Translator Fondly Recalls His Drinking Pal, Donald Keene; Writing Piece on Scholar’s ‘History of Japanese Literature’

Translator Yukio Kakuchi stands in the Kyu-Furukawa Gardens, which Donald Keene often visited, in Kita Ward, Tokyo, on July 20.

14:54 JST, August 19, 2024

“He was a good friend and drinking companion, a teacher who taught me how to translate, and a benefactor who always offered me work,” said translator Yukio Kakuchi, 75, fondly remembering the late scholar Donald Keene.

Their relationship, which lasted nearly half a century, from 1972 until Keene’s death in 2019, began with many drinks, and later become a working relationship with Kakuchi translating works by Keene such as “Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912.” I recently visited Kakuchi, who is working on a manuscript titled “What is Donald Keene’s ‘History of Japanese Literature?’”

“No one has done anything on Keene’s history of Japanese literature,” said Kakuchi. In the living room of his apartment in Tokyo, his words were impassioned. The elegant apartment, more than 40 years old, was equipped with central heating and cooling, a rarity at the time it was built. But Kakuchi, a smoker, always keeps the windows open and doesn’t use the air conditioning much, and there’s a nice breeze from outside.

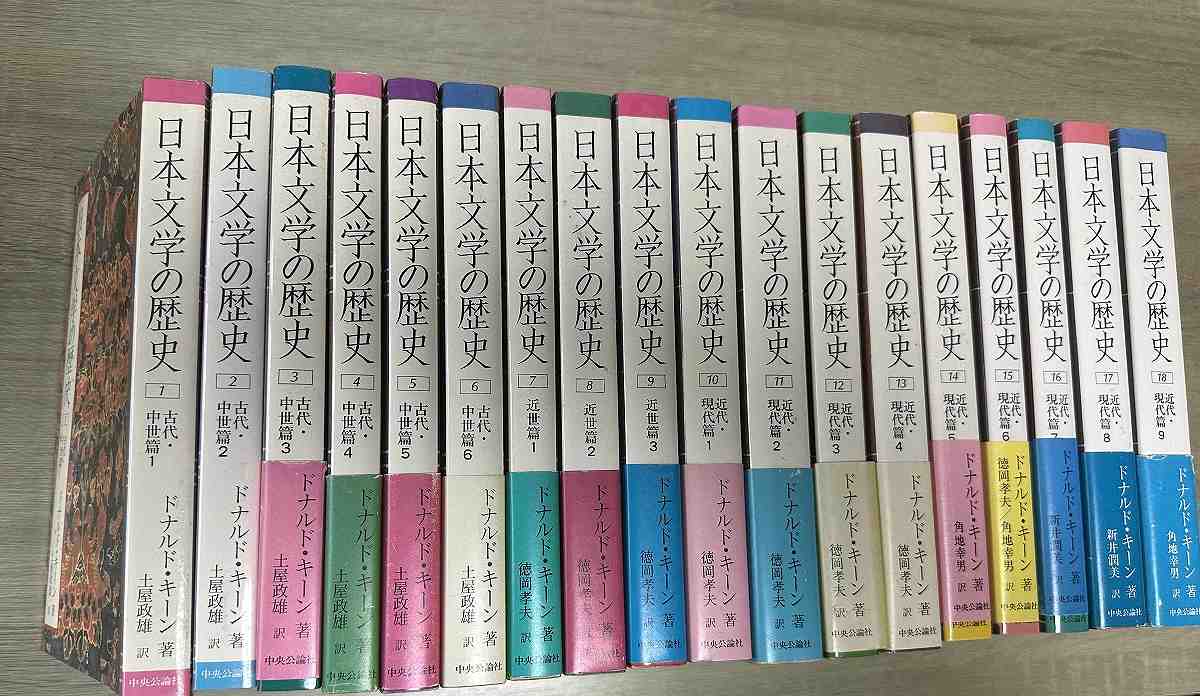

“A History of Japanese Literature,” which Keene spent a quarter of a century writing, is his masterpiece. Japanese version consists of 18 volumes and is divided into three periods: “Seeds in the Heart: Japanese Literature from Earliest Times to the Late Sixteenth Century,” “World Within Walls: Japanese Literature of the Pre-Modern Era, 1600-1867,” and “Dawn to the West: Japanese Literature of the Modern Era.” Kakuchi was also involved in the translation of the “Dawn to the West” section. However, he says the books “have been completely ignored for decades by specialists, such as researchers and scholars of Japanese literature.”

Given the long history of Japanese literature, people generally study the writers and works of one period. Has Keene’s work been ignored because a complete history of Japanese literature by one person is not worthy of respect, or because he is a foreigner? Or, in Japanese way, are specialists showing respect for him by keeping their distance?

Whatever the reason, Kakuchi said that “Keene-san would get very anxious unless he got an immediate reaction to his manuscript, to anything at all. Even though he was so confident in his work, he had that part of him, too. On the other hand, if someone was up front with Keene-san and critiqued him, he would gladly join the debate.”

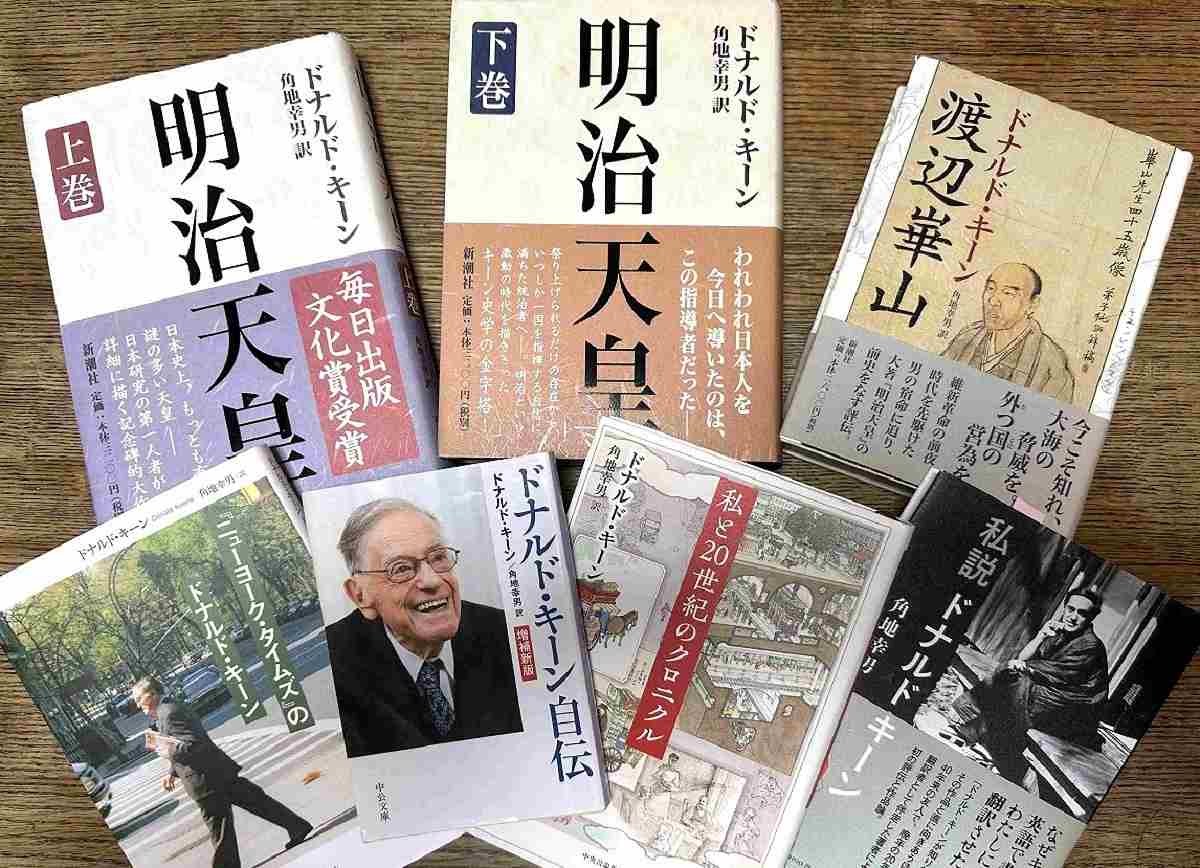

Some of Donald Keene’s works translated by Yukio Kakuchi, and Kakuchi’s own book, lower right

Kakuchi began writing his new work on Keene’s literary history by himself this year, and described his thinking as “Let’s see if it is interesting or boring by actually reading the piece.”

Kakuchi says that Keene’s “A History of Japanese Literature” is, to put it simply, “fun to read.” That’s because, though a “literary history” might sound boring, this is the product of Donald Keene, who reviewed and analyzed each literary work carefully.

The manuscript quotes Takao Tokuoka, who also translated some of Keene’s work before Kakuchi, saying that “[Keene] writes about the actual works, whether they are good or bad, and what is good about them.” This, Kakuchi explains, is what sets Keene apart from Japanese scholars of literary history, who focus on the social and literary significance of a work and rarely refer to the works themselves.

Kakuchi cites as an example Natsume Soseki’s “Meian” (Light and dark) and “Michikusa” (“Grass on the Wayside”), which Keene said he disliked. Quoting Keene’s original text, Kakuchi explains that Keene evaluated the works by focusing on the quality of their writing to determine why he disliked them, rather than simply stating whether he liked or disliked them. Kakuchi also mentions that Keene had read all of Soseki’s works and had high praise all his other writing.

Keene himself wrote of his history, “I think that a literary history with a consistent literary or life view (written by one person) is probably easier to read.” Kakuchi hopes that by publishing his manuscript, he can help people understand the appeal of Keene’s literary history and introduce people to his works.

Donald Keene’s “A History of Japanese Literature”

From drinking to translating

“I just happened to become Keene-san’s drinking friend, and I just happened to start translating his works. It was a series of coincidences,” said Kakuchi.

Their first meeting was in 1972. Kakuchi interviewed Keene as a reporter for what was then called The Student Times, a weekly paper published by The Japan Times. Kakuchi was 24 years old and Keene was 50. Kakuchi was very nervous because Keene was already a prominent figure who had helped introduce the world to Japanese literature. However, he recalls, “When I met him, he seemed young, like a friend who was just a little older than me, and my nervousness disappeared in no time.” However, Kakuchi said that he always felt some sense of tension until the day Keene died, thinking to himself, “I’m drinking with and talking to an incredible person.”

The interview was conducted in Japanese, and Kakuchi wrote the article in English. Keene always spoke Japanese, never English, when talking to Japanese people. Even if the other party spoke in English, he pushed through in Japanese. He took pride in himself as a scholar of Japanese literature.

Keene began inviting Kakuchi to dinner at his home almost every week as a break from his own work.

“His best friend, Yukio Mishima, had already passed away, and his other friends, including Kobo Abe, were busy, so I had the good fortune of being treated to a home-cooked meal and drinking party because I had time on my hands,” Kakuchi recalled.

“The dishes prepared by Keene-san were placed on the dining table, and baguettes were warmed in the oven. The cheese had been taken out of the refrigerator ahead of time and was soft and ready to eat. All I had to do was eat good food, drink wine, laugh and be a good listener. More than discussing literature, we talked about opera, the personalities of close literary friends, behind-the-scenes stories, and travel experiences.”

One day, after some 15 years as drinking buddies, Keene suddenly asked, “Would you translate my works for me?” He said that Tokuoka, who had previously translated him, was no longer able to continue, and a new translator had to be found. Kakuchi, who had no translation experience, refused, saying, “That’s nothing to kid about.” But then Keene looked Kakuchi squarely in the eye and said, “Kakuchi-san, you can do it.” The strength of Keene’s look won out, and Kakuchi decided to start translating.

Kakuchi has since translated more than a dozen of Keene’s later works, including “Frog in the Well: Portraits of Japan by Watanabe Kazan, 1793-1841,” and “The Winter Sun Shines In: A Life of Masaoka Shiki,” and has written his own book, “Shisetsu Donald Keene.” Recently he translated Keene’s unpublished manuscript “Japan after Thirty-seven Years,” which I covered in The Yomiuri Shimbun and The Japan News in February. His translation will appear in the October issue of the monthly literary magazine Shincho, which will go on sale in September.

Keene would often jokingly ask if he was getting the recognition he deserved. When Kakuchi replied, “Even Stendhal wasn’t recognized for 100 years,” Keene laughed merrily.

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Tokyo University of the Arts Now Offering Free Guided Tour of New Storage Building, Completed in 2024

-

Exhibition Shows Keene’s Interactions with Showa-Era Writers in Tokyo, Features Newspaper Columns, Related Materials

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (1/30-2/5)

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

Prevent Accidents When Removing Snow from Roofs; Always Use Proper Gear and Follow Safety Precautions

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan