Steve Kornacki began his journalism career in local New Jersey political reporting, which led to a writing job at the New York Observer, then an editing stint at Salon

17:15 JST, November 2, 2022

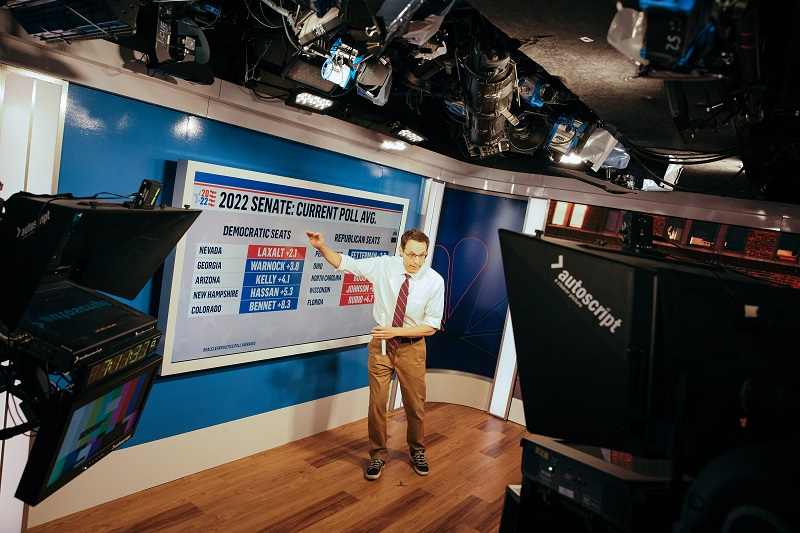

The data is coming in, and the returns are not looking good for Democrats. I’m at one of MSNBC’s studios in 30 Rockefeller Plaza, watching TV star Steve Kornacki run a real-time simulation for the upcoming midterms. This is the first of about a dozen run-throughs representing what network statisticians believe are conceivable outcomes of the 2022 election. In each iteration, batches of votes are meted out approximately as they would be while the polls close. This information is displayed on what MSNBC calls the “Big Board,” an enormous data visualization touch screen that allows Kornacki to interactively check on a deluge of data: what percentage of votes are in, how partisan percentages compare with previous elections, how many seats each party has lost and picked up.

In this fictional future, even early in the “night” – which on Sept. 29 is happening at 9:10 a.m. – it’s looking like a red wave for Republicans. Florida is releasing its first batch of results, and Pasco County and its retiree-filled Tampa exurbs are overperforming Donald Trump’s 2020 trouncing of Joe Biden – a bellwether for the forthcoming Midwestern ballot count. If this trend continues, Democrats will have a painful evening.

As his longtime producer Adam Noboa stands by, murmuring figures to him, Kornacki is feverishly hopping around the Big Board gleaning potential narratives – like the three largely Hispanic counties in southern Texas that have grown increasingly Republican, belying the 2012 “autopsy” the GOP conducted that said the party would have to become more progressive on immigration to win the Latino vote. “Then along comes Trump, and Trump is literally the living, breathing refutation of the autopsy,” Kornacki tells me over lunch that afternoon. “He introduced … not introduced, exacerbated a class element to our politics that actually created an opening for the Republicans.”

Kornacki is playing out one possible version of Nov. 8 – and, if the past is any indication, not just Election Day itself, but the many subsequent days he is prepared to mostly forgo sleep until the final verdict is reached. “He’s very frenetic,” Marc Greenstein, Big Board creator and senior vice president of design and production at NBC News and MSNBC, says about Kornacki. The Board, with its endless information and mysteries – “What type of vote has been counted so far, what type of vote is left, how is the vote varied by type?” says Kornacki later, relaying the ticker that runs through his head during an election – reflects his wonky mastery of the bedlam of electoral politics.

Kornacki is on a monomaniacal quest for clarity, regarding both the returns and what they mean about the country. Watching him seek answers is so addictive that MSNBC delivers a constant stream of it on election nights: He appears in a square in the corner of the screen even when he is not addressing the camera or doing anything that would traditionally appeal to an audience, such as “not texting.”

“We were doing one of the congressional primaries, and it was the first time we all felt like – I personally felt like – we can’t take Steve off the screen,” Greenstein says of the 2018 election coverage. “And I remember kind of middle of the show, we changed our strategy and we basically put … the little box of Steve in the corner of the broadcast – the ‘Kornacki cam,’ essentially, before we formally had it. And it was just because it was so riveting just to see what he was doing, to see him trying to search for new data, to search for those storylines.”

Kornacki has inspired a chastely titillated following that found him in the pages of People’s “Sexiest Man Alive” issue and led to many tweets and online stories calling him “Map Daddy” and referencing his khakis. “It makes me feel a little uncomfortable,” Kornacki says, with much less ease than he projects as he illegibly scribbles on the Big Board.

