The Beijing High People’s Court, as seen in June

6:00 JST, August 6, 2024

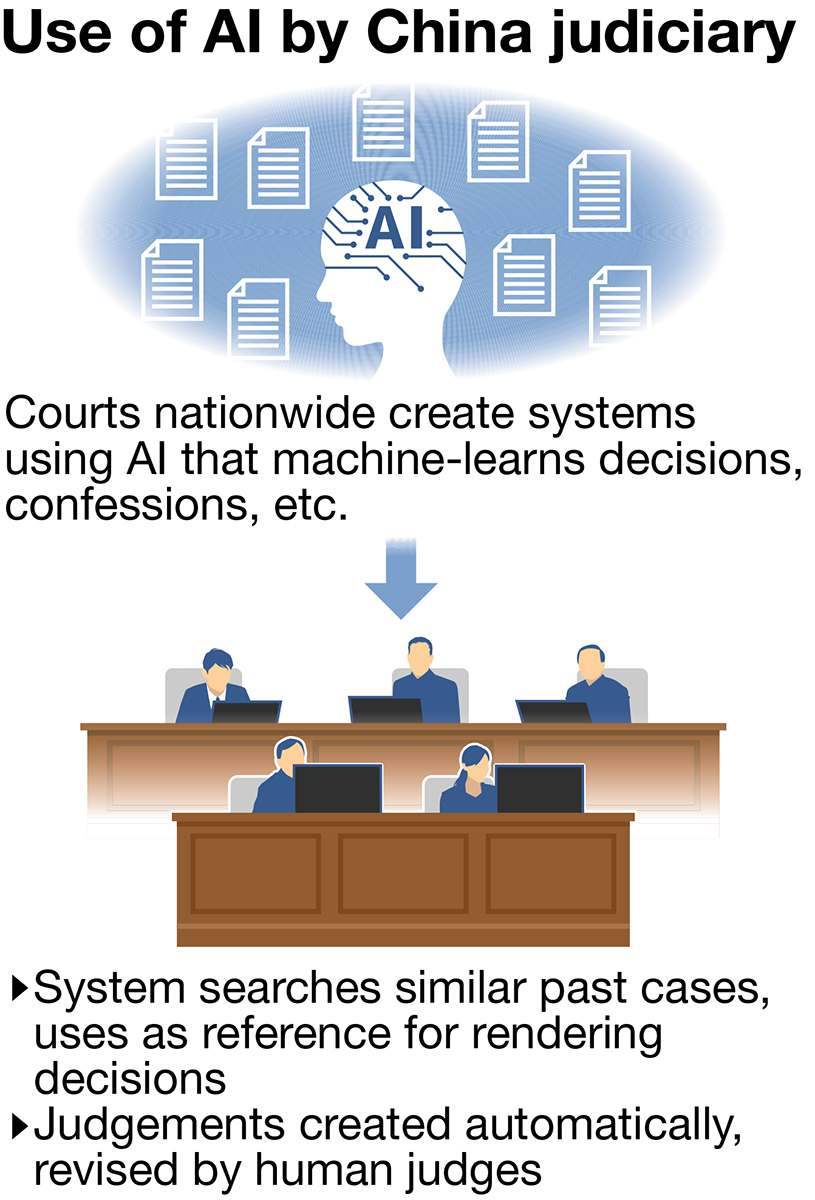

BEIJING — The court clerk enters the details of the complaint in a finance-related civil case into a special system titled “future clerk,” and the judge presses the “create text” button. In seconds, generative AI produces a rough draft of the decision.

The judge makes some revisions, electronically signs the document, and an official electronic version of the judgement is sent to the concerned parties the next day.

Such was the process in the ruling on a case in April at a court in Kunshan, Jiangsu Province, as reported by Chinese media, as China forges ahead with the introduction of artificial intelligence into its judiciary.

The push is raising concerns that under the country’s communist regime, which lacks an independent judicial system, AI learning will be based on biased judicial precedents and could be utilized to facilitate heavy-handed governance.

The Supreme People’s Court, the highest court in China, plans to have all courts nationwide equipped with AI by next year, to be used for preparing the text of decisions and to examine evidence in a courtroom.

A similar system to that in Kunshan was introduced in January in the province’s capital of Suzhou, reducing the time the judges spend reading litigation paperwork by 80%. The time required to process cases is said to have been cut by one-third.

AI systems are being used in criminal cases as well. At a murder trial in a Shanghai court, the chief justice instructed the system to “indicate any discrepancies in investigative materials” and the AI instantly displayed evidentiary items.

The defendant had denied in court ever meeting the victim, but the courtroom screen showed call logs for both over the past two years and a statement in which the defendant told investigators that the two had met. The defendant went silent but in the end admitted that the two were acquainted.

Expedited procedures

The Supreme People’s Court issued an opinion in late 2022 ordering courts nationwide to have AI systems up and running by the end of 2025. While purporting that the systems expedite lawsuits and reduce the burden on judges, the decision was also aimed at fending off public dissatisfaction at the government over a backlog of cases.

Last year, courts nationwide received a combined total of 45.57 million civil and criminal cases, of which 45.27 million were processed. The latter marked an increase of 13.4% from the previous year, indicating that the introduction of AI is having an effect.

With bribery rampant in the Chinese judicial system, the introduction of AI may be intended to narrow the room for bribed judges to hand down distorted decisions. The realization of a “clean judiciary” was among the top court’s stated reasons for introducing AI systems.

Emphasis on ‘fairness’

In China, the judiciary is not independent, and it is unthinkable that an individual judge would issue a decision that is not in line with the Communist Party committee assigned to the court. In the past, human rights lawyers and others critical of the regime have been imprisoned on charges over “inciting subversion of state power.”

A human rights lawyer in Beijing noted with concern that many citizens trust judgments made by AI over human judges, saying “The government is aiming to make people accept conclusions reached by AI that learned from biased precedents by emphasizing that it makes ‘fair judgements.’”

Chinese authorities are able to use big data to analyze citizens’ purchasing habits, interests and preferences.

“In cases where there is little evidence, the use in court of AI analysis of an individual’s past actions could result in the rendering of a judgment that harms their rights,” said Hitotsubashi University Prof. Kazuhiko Yamamoto, a specialist in civil procedure law and the introduction of information technology in judiciary.

***

Japan’s top court opposes using AI in trials

The Supreme Court

The nation’s Supreme Court is positioning itself against the use of generative artificial intelligence at trials. This is because social conflicts of every kind are brought before the court, and there are a thousand different ways to solve them.

“Only human judges can make the final judgments, so it is difficult to imagine generative AI taking over that job,” a senior Supreme Court official said.

“I think it is still totally unacceptable to use generative AI to make court decisions,” said Supreme Court Chief Justice Saburo Tokura at a press conference before Constitution Day on May 3.

He expressed concern that the facts about various AI-related risks, such as copyright infringement due to AI’s collection of vast amounts of data, as well as bias in the material AI systems are trained on, remain unclear.

He also said that it will be extremely important to consider whether using generative AI for the work of judges can win the public’s understanding, taking into account both the merits and demerits of such a move.

Courts handle criminal cases, troubles between individuals and family issues such as those in marital and parent-child relationships, as well as disputes between businesses.

“We sometimes face situations in which unjust outcomes would result if we were to apply the law strictly according to precedent,” a senior judge said. “Generative AI based on past data can only ever provide general answers, so we cannot give it control over the core parts of trials.”

The use of generative AI for administrative procedures outside of trials is being considered, as this is expected to make those tasks quicker and more efficient, but no concrete moves have been made yet.

In an administrative communication issued to high and district courts nationwide in July last year, the Supreme Court said, “In consideration of the latest scientific findings and risks, we must thoroughly study the use of generative AI for judicial tasks.”

Top Articles in Science & Nature

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Space Mission Demonstrates Importance of International Cooperation, Astronaut Kimiya Yui Says

-

Japan to Face Shortfall of 3.39 Million Workers in AI, Robotics in 2040; Clerical Workers Seen to Be in Surplus

-

Record 700 Startups to Gather at SusHi Tech Tokyo in April; Event Will Center on Themes Like Artificial Intelligence and Robotics

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages Caused by Fraudulent Actions Without Waiting for Third-Party Committee Review

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease