aiming for an early settlement of this issue, but it is not clear where or in what form the donation will be made.

At his first Budget Committee meetings since taking office, Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba repeatedly stated that the supplementary budget for the current fiscal year, totaling ¥13.9 trillion, was “necessary to exit from deflation.” His answers were marked by hackneyed words.

The debate between the ruling and opposition parties did not touch on the financial resources needed to raise the ¥1.03 million annual “income barrier,” the threshold for the imposition of income tax. Measures included in the supplementary budget which could be criticized as lavish budgetary handouts, such as the provision of ¥30,000 in benefits to households exempt from residential taxation, did not become a major point of contention either.

Resolving the issue of how far to raise the ¥1.03 million threshold has also been passed over to the ordinary Diet session. The government and ruling parties are considering amending the budget proposal and related tax system reform bills depending on how the opposition parties respond. However, the fact that they are anticipating the possibility of such amendments in advance is in itself unprecedented.

Budget proposals and policies are supposed to be formulated in accordance with a desired vision and goal. The current administration lacks such a perspective, and one cannot help but question the quality of its insights.

Ishiba has said for some time that he will “follow the previous administration” in economic policy and leaves everything to the relevant Cabinet ministers, but does he have any intention of restoring Japan’s presence? It will be unacceptable if a leader tasked with steering national politics cannot even present a vision for the economy.

(From The Yomiuri Shimbun, Dec. 25, 2024)

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

40 Million Foreign Visitors to Japan: Urgent Measures Should Be Implemented to Tackle Overtourism

-

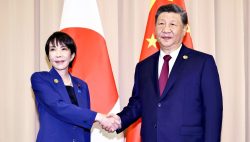

China Criticizes Sanae Takaichi, but China Itself Is to Blame for Worsening Relations with Japan

-

Withdrawal from International Organizations: U.S. Makes High-handed Move that Undermines Multilateral Cooperation

-

University of Tokyo Professor Arrested: Serious Lack of Ethical Sense, Failure of Institutional Governance

-

Defense Spending Set to Top ¥9 Trillion: Vigilant Monitoring of Western Pacific Is Needed

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan, Qatar Ministers Agree on Need for Stable Energy Supplies; Motegi, Qatari Prime Minister Al-Thani Affirm Commitment to Cooperation