His improbable turn as a sex symbol is no less likely than him being on on our screens at all. A few weeks after I meet Kornacki, MSNBC President Rashida Jones tells me he’s an “unassuming TV star” who is “the same person whether the red light is on or not.” I certainly see no difference between the person I’ve been watching on television and the one sitting across from me eating salmon, rhapsodizing in spectacularly granular detail about ancient elections. Like Sherlock Holmes not knowing the Earth revolves around the sun because it won’t help him solve cases, Kornacki seems to exclusively retain information that pertains to Kornackian pursuits: He admits he doesn’t quite know what caviar is, and he has never heard of “Euphoria,” HBO’s Emmy Award-winning hit show. (“Is it supposed to be depressing?” he asks when I tell him the general idea: very hot adult actors playing high-schoolers who make compounding bad decisions. “It sounds terrible.”)

While I enjoy Kornacki’s presence on-screen, I don’t know that I’d necessarily meet him and think, That man should be on television. When I tell Jones that, she laughs. “Yeah,” she says. “I think what’s broken through for him is the passion.” When Kornacki is frantically searching for information, Jones says, the viewer understands that “if Steve prioritizes this, then I should be paying attention. If Steve is zeroing on this, it must mean something.”

The man is a beacon for those who turn on MSNBC on election night to find out who will lead the country. How many people clung to Kornacki’s presence on Nov. 8, 2016, as he explained the dwindling number of increasingly byzantine paths to a Clinton victory? How nice was it in 2020 to know that Kornacki was conscious for the days before the election was called, sucking down Diet Cokes and waiting to analyze the outstanding ballots that would determine the next president of the United States of America?

And yet there’s an irony to the Kornacki phenomenon. Viewers look to him for answers, but Kornacki himself understands better than most the fragility of certainty. Perhaps it’s because he covers politics almost as a sport: “People use ‘horse race’ as a disparaging term,” he says. “But I’ll defend horse-race journalism … or at least the idea that there can be useful horse-race journalism.” He knows that on Election Day, anything can happen – that the factors separating a win from a loss can be highly unpredictable. “Where a lot of people have confidence, I have doubts,” he told me in October, a month before the big day. “My doubt-to-confidence ratio is extremely high.”

***

The beauty of data journalism, in theory, lies in the solidity of numbers. “You can talk about something, but when you can put a number on it, you can compare it to something and then you can really understand it,” Kornacki says. “That was a huge thing for me growing up. Every day I was going out to get the newspaper, open up the sports section; you check the standings, you check the scores.”

When he was in sixth grade in 1990, Kornacki portrayed then-Massachusetts gubernatorial candidate John Silber in a mock election in his Groton middle school and was delighted to see the process unfold locally: There were debates and ads and, finally, voting day, and he didn’t know how any of it would turn out until he sat down with his father, a corporate recruiter, and watched the returns tally up starting at 8 p.m.

Kornacki began his journalism career in local New Jersey political reporting, which led to a writing job at the New York Observer, then an editing stint at Salon. (Though his conversations are signposted with the years of campaigns and sporting events, Kornacki seems to be aware of the significant dates of own life and career only if they coincide with moments of historical importance.) He has avoided making political predictions since 2010, before he fully crossed the Rubicon from written word to television. That year, Republican legislator Scott Brown was running in a special election to fill one of Massachusetts’s U.S. Senate seats. “I remember there started to be a little bit of buzz that Brown might have some momentum,” Kornacki recalls. “I was emphatic that he’s not winning this race” – which he wrote in a Salon column at the time. ” ‘Here’s all the reasons. I’m from Massachusetts. Trust me.’ I couldn’t have been more arrogant, and obviously I couldn’t have been more wrong.”

By 2016, Kornacki was working full time for MSNBC. Like everyone traumatized by the dissonance between the prognostications around that Election Day and what actually happened, Kornacki understands “uncertainty is increasingly part of our elections.” “There’s also a healthy dose of skepticism toward any kind of consensus that emerges,” he says. “Because so often it’s just missing variables. It doesn’t anticipate reactions to reactions to reactions” – like the fact that some of the people who cast a ballot for Trump in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Michigan and Ohio were, Kornacki says, “just hostile to the media, hostile to the pollsters that are part of the media and are just not reachable by anything that’s done by polling.”

His instinct toward caution in predicting the path of chaos was reinforced by the research he conducted for his 2018 book, “The Red and the Blue: The 1990s and the Birth of Political Tribalism.” Availing himself of NBC’s vast archival news resources, Kornacki found himself deeply drawn in by what might have been. “I swear I feel like I’ve put myself back living in that moment in my head,” he says about reading old newspaper clippings covering elections he knows the outcomes to. “I feel like I’m there.”

“The present day, where I genuinely don’t know what’s going to happen in November,” Kornacki says, “I could give you five different scenarios right now and we could talk about all the different possibilities. I like going back and being able to feel that same sense. … Reading about the 1976 election or something and immersing myself in the kind of real-time coverage of it and actually getting to the point where I feel like there’s 20 different ways this can go. … You start imagining like, ‘Jeez, what if this other thing had happened? What ripple effect could that have set off? How different would the world be today?’ “

***

Steve Kornacki in his office at MSNBC’s studios.

Kornacki’s job, as he sees it, is “to perceive what the range of possible outcomes is. You know, looking ahead to November, race by race and just kind of big picture, imagining the different scenarios and trying to understand what ingredients would go into each scenario. Trying to take the metrics that we do have, the poll averages, and trying to discern: Is there some movement here? Does it suggest something?”

Arguably, for him, not knowing is the most interesting part. “I think it intersects with the horse-race thing,” he says. “It’s up to you to figure out what to make of it. But I’m just here to show you.” Kornacki is also a fan of literal horse races; he spent his free time handicapping, attending and betting on them before he began analyzing them for NBC Sports. (Kornacki still places bets, even on horse races he covers; that’s one way, at least, that politics and sports diverge.)

Big Board creator Greenstein says, “We don’t ever sit there and say, you know, ‘Steve, hey, can you tell us who’s going to win Pennsylvania tonight?’ Like, we all kind of know better. That’s not the business we’re in. … We’re always so careful, not only on air but frankly even behind the scenes, not to bank our coverage on, ‘Well, what do you think?’ We want to wait till we see numbers to really talk about where the results are going to end up.”

“We have an incredible team that focuses on predictions on election night,” Jones says. “It’s a room full of data scientists, many of them PhDs. They lock themselves in a room and they use the data and the historics and the qualitative and quantitative information to come to that conclusion. [Steve’s] not in the prediction business. And I think … part of why his credibility is so important and why he’s been able to keep it intact is he really focuses on providing context around the facts, rather than taking the step forward to make predictions.” (Even so, Greenstein has a running joke requesting sports forecasts: “Hey, Steve, can we just figure this out so we could go to Atlantic City and be rich?”)

This Election Day, Kornacki will wake up early and vote at his local precinct in Manhattan’s East Village, where he has lived for many years. Sometimes he thinks about moving – today Duluth, Minn., sounds appealing – but says he gets “paralyzed by indecision very easily. Part of that is just kind of recognizing how the best predictions can go awry.”

Producer Noboa will be with Kornacki, helping him unfurl the results for viewers. Kornacki will collect the numbers, parsing and gaming out their meaning. “What are we uncertain about?” Noboa will ask the person he calls “the channeler of information.” They will drink Diet Cokes and eat little, fueled by the anticipation of the day and the week it might turn into. Viewers, says Greenstein, will see “he’s moving around and how excited he is. … He’s constantly working at that board to find data and to find those storylines … that journey of trying to get to what’s going to happen over the course of the evening that’s more exciting and maybe even … different than what he had personally hoped would happen.”

As in the past, Kornacki will try not to sleep until the moment the decision desk makes the call. Noboa says Kornacki stays awake because he rightly feels ownership over relaying the final results of the data he’s so lovingly and obsessively collected. Kornacki sees it a little differently: “That’s going to be a big moment,” he says. “Like tickets to the Super Bowl stadium in the fourth quarter.”

In the lead-up to that moment, he’s guaranteed to be exuberant about the search for facts – but also relentlessly cautious about what we do and don’t know. I relay to Kornacki my experience of watching him in 2016: “It’s over,” my husband said around 9 p.m. “Steve says it’s not over!” I yelled back as he walked to the bedroom. “The technical answer is our decision desk has a very precise mathematical threshold before they’re going to call a state for the presidency,” Kornacki says when I tell him this. “So we can be in a situation where it’s basically over, and everything your husband is saying about where it’s going is right. But we’re not going to call it on the air until we hit that threshold. In other words, we could be at 98 percent sure that something’s going to happen. We’re not actually putting the check mark on air.”

Which means that in the name of precision and responsible skepticism, it’s often this data journalist’s job to pretend an election is a horse race even when it no longer is. And that may be his real gift to America: to let us spend a few precious, delusional hours on Kornacki’s Board, where any outcome is still possible. Instead of ascending into elation or surrendering to despair, we see the votes coming in, a few thousand from Maricopa County, a few thousand from Erie – and remember that politics is fickle, that nothing is predetermined, that next time really could be different.

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Prudential Life Expected to Face Inspection over Fraud

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan