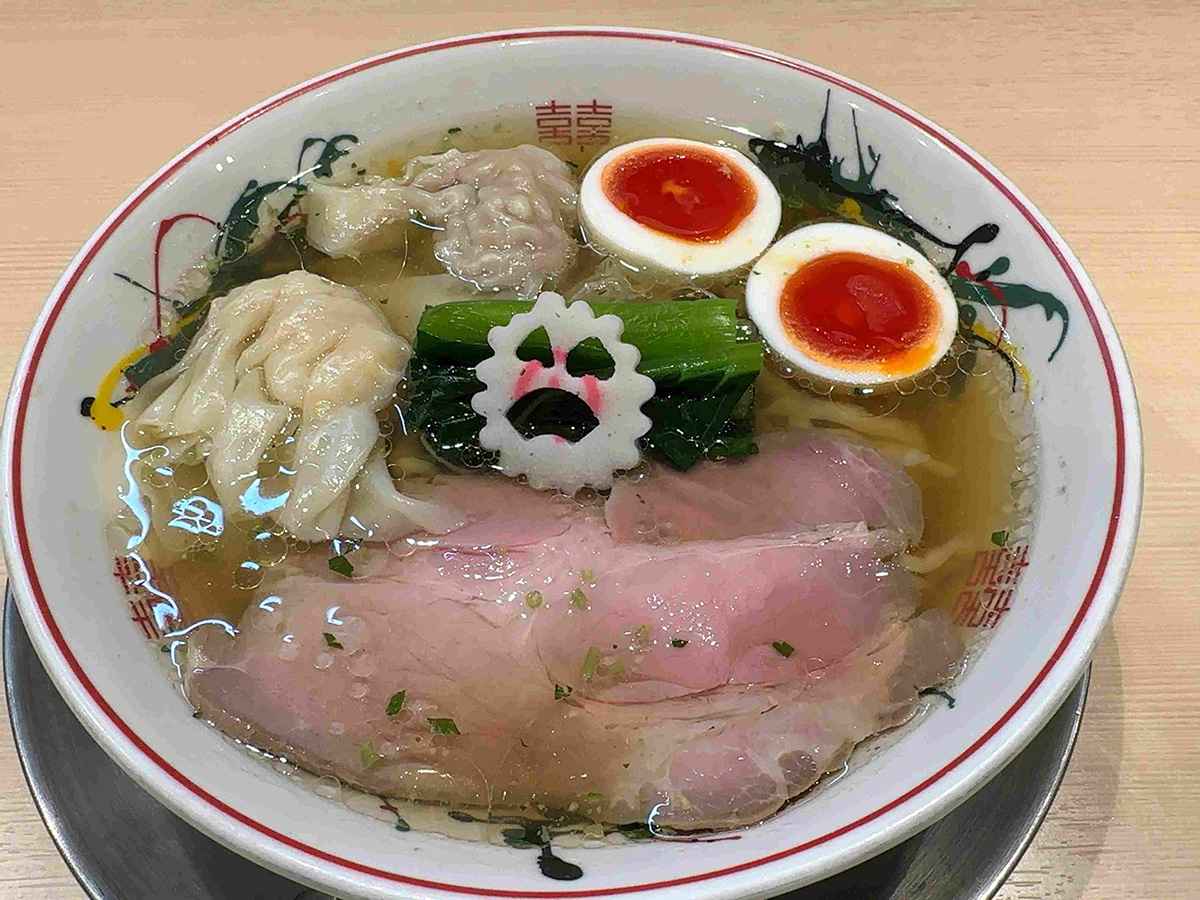

The zenbu-iri (everything-in) shirodashi ramen dish (¥1,360 ) comes with four large wontons

11:04 JST, March 10, 2023

Landing a Bib Gourmand name-check in the Tokyo Michelin Guide is no small feat. However, the King Seimen ramen outlet in Oji, Kita Ward, more than deserves the accolade.

Seimen means “noodle production” in Japanese, but the majestically monikered eatery is no mere noodle factory. I was tipped off about the shop by a Kita Ward government official while covering events in the area, and I wasn’t disappointed. King Seimen’s homemade noodles and filled wontons left a deep impression on me, and the atmosphere, service and comfortable interior were top-notch, too.

The proprietor, Hiromitsu Mizuhara — still only in his thirties — is something of a cause celebre in the ramen world. All five of his central Tokyo ramen stores have proved immensely popular. Indeed, more than one has been singled out by the Tokyo Michelin Guide and they regularly rank among the 100 best ramen shops on Tabelog, a popular restaurant-rating website in Japan.

To reach King Seimen, I left the north exit of JR Oji Station, strolled along a cherry tree-lined path in Otonashi Water Park — set to be illuminated from March 18 — and ambled down the old street that leads from Otonashi Bridge. A tall, good-looking guy standing outside the shop greeted me with a smile, saying: “You must be Mr. Mori. Pleased to meet you, I’m Mizuhara.” His warm welcome made a delightful first impression.

-

A noren (curtain) details the shop’s wonton noodle dishes

-

Exterior view of King Seimen

-

A wonton noodle sign outside the shop

-

The shop name features on a wall plaque at the entrance

-

Otonashi Water Park seen just before its cherry blossoms start to bloom

-

King Seimen’s vending machine

My arrival coincided with the post-lunchtime rush, and I used the ticket machine to order one of the shop’s signature dishes, Zenbu-iri (everything in) Shirodashi Ramen (¥1,360).

Mizuhara, 37, made the ramen himself in the spacious kitchen in lieu of other staff. “It’s been a while since I’ve made this dish, you know,” he said, while deftly preparing the noodles, soup, and toppings, as well as boiling the wontons.

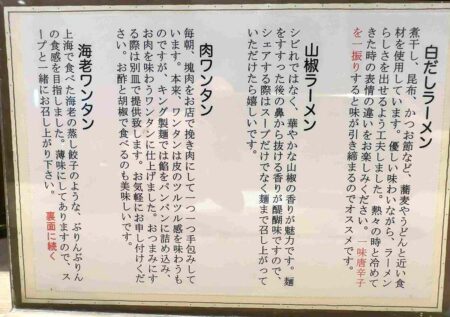

The wontons, which feature on the shopfront’s noren curtain, were perhaps the most impressive part of the meal. The two large meat wontons and two shrimp wontons, resonated with a powerful prandial presence. The shirodashi (white soup stock) was light, shiny, and a delight to the eye. The first sip of the broth had a mild taste, like dashi.

-

The meat wontons are packed full of pork

-

Mizuhara starts to prepare a ramen dish

-

The meat wontons resemble meatballs

-

The shrimp wontons are firm and fresh

“It’s a Japan-inspired [flavor], which I think makes it easy for Japanese people to warm to,” Mizuhara noted.

The soup comprised dried fish, dried bonito flakes and shiitake mushrooms, among other ingredients, but no chicken or pork. The kaeshi sauce is a proprietary blend of light and white soy sauce, while the oil is made from pork lard, and features mackerel and ginger aromas. “Mackerel flakes are often used in udon noodle soup, and you can add table-supplied ginger to the udon” Mizuhara explained. He also noted that the oil used with the ramen broth is a key ingredient in udon dishes.

The handmade meat and shrimp wontons were stuffed full. Plump and delicious, they were also larger and more filling than most regular wontons. The shop’s meat wontons are made by mincing 100% pork — which is used for the shop’s chashu pork dish — into meatballs. The shrimp wontons, meanwhile, use odorless chicken as a binding agent, so as not to spoil the aroma of the shrimp, ginger and spring onions. Due to their size, the wontons take a long time to boil, so the dough skins, or wrappers, must be thick and resilient. King Seimen’s wonton skins are custom-made by a specialist firm. Mizuhara was aware that many ramen shops sell chashu pork noodle dishes, but he also knew that only a few offered wonton noodles. Upon deciding to feature this item on his menus, he was determined to give them a strong personality.

-

The homemade noodles are a perfect complement for the broth

-

Homemade flat, hand-kneaded noodles

-

Soup made with light shoyu (sauce) and shiro (white) shoyu

-

Pouring the soup into a bowl

-

The soup is made from dried bonito flakes, dried fish, among other ingredients

-

Adding kaeshi, a blend of soy sauces

-

A noodle-making machine at the shop. Noodles for Mizuhara’s other other outlets also are made at King Seimen.

The flat noodles mixed well with the soup and had a unique texture. As a lover of homemade noodles, I found them simply delicious. “This is my third ramen shop, but its the first outlet for which we purchased a noodle-making machine to craft our own noodles,” Mizuhara explained. “After the machines produce the noodles, we knead and curl them by hand to imbue them with a different feel.”

The shop uses overseas-sourced flour and has no particular preference for domestic products. Mizuhara said this is because they can rely on a stable supply of necessary products. The hard flour comes mainly from Canada, while the soft flour is imported from Australia and a flour company blends them together. To make the flour even softer, the store merely adds more Australian flour.

King Seimen’s other toppings include homemade pork shoulder chashu, seasoned egg, komatsuna (Japanese mustard spinach), green onion and naruto (fish cake used in ramen dishes).

“I tried to make your dish chock-full of toppings,” Mizuhara said of the finished dish. Indeed, it was a highly satisfying meal, crafted to perfection.

Across-the-board popularity

Mizuhara (left) and staff smile for the camera

In addition to King Seimen, Mizuhara operates four other stores in central Tokyo: Ramen Koike in Kamikitazawa, Setagaya Ward; Chuka Soba Nishino in Hongo, Bunkyo Ward; Tsukemen Kinryu in Kanda-Tsukasamachi, Chiyoda Ward; and Koike no Iekei in Sengoku, Bunkyo Ward. He also runs an affiliated partner shop, Mizuhara Seimen, in Sendai City. Mizuhara is president of the Innocence Corporation in Setagaya Ward, Tokyo, which operates all six shops.

In the 2023 edition of the Tokyo Michelin Guide, three ramen shops are listed with single star, while 18 have been given Bib Gourmand status, which to restaurants that fall short of a star but nevertheless offer great cost performance and high-quality food.

Two of Mizuhara’s ramen shops — King Seimen and Chuka Soba Nishino — figure on the Bib Gourmand list. Tokyo is estimated to have more than 3,300 ramen shops, accounting for about 10% of Japan’s total. In light of these numbers, Mizuhara’s achievement is nothing short of miraculous. Moreover, four of his Tokyo outlets, excluding Koike no Iekei, figured on Tabelog’s 100 Best Ramen Restaurants rankings for 2022.

Always moving forward

Chotto-zutsu sansho (Japanese pepper) ramen (¥1,190 ) is another of the shop’s popular dishes. Chotto-zutsu means “a little bit,” and the meal includes one meat wonton and one shrimp wonton. The light-on-the-palate oil used in the sansho ramen is a combination of soybean oil and sansho.

But how did Mizuhara achieve such success? His reply to this question was somewhat surprising. “[When I started], I only had about six months of experience with ramen. I wasn’t one for going around eating ramen everywhere,” he elucidated. “It’s often the case that ramen aficionados go from place-to-place sampling different shops’ fares and end up wanting to create their own ramen and open a shop. But that wasn’t the case with me at all.”

Mizuhara was born and raised in Naka Ward, Yokohama, and from junior high school until around age 22, he devoted himself to playing in rock and J-pop bands, with the aim of one day turning pro.

While doing so, he also worked at an izakaya pub. At one point, he considered opening his own restaurant someday, but had misgivings, due to being a non-drinker. “If I don’t understand the feelings of people who drink alcohol, running an izakaya will likely be tough,” he recalled thinking to himself.

He then worked for six months at a branch of Rokurinsha, which is famous for its tsukemen (dipping noodles). He remembers thinking at the time that ramen was a somewhat different proposition, however.

Mizuhara was later hired by major yakitori izakaya chain Torikizoku and rose to manage a directly operated branch. “Torikizoku hadn’t gone public at the time, but was looking to do so,” he mused. “If I’d continued working there, I might have had a stable life working in the restaurant industry.”

However, Mizuhara said part of him resisted such a path, and he “wanted to create and express something,” just as he had while making music. After realizing he might be able to survive in the ramen business even without drinking alcohol, he left Torikizoku and, with his wife’s support, opened his first ramen shop in 2013 at the age of 28. This outlet, the forerunner to Ramen Koike, specialized in niboshi (dried fish soup) tsukemen.

The shop thrived, thanks to a tsukemen boom. However, tsukemen-making is harder and more labor-intensive than ordinary ramen, and initially, Mizuhara developed pain in his hands. Another fly in the ointment was that some customers would leave after realizing the shop did not serve ordinary ramen.

To deal with these challenges, Mizuhara began serving light, niboshi ramen as a way to reduce the heavy workload and attract more “traditionally focused” customers. However, with the onset of the niboshi boom, the shop got busier than ever. “After that, I stopped complaining about my hands hurting, and I just kept moving forward,” he recalled. As a result, he now operates multiple shops, including King Seimen, which opened in March 2019, and Koike no Iekei, which launched last October and is the most recent of his enterprises.

-

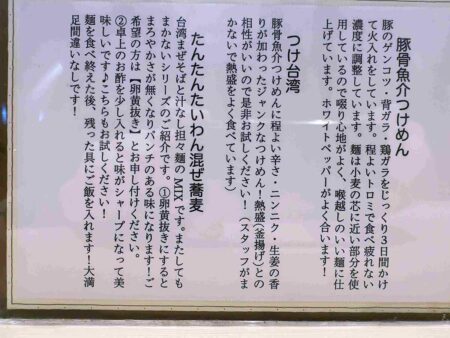

Tsuke Taiwan noodles topped with chashu pork and seasoned egg

-

Tsuke Taiwan soup for dipping noodles

-

Spicy tsukemen, tsuke Taiwan (¥950)

Mizuhara’s discerning palate and management style are major factors in his success, too. While working at an izakaya, his taste buds were cultivated and nurtured by a Japanese cuisine chef who told him “This is what good taste is all about.” Mizuhara has long strived to hold himself to that chef’s same high standards. As for his management sense, he offered, “I value the perspective of ordinary folks who aren’t ramen nerds.”

In the case of King Seimen, Mizuhara carefully considered the shop space, waiting times, comfort and service, before concluding that the shop and kitchen size made it suitable for seating about 10 people at the counter. The store is clean and the floor, unlike some other ramen stores, is not sticky with grease.

-

King Seimen’s counter seating accommodates about 10 people.

-

Explanation of ramen and wontons

-

Tsukemen and Mazesoba Noodles are explained

“To move around the kitchen freely, you can’t be more than 183 centimeters tall. But I’m 188 centimeters, and bump into things all over the place,” he said with a laugh.

King Seimen is located in Oji, which means “prince” in Japanese. The name of the shop was originally supposed to be Prince Seimen, but due to a misunderstanding ended up with a “king” prefix instead.

Mizuhara’s unpretentious and jovial personality have a positive effect on shop’s atmosphere. “I’m interested in the whole world — America, Europe, China — I want to compete globally,” he said, offering an insight into his business goals.

Mizuhara’s powerful way with words is only one of his talents.

King Seimen

1-14-1 Oji Honcho, Kita Ward, Tokyo. Lunch: 11:00 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. Dinner: 5:30 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. Open daily (excluding year-end and New Year holidays).

Futoshi Mori, Japan News Senior Writer

Food is a passion. It’s a serious battle for both the cook and the diner. There are many ramen restaurants in Japan that have a tremendous passion for ramen and I’d like to introduce to you some of these passionate establishments, making the best of my experience of enjoying cuisine from both Japan and around the world.

Japanese version

【ラーメンは芸術だ!】ラーメン界の星、東京・王子「キング製麺」バンドマンが人気店を作るまで

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (2/20-2/26)

-

‘World’s Oldest Bio-Business’ Is Japan’s Seed Koji Retailing, Mold Used to Make Fermented Products like Sake, Miso, Soy Sauce

-

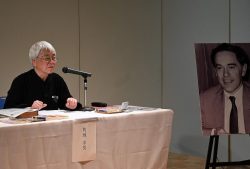

Donald Keene’s Drinking Buddy and Translator Yukio Kakuchi Pays Tribute to Japanologist’s Lifelong Work

-

“The Tale of Genji” Back-Translation Project Led to Touching Encounter with Keene; Poet Sisters Recount Memories of Scholar at Packed Talk Event in Tokyo

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

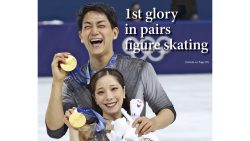

Japan Figure Skating Legend Yuzuru Hanyu Is Proud Disaster Survivor and Gold Medalist, Vows to Continue Support Efforts