13:53 JST, March 17, 2021

Climate change is one of the crucial issues that U.S. President Joe Biden has committed to tackle, and the United States may join hands on this with the European Union, which is keen on environmental measures. Keio University Prof. Shumpei Takemori, an expert in international economics, shares his views, saying Japan should not be unconcerned with this move.

The Biden administration is accelerating its actions. The biggest move so far is an unprecedented $1.9 trillion pandemic relief bill equivalent to 9% of U.S. gross domestic product.

As the COVID-19 vaccination program progresses in the country, the U.S. economy is expected to return to pre-pandemic levels by autumn even without the relief plan. Some experts say that such stimulus will cause economic overheating. Some forecast that U.S. GDP will increase by 8% this year.

Economic debate is now focused on whether inflation will occur as the economy overheats. The global rise in long-term interest rates and plunge in stock prices in late February spurred debate.

Holding bonds brings income gain, but high inflation cancels out this gain. Therefore, in an environment where high inflation is expected, bonds become less attractive, and higher interest rates are needed to encourage bond holdings. At this time, stocks — the nature of whose interests are similar to the interests of long-term bonds — also become less attractive, and stock prices fall.

At present, major central banks continue to buy bonds to support the economy, creating low interest rates worldwide. However, they would have no choice but to stop buying bonds when inflation rekindles, and interest rates would rise by doing so. Such market expectations are behind the turmoil in stock prices. The turmoil stemmed from these speculative actions, but in reality, the inflation rate has not risen.

Low-income earners

Prolonged inflation makes business decisions difficult and harms the economy. However, it is general knowledge in economics that such inflation occurs only when workers continue to demand higher wages. As global competition and mechanization advance, the power of trade unions has waned and the pressure for higher wages has weakened in developed countries.

The high unemployment rate amid the pandemic makes the change from low to high inflation unlikely to happen.

Even if there is a temporary rise in prices, the Biden administration will remain proactive. This is because its support base is low-income earners who were hit hard by the pandemic, and they will not keep supporting the administration unless strong policies are taken to support them.

The Biden administration’s nature of taking policies in favor of its support base is evident in its economic diplomacy, too. His administration aims to make a rapid shift from American unilateralism under the era of former U.S. President Donald Trump to multilateralism. Achieving this goal means cooperation with the EU, not with the Trans-Pacific region that includes Japan. In the event of a tie-up with the latter, the United States has to place emphasis on strengthening cooperation with the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement (TPP), which aims at promoting regional free trade. But, support for free trade is currently weak among U.S. Democrats.

Indirect cost

On the other hand, if the United States joins hands with the EU, the key area of cooperation will be the environment, especially decarbonization policies, and the political support for this is strong among U.S. Democrats, especially liberals. This is why the Biden administration’s economic diplomacy is based on cooperation with the EU.

The TPP was intended to lure in China by creating an attractive and huge market, and lead the country to revamp its system. The U.S.-Europe cooperation on global warming is also a move against China, using carbon pricing as a key strategy.

In addition to direct costs arising from the consumption of resources and labor, economic activities generate carbon dioxide, or an indirect cost of causing global warming through the greenhouse effect. Producers normally do not take account of this indirect cost in their economic activities. Carbon pricing is a policy measure that takes this cost into account.

Two typical methods are emissions trading, in which emission allowances are allocated to producers, who have to buy allowances from others if they want to increase their emissions; and a carbon tax, which is levied on producers based on their emissions.

Taxes on emissions

In any case, producers will have to bear the additional costs. But, if countries only ask their domestic producers to bear the cost but not overseas producers, the system works in favor of overseas production, shrinking their domestic industrial base. Therefore, the carbon neutral-oriented EU has been insisting on the necessity of border adjustments by imposing a tax on production abroad, or imports in other words, according to emissions as well.

Since the proposal was made by the EU alone, the system did not become an international rule. But, the new U.S. administration showing signs of staying in line has increased the possibility that border adjustments would become an international rule.

China, the world’s largest CO2 emitter, will be the biggest target of these adjustments. The United States and Europe will be able to use their huge tariffs as tools to demand that China corrects behavior that violates international standards.

Burden on exports

The question is how Japan would respond to this move. It was on Oct. 26 last year when Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga launched Japan’s policy of a carbon neutral society by 2050. Japan is behind in this field.

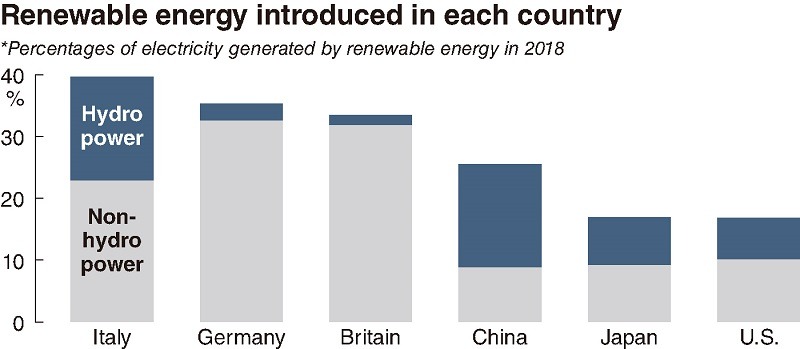

Japan has also been slow at promoting renewable energy, which has remarkably reduced its cost, meaning that the nation’s electricity bill is higher than that in other major countries. If border adjustments were imposed on Japan’s exports based on the EU’s carbon tax rate, Japan would owe a heavy burden. It may be Japan, not China, that will suffer the most from these adjustments.

In the past, Japan got rave reviews for its active industrial policies led by the then International Trade and Industry Ministry, but the policies built back then no longer exist.

It is questionable whether Japan still has any ability and willingness to implement a major and vital industrial policy of imposing a carbon tax on high-emission industries and feed the tax revenue into the development of decarbonization technologies.

Politically, it would be easiest to accept the decarbonization rules pressed by the United States and Europe. But, that would forfeit an opportunity for Japan to make international rules even a little more favorable to its domestic industries. Whether Japan voluntarily participates in the efforts of the United States and Europe and cooperate with them from the rule-making stage will be left to its political ability.

Shumpei Takemori

Professor at Keio University. Studied at Keio and University of Rochester in the United States before taking up his current post in 1997. He has also been serving as a private sector member of the government’s Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy since January 2019. He is 65.

Top Articles in Business

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages Caused by Fraudulent Actions Without Waiting for Third-Party Committee Review

-

Narita Airport, Startup in Japan Demonstrate Machine to Compress Clothes for Tourists to Prevent People from Abandoning Suitcases

-

Japan, U.S. Name 3 Inaugural Investment Projects; Reached Agreement After Considerable Difficulty

-

JR Tokai, Shizuoka Pref. Agree on Water Resources for Maglev Train Construction

-

Toyota Motor Group Firm to Sell Clean Energy Greenhouses for Strawberries

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan