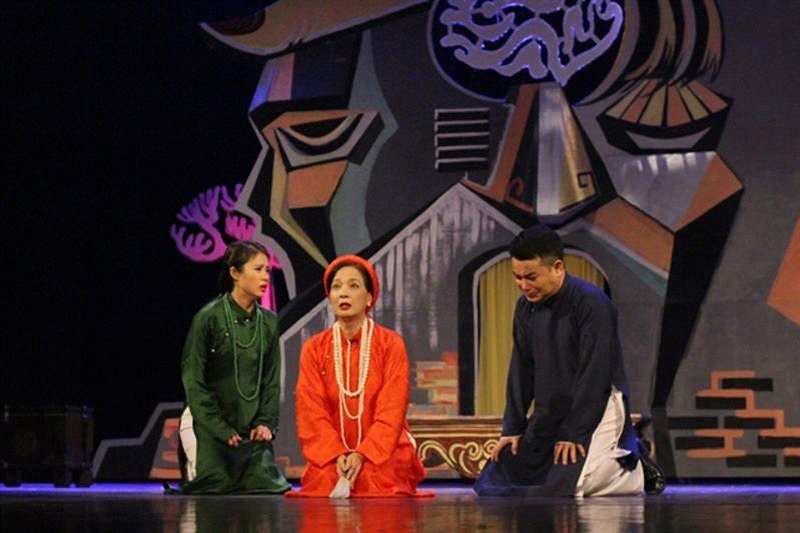

“The Cup of Poison” is performed to celebrate the 100th anniversary of local Western-style theatrical plays in Vietnam.

November 5, 2021

The thousand-year-old culture of Vietnam is so rich in theatrical tradition — be it plays, comedies, tragedies or musicals — that each region seems to have its own operatic form.

The north has the hugely popular cheo plays performed in village courtyards for the entire public to enjoy. The center possesses the more sophisticated, in-depth tuong plays, often taking place in roofed venues and performed for royalty, while the south has the heart-stopping melancholic tunes of cai luong plays and their lengthy lyrics that include up to 99 words in a single breath.

While tuong (classical drama) and cheo (popular opera) were traditional theatrical plays, cai luong (reformed drama) was a renewed musical style born in the early 20th century by incorporating vong co (nostalgic) melodies into the plot.

Around the same time, a Western genre of performing art called kich noi (straight play), also made its debut in the country. With the premiere of “Chen thuoc doc,” or “The Cup of Poison,” penned by playwright Vu Dinh Long in 1921, the Western-style play — without singing — was born. The genre is now celebrating its 100th anniversary in the country.

The beginning

Theatre critics are agreed that such plays came to Vietnam with the French long after they invaded the country, at some point during the latter half of the 19th century.

The first French play performed in Hanoi in Vietnamese language, translated by Nguyen Van Vinh, premiered in the city’s Opera House on April 20, 1920. It was “Le Malade Imaginaire,” or “The Imaginary Invalid,” by Moliere. The Tien Duc Open Mind Society co-sponsored the premiere to raise funds for the families of Indo-Chinese soldiers who fought for France in World War I and never came back.

During that time, such plays were only popular among the ruling French and some Western-trained local intellectuals, while most audiences preferred singing in their performances.

A year and a half after the Moliere premiere, Vu Dinh Long presented his play “The Cup of Poison” at Hanoi’s Opera House, and more local playwrights began penning their own scripts.

Phong Hoa and Ngay Nay newspapers even ran readers’ scripts sent from around the country.

Vu Dinh Long, now known as the father of Vietnamese theatre, made his name in the early years of the 20th century, owning the Tan Dan Publishers and various publications, namely Tieu thuyet thu bay (Saturday Novel), Pho thong ban nguyet san (Popular bi-monthly magazine) and Huu Ich (Useful).

He associated with both literary circles and the wider market, and played a major part in the national literary, newspaper and publishing scene of the time.

At 25 years of age, he penned “The Cup of Poison” and “Toa an luong tam,” or ”The Court of Conscience,” ushering in an entirely new genre of performing art throughout the country.

In a conference on Vu Dinh Long’s life and works earlier this month, critic Ngo Tu Lap said that The “Cup of Poison” had an impressive launch not only thanks to its new format, but for the way it cut into urban family crises, reflecting the larger societal conflicts and issues of the country in the early 20th century. He said that the play also showed its author’s in-depth dissection of the tossing and turnings of what were then degrading social norms and values.

Long went on to write other plays reflecting contemporary issues, including “Dan ba moi,” or “New Women,” and many more.

Trained in French culture and education, he also translated other world-famous plays such as Shakespeare’s “Hamlet,” Corneille’s “Motherland” and Chekhov’s “Uncle Vanya” with the adapted Vietnamese name Uncle Van.

In 1935, poet The Lu, who also wrote some of Vietnam’s best crime and detective novels, founded The Lu Theatre Troupe in Hai Phong with his friend. It was the country’s first theatrical troupe, tilting toward professionalism.

During the brief period of less than two years when President Ho Chi Minh declared Vietnam’s independence in 1945 and before they had to retreat to the mountains in the north for a nine-year long war of resistance against the French, theatrical plays flourished in Hanoi. Small groups between five and 10 people got together to perform, and often even bigger groups.

The form was a useful way to communicate to the wider public, with plays written to commemorate heroic ancestors and call on the masses to rise up against the French colonialists.

Clear prose that was sharp and easy to grasp was a popular quality of theatrical plays, and even inspired the common people to go to evening classes to learn to read and write to reduce the illiteracy rate and encourage economic production.

After the Ho Chi Minh Government had to evacuate to the mountains, back in the cities of Hanoi and Saigon, western plays came back to the stage with plays of Moliere, Shakespeare, and others focusing on the history of the Orient and Vietnam.

Theatrical plays became a subject taught at the Saigon National Academy for Music and Drama. Kim Cuong, a cai luong star, and successor of a Nguyen King also made her name playing in these dramas without singing.

During the time when the country was divided in two, plays also saw triumphant growth in the North, with schools shows and students taking part across the board.

Language students even staged plays in French and Russian. The best theatre actors and actresses were treated like rock stars.

The stars

Prior to the new reforms and radical thinking in 1986, the way the country was economically run was inefficient and theatres could not afford to keep staff fully paid. But the Government soon eased its controls, allowing private troupes to stage public performances.

New scripts were blooming with names such as The Ngu, Doan Hoang Giang and Luu Quang Vu, who all wrote about the pains and joys of Vietnamese society, gradually replacing theatrical productions of political content.

Vu, the most successful playwright of that brief bloom, penned scripts to full houses from north to south. Scouts from theatre troupes came to his home in Hanoi waiting to fetch the latest play exclusively for their theatres.

Many stars were born from those days becoming pivotal artists with superb skill. People’s artists Hoang Cuc and Tran Van, Hoang Dung and Le Khanh were a few of Vu’s artistic disciples.

But this renaissance did not last long. In 1988, a car crash killed Vu, his wife and their youngest son. In 2000, he was posthumously awarded the Ho Chi Minh Prize for his play “Lois The Thu Chin,” or “The Ninth Pledge.”

Though the Vietnamese economy has flourished since 1986, the theatrical scene has not much improved, with people increasingly turning to forms of mass entertainment such as video tapes, DVDs and, today, online streaming. Most theatrical entertainment is watched on screens in the home.

The number of people frequenting cinemas, or theaters has decreased sharply since 2000. Artists have to work odd jobs to make ends meet and theater group managers struggle to tickle audiences and lure them to the theaters.

Plays are a wonderful way to combine an artistic vision, while presenting contemporary issues and capturing an audience’s attention, and it is hoped that after a century of performances they will still be able to flourish.

Top Articles in World

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

North Korea Possibly Launches Ballistic Missile

-

Chinese Embassy in Japan Reiterates Call for Chinese People to Refrain from Traveling to Japan; Call Comes in Wake of ¥400 Mil. Robbery

-

Russia: Visa Required for Visiting Graves in Northern Territories, Lifting of Sanctions Also Necessary

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan