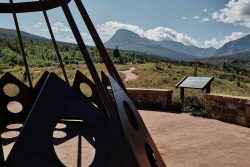

Michael Straight, second from right, stands while wearing his exoskeleton at Gulfstream Park racetrack in Hallandale Beach, Fla.

12:34 JST, October 9, 2024

An exoskeleton gave Michael Straight the ability to walk again after a horse racing accident left him a paraplegic. Over the course of 10 years, Straight walked more than a half-million steps while paralyzed, helping to pioneer a field.

But in June, his machine stopped working, and the manufacturer refused to repair it. For the first time in a decade, Straight couldn’t walk.

“It was like being paralyzed all over again,” he said.

Straight, 38, said he spent three months pleading with exoskeleton manufacturer Lifeward, which last year changed its name from ReWalk Robotics, to replace a tiny component that connected the battery to a watch that controls his exoskeleton. Repeatedly, company employees told him they were no longer doing maintenance on machines more than five years old and then connected him with phone lines where he left voicemail messages that were never returned.

Calling Straight “a real pioneer,” Lifeward CEO Larry Jasinski apologized Friday for the company’s response to the maintenance requests. He said that the company is no longer repairing exoskeletons older than five years because the Food and Drug Administration, which regulates the devices, has approved their usage for that timespan.

But, he added, when he realized that repairing Straight’s exoskeleton was minor and would not have a material impact on the machine’s structure, he overnighted him a replacement watch.

“We didn’t do this one perfectly, and I’m sorry for that,” Jasinski said.

Straight’s path to paralysis started in the 1990s at the Saratoga Race Course, one of the most famous thoroughbred horse racetracks in the country. His grandparents took Straight and his twin brother to the track in Saratoga Springs, N.Y., for the first time when they were about 7 years old, the start of a childhood surrounded by horse racing. The boys were obsessed with becoming jockeys.

“We were around it our whole life, so it’s definitely something we always dreamed about doing,” he said.

In the mid-2000s, Straight and his brother got a chance when they were accepted to the inaugural class of the North American Racing Academy, the first-ever jockey school in the United States. In March 2009, Straight parlayed that training into instant success, riding to a long shot victory at Tampa Bay Downs in his first race.

Then, on Aug. 26, 2009, he was riding I’m No Gentleman at Arlington Park in the Chicago suburbs when tragedy struck. Because of a brain injury, Straight can’t remember anything about the race that paralyzed him. But video shows that Straight’s horse’s front hoofs clipped the back legs of the mount in front of them. The two crashed to the track heads-first.

The accident broke the horse’s neck, forcing authorities to euthanize it. For Straight, the fall caused bleeding on the brain and broke two vertebrae in his upper spine, paralyzing him from the chest down.

Recovery was slow. He says he remembers nothing about the weeks after his accident. But he spent seven weeks in the hospital, which included multiple surgeries. During inpatient rehabilitation, staff had him recite the alphabet and count out numbers to test the severity of his brain injury. They prodded him to build letters into words and words into sentences.

At one point, they strapped him to a bed and lifted it so that Straight was in a vertical position. After a minute, he felt lightheaded and dizzy.

“That was the first time I was like, ‘Wow, this is going to be a long, long road to recovery.’”

But even though he knew it would be hard, Straight said he wanted walking to be part of that road. He asked the first doctor he met at rehab about the chances of walking again. The doctor told him he would be honest with him: 2 percent. As the doctor left, Straight turned to his mom and dad and said, “Two?” Then he turned toward the departing doctor’s back and held up his middle fingers.

“I’ll show him 2 percent,” he remembered saying.

Straight had settled into paralyzed life by 2012 when he was watching a TV show in which a character used a suit to stand and walk. At first, Straight dismissed it as the fictional embellishment of TV writers. But when he followed up with some research, he discovered there were organizations in the nascent stages. One of them was the University of Miami’s Project to Cure Paralysis, which was working with ReWalk Robotics’s exoskeleton.

Straight was instantly sold.

“I wanted it so bad,” he said.

The horse-racing community helped raise the money for the exoskeleton and, in 2014, he moved from Kentucky to South Florida so he could work with the Miami Project to Cure Paralysis. That summer, he was strapped into the exoskeleton for the first time and took his first post-paralysis steps. He was hooked.

But it was one small step in what turned out to be a marathon. Straight spent the next several months working through a checklist of actions he needed to get clearance to use the device at home. They included tests of balance and strength, tasks he repeatedly failed, leading him to get stronger and more skilled.

Finally, in November 2015, he took his exoskeleton home.

For nearly a decade, he has used the exoskeleton two to three times a week, doing about a 1,000 steps per session. Over that time, he has logged more than a half-million steps. Walking in the exoskeleton has provided him with workouts and physical therapy. It helps regulate his bowel and bladder functions and stop his legs from spasming, a common ailment of paraplegics.

“It’s been a game changer,” he said.

Then, in June, the watch he uses to control the machine stopped working, making it useless.

Michael Straight walks using his exoskeleton.

At first, Straight figured it would be an easy fix. He’d had problems with the machine before, ones that were easily solved by ReWalk through over-the-phone instructions or an in-person visit from a technician. This time, however, ReWalk’s employees said they wouldn’t fix the exoskeleton because they were no longer working on machines older than five years.

Straight resorted to Plan B – fixing it himself. But, he told his contact at ReWalk, he just needed him to tell him where he could find the parts. The contact told him to search the internet. Straight went online and discovered the battery he needed. But he couldn’t find the piece that connected the battery to the watch.

Straight said he called ReWalk five times in total and left messages four of those times. He said he called from his wife’s phone another three or four times after that. He never got a response.

So he contacted local TV station WTLV, which published an article about Straight’s struggles. Lifeward responded quickly after that.

Jasinski said that even though Straight’s exoskeleton is working again, he encouraged him to buy one of Lifeward’s newer models. Patients no longer have to foot the entire bill like they did when Straight got his machine, he noted. Earlier this year, Medicare said it would start paying for 80 percent of exoskeletons, which at Lifeward cost about $100,000.

And although that coverage doesn’t extend to paraplegics who have injuries to their spine as high up as Straight, Jasinski said that, given his track record of walking in the exoskeleton, he’s confident Medicare would approve Lifeward’s claim.

“We would take that battle forward,” Jasinski said.

Straight said that his recent experience has left him wary of Lifeward and more prone to look to another company if he decides to buy another device. For now, he said, he’s happy with the machine that’s let him walk a half-million steps more than doctors ever thought he would.

“I’m a paralyzed guy who stands every day, stands or walks every day,” he said. “That’s how I want to put my foot forward.”

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan