The World Peace Giant Kannon is covered with scaffolding in Awaji, Hyogo Prefecture, on Jan. 13.

12:10 JST, January 28, 2022

AWAJI, Hyogo — Work to demolish a giant statue of the Kannon, or goddess of mercy, is underway in Awaji, Hyogo Prefecture. About 100 meters high, the statue is owned by the central government, so taxpayers are footing the nearly ¥900 million bill for its demolition.

Why does the government own this statue? Looking into the background of this matter has shed light on how local governments are struggling to dispose of aging large facilities once owned by private entities.

Ruined facilities

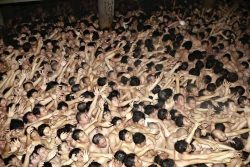

The World Peace Giant Kannon stands on a hillside on Awaji Island overlooking Osaka Bay. Surrounded by scaffolding placed there for demolition, it now looks like a high-rise apartment building. Work is scheduled to get fully underway later this month and be completed around June. The exterior walls will be removed, and the steel frame inside the statue will be cut away, starting from the head, with the severed parts lowered to the ground by a crane.

The statue was built by a local businessman in 1982. It has an observatory deck and stands atop a building that includes a museum, drawing many tourists when it opened. However, the number of visitors gradually decreased, and the founder died in 1988. His wife took over the statue but has since passed away as well. The statue and related facilities were eventually closed in 2006.

After relatives declined to inherit it, the statue continued to deteriorate. The exterior walls are cracked, and some parts have peeled off. The government decided to demolish the statue by nationalizing it in March 2020, based on a Civil Code provision specifying that land and structures that do not have heirs belong to the national treasury.

The demolition cost amounts to about ¥880 million. According to the Finance Ministry, it is highly unusual to spend more than ¥100 million to take down such a structure.

Municipalities reluctant

The responsibility to remove aging structures and facilities lies, first and foremost, with the owners. However, if a building or structure poses a danger to its surrounding area, such as a possible collapse, the local government can forcibly remove it through an administrative subrogation based on the law concerning special measures for vacant houses. The costs are supposed to be recoverable from the owner, but this is difficult to do in reality.

Ruined hotels stand along Kinugawa river in Nikko, Tochigi Prefecture, in July 2019.

The Awaji city government repeatedly asked the family of the statue’s owner to take action. The municipality was initially reluctant to use the administrative subrogation, with an official in charge saying, “We couldn’t specifically consider the matter, due to the backlash expected from residents.”

A similar situation exists with three ruined hotels at the Kinugawa hot spring resort in Nikko, Tochigi Prefecture. The whereabouts of the owners are unknown or the property rights are complicated, and no one currently manages them. The abandoned buildings are a blight on the scenery and there are safety concerns, but the city government has been reluctant to remove them, as demolition would cost about ¥4 billion in total.

A “UFO observation base” on a mountain slope in Biratori, Hokkaido, is also in danger of collapsing. In the 1960s, a leisure company built a pyramid-shaped temple and other facilities that became popular as a tourist attraction. After they were closed down in the 1970s, these facilities were donated to the town, which temporarily used them as a park. However, they have now been abandoned for nearly 20 years.

“We’re supposed to discuss how to reuse the facilities, but even if a decision is made to demolish them, it will be difficult to implement, given the municipality’s financial situation,” a town government official said.

Revitalization

There have been successful cases. In 2020, the city government of Onomichi, Hiroshima Prefecture, demolished a private museum on the north side of JR Onomichi Station that had been shut down in the 1990s. About 27 meters high, the museum was called “Onomichi Castle” for its castle-like design.

The city decided to tear it down due to safety risks, such as decorative ornaments falling down.

An observatory from which visitors can see the Onomichi waterway will be built on the former site of the museum, taking advantage of its location in Senkoji Park, a tourist spot. Of the about ¥200 million spent on the construction, about ¥90 million has been funded with a central government subsidy for regional revitalization projects.

“The government subsidy helped,” a city government official in charge said.

Takero Doi, a professor of public finance at Keio University, expects similar problems to increase.

“The basic premise is that the owners of the structures should remove them. However, local governments should devise methods such as seeking a special tax allocation that’s available at times of disaster and other necessary occasions, by addressing the risk of collapse,” Doi said. “The central government should consider an insurance system in which the public bears the cost of removal, with taxpayer money as a source of funding.”

Top Articles in Society

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

-

Foreign Snowboarder in Serious Condition After Hanging in Midair from Chairlift in Nagano Prefecture

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan