Handmade with Japanese Soybeans, High-quality Artisanal Natto from Tokyo’s Amakusa Natto Spreads Out Worldwide

High-quality Tanba black soybean natto in a crystal Baccarat glass

8:00 JST, February 11, 2024

Natto made of large black soybeans glistens in a crystal Baccarat glass. Made from the finest black soybeans produced in Tanba, Hyogo Prefecture, the natto spreads a rich taste of soybean in your mouth when eaten.

Artisanal natto maker Amakusa Natto in Mitaka, Tokyo, produces the popular traditional Japanese fermented product entirely by hand, using only the finest domestic soybeans. In other words, it is one of the highest quality natto in Japan. It is relatively less pungent and is not as stringy either. Dry natto, derived from this natto, has attracted the attention of vegan restaurant owners overseas, and orders are coming in from all over the world. I visited the store one day in January to see how natto is made.

When I arrived at 11:00 a.m., soybeans that had been soaking in water were being sorted out in the back of the store. “After removing the soybeans that have not soaked properly, they are rinsed and then steamed in a pressure cooker,” the owner, Hitoshi Sakamoto, explained. Genki Kawagishi, a staff member, put the sorted beans into bags by type and set them in two large steamers.

-

Natto sold in Amakusa Natto shop

-

Shiny black beans are found upon opening the package of Tanba black soybean natto.

-

Delicious with sauce as well

-

Soybeans soaked in water sieved through a colander

-

Putting soybeans in a bag for steaming

Six varieties of soybeans are used here, including Echigo-musume (green soybeans), Osodefuri (large soybeans), Hikarikuro (black soybeans). Black soybeans from Tanba and green Aobata soybeans from Yamagata, known as the “emeralds of the field”, are also currently being specially used. All of them are very expensive domestic soybeans. “These are the Tanba black soybeans,” Sakamoto showed me, holding in his palm a handful of the beans from a 25-kilogram bag. The Tanba black soybeans, which are especially expensive, are classified into four grades: they use only the highest grade, called Tobikiri.

-

Various soybeans ready for steaming

-

Soybeans in a pressure steamer

-

High quality soybeans from all over Japan, purchased in 25 kg bags

-

Tobikiri-grade Tanba black soybeans

“Good soybeans are big and above all, have potential as soybeans,” Sakamoto said, taking out a Tanba black soybean natto from the refrigerator. The big, shiny black natto beans look totally different from ordinary natto found in supermarkets. Sakamoto put them in a crystal Baccarat glass and offered them to me. I poked a bean with a toothpick and lifted it up; it was indeed nearly stringless. The natto had such a good aroma and flavor that I was impressed that soybeans could taste this good. The natto smell was minimal so the taste of soybeans was more recognizable and was also delicious with salt or sauce.

Dry natto worldwide

-

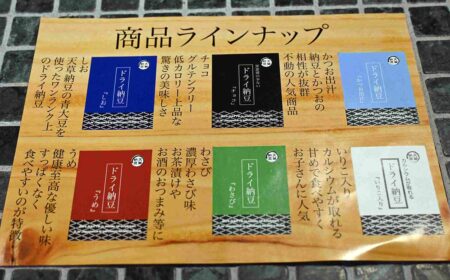

Six kinds of dry natto sold at the shop

-

(From left) Salty dry natto, dry natto with small, dried iriko fish, chocolate-coated dry natto

-

Dry natto product description

“Dry natto is now exported to the U.S., Canada, Mexico, France, Vietnam, Bulgaria, Malaysia, and Hong Kong,” says Sakamoto. Local sales have also begun in Mexico and Paris. Because it is made from good soybeans, it tastes great even processed. While ordinary natto cannot be exported due to its short shelf life and other reasons, dry natto lasts longer and can be shipped overseas.

Last year, Sakamoto launched six different flavors including salt, wasabi, and chocolate coating and increased inquiries from those who found out about them via YouTube and Instagram led to his company’s overseas market rapidly expanding.

Mariana Blanco, who runs the vegan restaurant Los Loosers in Mexico City, visited Amakusa Natto when she came to Japan last December and liked it so much, she participated in a natto cooking event held at a restaurant in Kugayama, Tokyo that same month. Blanco currently stays in France, where she serves special dishes using Amakusa Natto products at her acquaintance’s Paris restaurant HOY.

-

Corned beef natto bowl with corned beef, egg, green onion and small bean natto on rice. (Courtesy of Amakusa Natto)

-

Mascarpone cheese and black soybean natto. (Courtesy of Amakusa Natto)

-

Udon dipping noodles. The broth for dipping the noodles is seafood-based with large bean natto. (Courtesy of Amakusa Natto)

-

Avocado and black soybean Natto. (Courtesy of Amakusa Natto)

Amakusa Natto’s production of dry natto is currently outsourced to another firm, but Sakamoto plans to build a factory for in-house production in the future. He also plans to share recipes for dishes using dry natto on social media.

Wrapped for fermentation

-

Freshly steamed black soybeans on a tray

-

Steam rises from soybeans in an opened pressure steamer

-

Chieko Fujino pours water containing Bacillus subtilis natto culture over steamed soybeans

-

Bottle of Bacillus subtilis natto bacterium

-

Chieko Fujino folding kyogi wood bark sheets

The soybeans had finished steaming while interviewing Sakamoto and moved to the process of wrapping them in kyogi, a thin, sheet-like bark of red pine. Steam rose from the soybeans as they were taken out of the pressure cooker and placed on a silver tray. Chieko Fujino, another employee, sprays in-house Bacillus subtilis natto culture over the beans, then places them on the kyogi, folding it into triangles. The kyogi, ordered from Tochigi Prefecture, are soaked in hot water beforehand to kick-start the fermentation process. The bark reduces the odor of the natto while transferring a subtle aroma of wood. It also has sterilizing properties, which slightly extends shelf life.

-

Kyogi wood bark sheets with neatly aligned corners

-

Soybeans placed in kyogi before the fermentation process.

-

Genki Kawagishi, left, and Chieko Fujino put steamed soybeans in kyogi and fold them into triangles.

-

Soybeans wrapped in kyogi, arranged in a wooden tray ready for fermentation

-

Beans neatly arranged on wooden trays for fermentation

-

“Muro” fermentation chamber

“The corners must be properly aligned to make a nice triangle,” explained Fujino. “The thickness of the kyogi also varies slightly depending on the time of year, so the warming time varies accordingly.” It appears simple but is an intensive and nerve-wracking task.

After wrapping is complete, they are finally set in a fermentation chamber called a muro. Binchotan charcoal is burned on shichirin stoves to keep the temperature inside the chamber at 40 degrees Celsius for 17 hours to ferment. Binchotan charcoal has a deodorizing effect, so the smell of natto is minimized here as well.

Natto goes viral

-

Hitoshi Sakamoto chats with a customer purchasing natto.

-

“I want to spread natto to the world,” says Hitoshi Sakamoto, the owner of Amakusa Natto.

-

Shelves are decorated with various products and autographs of famous people who have visited Amakusa Natto.

It was in March 2020 when 48-year-old Kyoto native Sakamoto began running Amakusa Natto. Sakamoto was a member of a rock band when he was young and later joined a real estate investment company in Kyoto at age 27. After working for about 15 years with the real estate firm, he established his own company and it was around that time, he stumbled on Amakusa Natto on a merger and acquisition website. A Mitaka man opened the business in May 2019 under the name Amakusa Natto as he was from the eponymous region of Kyushu but closed the same year and put the business up for sale online.

COVID-19 was just beginning to spread by the time Sakamoto acquired and began running the business. A state of emergency was declared in Japan: people disappeared from the streets as they were asked to stay home, and restaurants were also asked to close. Fortunately, however, natto, a nutritious and healthy food, was selling well throughout the country during the pandemic as it is said to boost the immune system. Furthermore, Amakusa Natto became recognized both in Japan and abroad when it was featured in a video by famous YouTuber Paolo fromTOKYO, now viewed 3.45 million times. Sakamoto also received a lot of media coverage including TV and magazine features.

Thanks in part to the worldwide recognition, a Lithuanian man who visited Japan last October trained at Amakusa Natto for about a week and is now preparing to make and sell natto in his home country. He plans to start a business in partnership with Amakusa Natto in the future.

Sakamoto said, “We want to focus on overseas expansion with dry natto as our main product and hope to be able to manufacture natto in various countries in the future.”

Amakusa Natto

2-20-12 Nozaki, Mitaka, Tokyo. The shop is open from 11:00 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., year-round. For more information, visit the store’s Instagram (@amakusanattodiary). For inquiries in English, go to the following link:

https://easytobuy.net/inquiry/en/index.php?k=n-f86f17c82b028112

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (2/20-2/26)

-

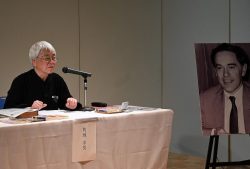

“The Tale of Genji” Back-Translation Project Led to Touching Encounter with Keene; Poet Sisters Recount Memories of Scholar at Packed Talk Event in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (2/13-2/19)

-

Donald Keene’s Drinking Buddy and Translator Yukio Kakuchi Pays Tribute to Japanologist’s Lifelong Work

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages Caused by Fraudulent Actions Without Waiting for Third-Party Committee Review