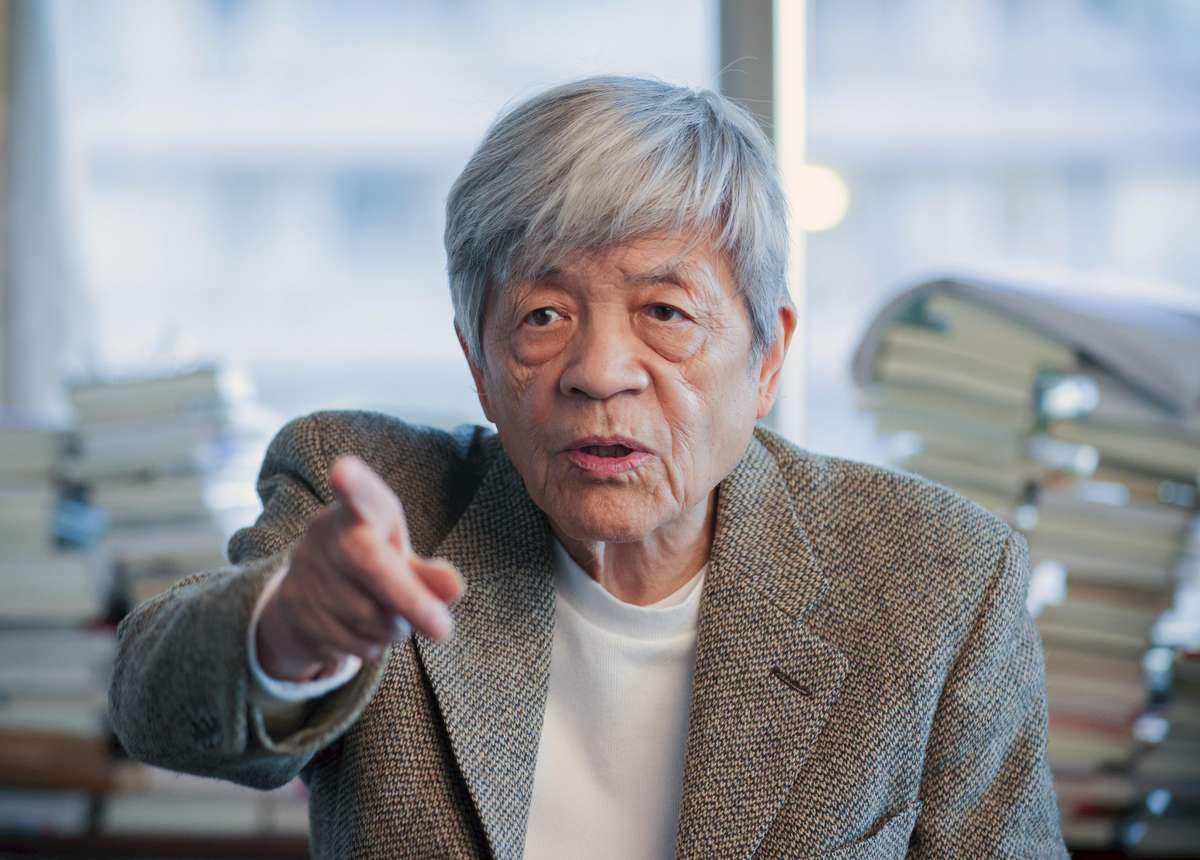

Soichiro Tahara speaks in an interview with The Yomiuri Shimbun in November in Tokyo. “Japanese people are not good at expressing their own opinions,” he said. “They think it’s better to hold their tongue. Since I have quite the inferiority complex, I find it easy. I don’t have any pride.”

11:54 JST, February 27, 2025

Books are piled up everywhere in the room where Soichiro Tahara writes and eats. The clutter seems to express his curiosity, which covers a wide range of fields.

He probes taboos and criticizes authorities. His arguments are sharp and never ambiguous. While he appears self-confident on TV, he said repeatedly in an interview, “There are many things that I have an inferiority complex about.”

Talent as radical TV director

Tahara was born the eldest son of a family that ran a factory in present-day Hikone, Shiga Prefecture. He experienced the end of the war when he was a fifth-grade elementary school student. “The war had been a just war, but it turned into an evil war,” he recalled.

As a boy, he was good at drawing and wanted to become a writer. He entered Waseda University and joined a self-publishing group. “I was told that when people with talent write, it’s called ‘effort,’ but in my case, they told me it’s called ‘wasted effort,’” Tahara said. Writers like Shintaro Ishihara and Kenzaburo Oe made him feel hopeless.

Nevertheless, he felt like he had something to say. He decided to be a journalist but failed all the entrance exams at newspaper companies and broadcasters. After working for Iwanami Eiga Seisakusho (Iwanami Productions), he joined up-and-coming broadcaster Tokyo 12 Channel (now TV Tokyo Corp.) in 1963. However, the broadcaster lacked name recognition.

Tahara turned his inferiority complex to his advantage. He frequently visited the Shinjuku Golden Gai downtown area and other places to meet and listen to various people.

“Since I didn’t have confidence in myself, I asked many questions and told them, ‘I don’t know this or that,’” Tahara said.

Eventually, he developed his talent as an “anarchist and radical” TV director. “Our production budget was small, and we were not very skilled,” he said. “To get people to watch our programs, we had no choice but to produce risky shows that other broadcasters shied away from.”

The broadcaster produced programs featuring a variety of people, including an actor who had his arm amputated due to cancer and Kazuko Shirakawa, a star in Nikkatsu Roman Porno films. Keiko Fuji, a singer at the peak of her popularity, was once asked very directly by a Tokyo 12 reporter of a similar age about her private life. The broadcaster released provocative and radical shows one after another in the 1960s and 70s.

“I wanted to do what nobody else dared do, and I didn’t care if I was killed doing it,” Tahara said. One event in particular proved his words were not an exaggeration: a performance at Waseda University by jazz pianist Yosuke Yamashita. At a time of many student movements, Tahara got Yamashita to perform in front of an audience that included opposing extremist student groups on a piano that had been brought without permission from the university’s Okuma Auditorium.

“I thought the university would report the event to the police and it would definitely provoke a lot of violence,” Tahara recalled. “I thought both Yamashita and I would be killed.”

However, everyone in the audience was captivated by the intense performance. “There was no violence, which disappointed me a bit,” Tahara said.

Around that time, film director Kazuo Hara, working as Tahara’s assistant, closely observed the journalist in action. “I appreciate Tahara because he taught me that documentaries can be interesting.”

Tahara reaches out to interviewees and sets up a scene. “He creates something from nothing. I’m influenced by his method,” Hara said. “He pushed hard on emerging young people to come to the forefront. His persuasion skills were amazing. His depiction of young people directly reflected the times.”

Breaking taboos

Tahara left Tokyo 12 Channel after working there for 13 years and became a freelancer. After he became active as a writer, TV Asahi Corp. started the TV debate program “Asa made nama TV !” (live until morning TV ) in 1987.

The midnight TV program offered opportunities for serious debate and dealt with topics that were viewed as taboos, such as the issue surrounding Emperor Showa and responsibility for the war, nuclear power plants and organized criminal groups.

“Freedom of speech comes down to breaking taboos. Breaking taboos is fun, isn’t it?” Tahara said.

He knew very well about the power of images and TV and took full advantage of them. “This is a live TV program, which makes it more interesting because it shows discussions and even fights among participants as they are,” he said. He brought participants with conflicting positions to the same table to debate while maintaining control.

On “Sunday Project,” a program broadcast by TV Asahi from 1989 to 2010, Tahara engaged in fierce debates with politicians. His method never changed. He continued asking questions and saying, “I don’t get it,” to get the program’s guests to say what they really thought. “I was always honest about asking questions, and that’s why they didn’t hate me. They laid bare the issues for me,” he said.

The content of the program had an impact on politics. It was an honor as a journalist, but “I might have gotten a bit carried away,” Tahara said. “I’m not a dissident. I don’t want to destroy Japan. I want to make the country a better place.”

Love for debate

Tahara truly loves debates. Now he invites guests to a coffee shop near Waseda University and holds an event called “Tahara Cafe” to create opportunities for young people to debate.

His outspoken nature has often caused backlash and criticism. “Blowing up is definitely welcome,” Tahara said. “It’s far better than being ignored. It’s exciting, isn’t it?”

This comment is quite typical of Tahara, who has always spoken his mind and put all of himself into what he does throughout his life. “You only live once, so I want to do all the things I find interesting and anything else I want to do. I’m not satisfied yet,” he said.

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Tokyo University of the Arts Now Offering Free Guided Tour of New Storage Building, Completed in 2024

-

Exhibition Shows Keene’s Interactions with Showa-Era Writers in Tokyo, Features Newspaper Columns, Related Materials

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (1/30-2/5)

-

Prevent Accidents When Removing Snow from Roofs; Always Use Proper Gear and Follow Safety Precautions

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan