Hiroshima Atomic Bombing Survivor Visits 15 Countries; 93-Year-Old Man Fights to Prevent Future Tragedies

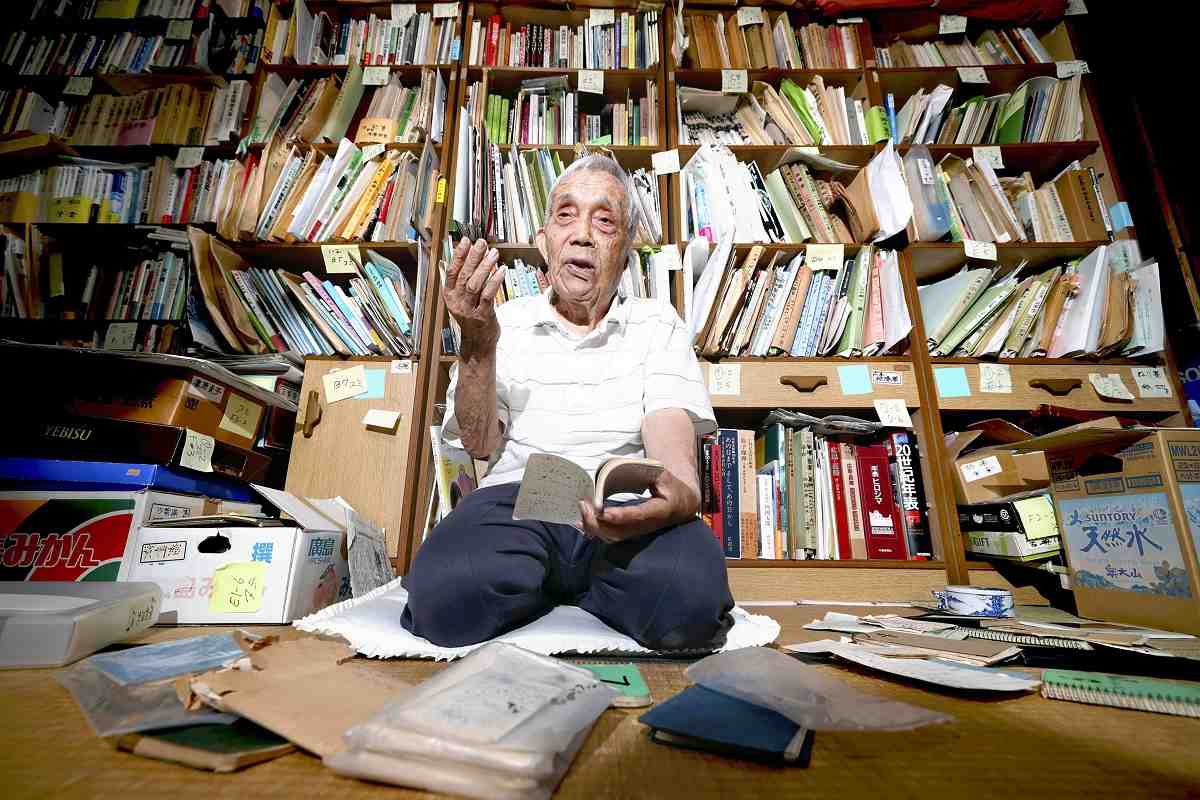

Hiromu Morishita speaks at his home in Hiroshima, with documents and materials related to atomic bombs and peace education behind him.

17:13 JST, August 4, 2024

HIROSHIMA — As the 79th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki approaches, a 93-year-old man who survived the Hiroshima attack at age 14 has been speaking to the world about the cruelty of nuclear weapons.

Hiromu Morishita has visited 15 countries to talk about his experience as a hibakusha A-bomb survivor. He is determined to keep trying to make his voice heard until the last day of his life.

In June, Morishita met in Hiroshima with Charles Oppenheimer, a grandson of physicist Robert Oppenheimer, who is known as the “father of the atomic bomb.”

Charles, 49, works in the United States to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy and the nonproliferation of nuclear weapons. In June, he visited Japan to listen to the stories of hibakusha survivors.

On Aug. 6, 1945, Morishita was lined up near a bridge with other mobilized students. Suddenly there was a flash of light, followed by a loud bang and a blast. When he came to his senses, he realized that his skin had peeled off his face, neck and hands and he was covered in his own blood. As he ran away, he saw the charred body of a baby.

After listening to Morishita through an interpreter for about 30 minutes, Charles said that victims of the atomic bombings have the right to receive an apology.

His attitude made Morishita realize the power of survivors sharing what happened.

“I’m a hibakusha survivor, and he is the grandson of the physicist,” Morishita said. “Our positions are different, but I’m sure we were able to share the understanding that we should aim for a world where nuclear weapons will never be used again.”

Anger and disappointment

After graduating from university, Morishita became a high school teacher in Japanese calligraphy. He did not want to be looked at because of the keloid scars on his face and neck, and sometimes he wanted to run away from his job.

The Fukuryu Maru No. 5 incident of 1954, in which a Japanese fishing boat and its crew were exposed to radiation from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test, gave momentum to the hibakusha peace movement.

Morishita was asked many times to lead the movement. He was told that a person who survived with keloid scars should be at the forefront.

However, he refused such requests and never shared his atomic bomb experience with his students.

Morishita’s first daughter was born in 1963. The sight of his beloved daughter being breastfed by his wife reminded him of the charred body of the baby he saw on the day of the atomic bombing. Morishita thought he should share his experience so that tragedy would never be repeated.

In April 1964, he participated in a world peace pilgrimage in which hibakusha survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki visited 150 cities in eight countries, including the United States and the Soviet Union. During the pilgrimage, Morishita and other participants met with Harry Truman, the former U.S. president who had ordered U.S. forces to drop the atomic bombs on the two Japanese cities.

However, Truman reiterated his view that the atomic bombs were necessary to end the war and did not apologize, disappointing the hopes of the hibakusha survivors. The meeting ended in just three minutes.

“There were no expressions of apology. That was so quick,” Morishita scribbled in a notebook.

“Truman had a child when he decided to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I wonder why he didn’t think of the small children in Hiroshima,” Morishita said. His anger and disappointment became a driving force for him to continue his activities.

Battling on

After returning to Japan, Morishita worked to convey the reality of the atomic bombings through activities such as sharing his experience in and outside Japan. He also served as a guide at the Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima and accepted homestay guests.

In August 2012, Morishita met in Japan with Clifton Truman Daniel, the 67-year-old grandson of Truman. “I wanted your grandfather to apologize,” Morishita said. Daniel looked down and remained silent.

Several years later, Morishita had an opportunity to talk with Daniel again, and he learned that Daniel was engaged in peace activities to spread the experiences of hibakusha across the United States. “It’s more important to spread the importance of peace than to be hostile toward each other,” Morishita thought and vowed not to blame him anymore.

Daniel said he felt that hibakusha survivors were truly worried about the world, human beings and Japan. His hatred and fear of nuclear weapons are now stronger than before.

In April, which marked the 60th anniversary of the 1964 pilgrimage, Morishita visited Oslo at the invitation of Red Cross officials.

Morishita said to an audience of about 200 people: “I want to believe human beings are not stupid. Let’s achieve a world without nuclear weapons.”

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan