Vice-presidential candidate JD Vance delivers remarks during a rally at Middletown High School on July 22.

11:51 JST, October 2, 2024

MIDDLETOWN, Ohio – Ami Vitori was tired of politicians using her home city to illustrate the woes of the Rust Belt even as they neglected it outside of campaign season. So when Ivanka Trump came to town in fall 2016 to promote her father’s presidential bid, Vitori vented in Facebook messages to a friend.

The friend, like Vitori, had been born and raised in Middletown, and professed to share both her commitment to the city and her mistrust of Donald Trump. He told her he was urging campaign officials for Hillary Clinton, the Democratic nominee, to make their own visit to Middletown.

The friend was JD Vance, who had just been catapulted to stardom by his memoir, “Hillbilly Elegy” – and who would soon return to Ohio on what he described as a mission to help forgotten communities like his hometown.

“God help us with the Ivanka visit,” Vance wrote to Vitori in a Facebook message on Oct. 6, 2016, the day the former president’s daughter held an event at a local steel tube supplier. “I’ve encouraged hillary’s people to do something in Middletown,” he said in a follow-up message, adding, “I have told my Republican political friends that if they hadn’t ignored the Middletowns of the world for 30 years we might [not] have Trump to contend with in the first place.”

Vance did not succeed in drawing the Clinton campaign to Middletown, an effort that has not previously been reported. Nevertheless, Vitori and other Middletonians believed that their newly famous native son was taking a renewed interest in the city after 13 years away, a period in which Vance found success in elite circles – first at Yale Law School, then in Silicon Valley.

Their belief was reinforced in early 2017, when Vance published a New York Times column that announced his imminent return to Ohio, described his friendship with Vitori, and declared that people like him should ask “whether the choices we make for ourselves are necessarily the best for our home communities – and for the country.” Middletown’s philanthropists and business leaders soon began seeking to get him involved in civic affairs. Two of the city’s most prominent nonprofits – one of which helped fund Vance’s college education – sought to enlist him in their efforts to support the city’s disadvantaged children.

Yet seven years after Vance’s return to the Midwest, those efforts have not come to fruition. Vitori says she now believes Vance, who is no longer Trump’s antagonist but his running mate, has come to resemble the politicians he once criticized – talking big but doing little to help the Ohio steel city he depicted in his bestseller.

Ami Vitori at her home in neighboring Lebanon, Ohio.

Linda Moorman, who owns a stained-glass store downtown with her husband, at her home in Middletown.

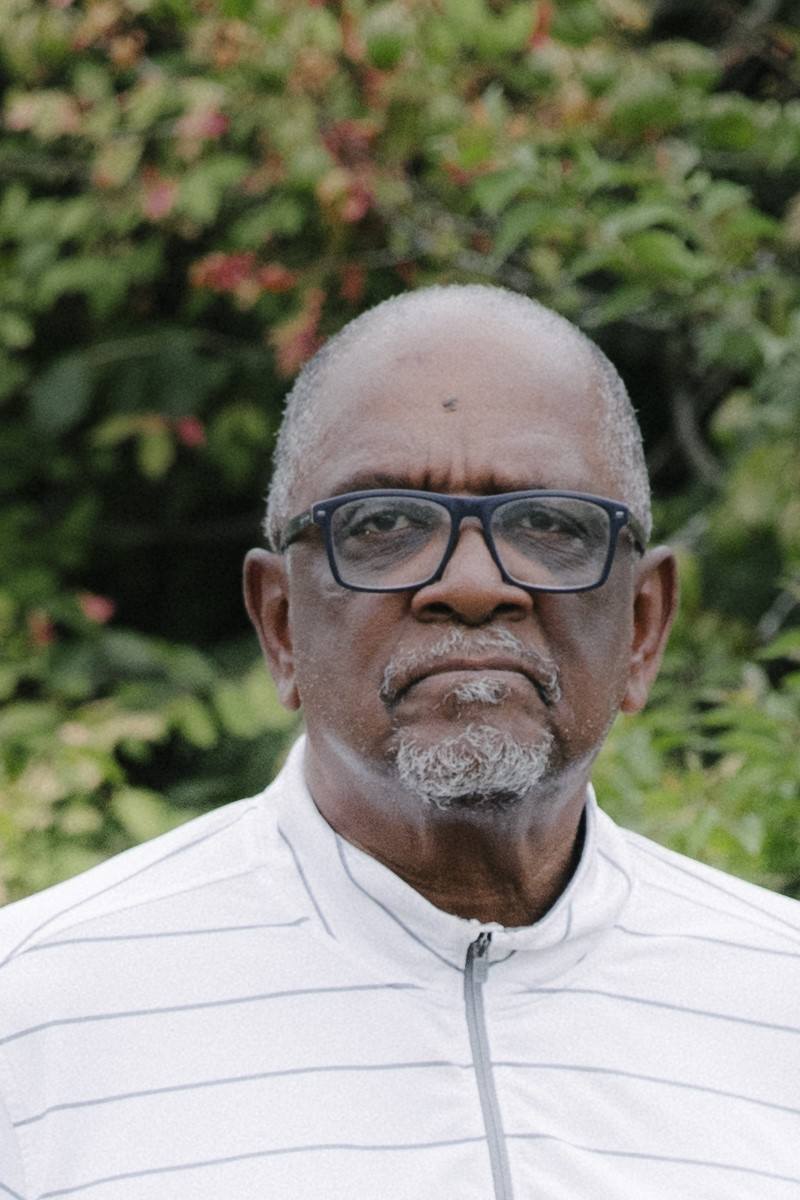

Pastor and former steelworker Michael Bailey stands on former Cleveland-Cliffs land close to his home in Middletown.

“His national profile was traded off the back of Middletown,” said Vitori, who has owned multiple businesses downtown and served on the City Council. “Most people would expect that if you’ve gotten someplace by publicizing your story of a location, maybe that location deserves some continued engagement.”

Interviews with dozens of residents, business owners and civic leaders in Middletown – as well as Vance’s previously undisclosed Facebook messages with Vitori and other private communications reviewed by The Washington Post – illuminate Vance’s fraught relationship in recent years with the southern Ohio city he put on America’s political and cultural map.

Many in town are proud of the 40-year-old vice-presidential nominee, whose name appears beneath Trump’s on yard signs staked across a county that Trump carried by more than 20 points in the last two presidential elections. Some acknowledge and excuse Vance’s absence from Middletown affairs, saying it’s appropriate for him to focus on national issues, particularly over his past 21 months as a first-term senator.

“He’s doing his job. His job is to make this country better,” said Linda Moorman, who owns a stained-glass store downtown with her husband and organizes the town’s annual Santa Parade. “He can’t fix our problems by himself.”

Nevertheless, Moorman added with a wry smile, “I’d love to see him in my parade.”

Others take a dimmer view, saying Vance’s actions show that he regards his hometown more as a political prop than as a community that could use the help of someone with his fame, power and connections. The near-anonymity of his local Senate office – tucked into a corner of a brick building at the edge of town, behind tinted windows and a locked door with no sign – has become an apt symbol to his critics of a national figure whose commitments lie elsewhere.

“I can tell you, I’ve spent my time in the trenches, doing my part to make Middletown better,” said Michael Bailey, a pastor and former steelworker who was once headed the union that represented employees of the city’s storied steel plant. “But he’s never been at the table.”

The Vance campaign did not dispute the authenticity of his private correspondence with Vitori and others. Campaign officials said the senator carefully considers how federal policy will affect his home city.

“Sen. Vance weighs every vote and policy position on how it will affect communities like Middletown, which have been harmed by decisions from Washington for far too long,” Vance spokesman Luke Schroeder said in an emailed statement, saying the vice-presidential nominee “has been and will continue to be a staunch opponent of policies that harm American workers and families.”

Vance is also busily promoting something he now asserts will be good for Middletown: Trump.

Schroeder said the former president’s agenda, including boosting U.S. manufacturing jobs and supply chains, “cutting taxes for workers, restoring energy dominance and putting an end to illegal mass migration, will deliver much needed relief for residents of Middletown and Americans across the country.”

‘You have a voice’

Downtown Middletown.

Middletown is more than the central backdrop of Vance’s memoir; it is a supporting character, whose story he interwove with the struggles and triumphs of his own family.

He described how his grandparents, “dirt-poor and in love,” migrated from Appalachia two generations earlier, drawn by the promise of the city’s steel industry, “the engine that brought them from the hills of Kentucky into America’s middle class.” As Vance’s mother became addicted to opioids and his family descended into dysfunction, Middletown – in his telling – dwindled to “little more than a relic of American industrial glory” as its steel plant shed jobs and cash-for-gold stores overtook its downtown.

The book’s 2016 publication was greeted rapturously in op-ed pages but ambivalently in Middletown. Some believed Vance delivered a pitch-perfect description of growing up in a family battered by addiction and domestic strife. Others said the memoir drifted into misleading or flatly inaccurate caricatures of a Midwestern factory town and elided important parts of the city’s history, including the labor movement, the experiences of a substantial Black minority and revitalization efforts in the years since he had left. Some residents expressed bewilderment as their suburban city of 50,000, situated roughly halfway between Cincinnati and Dayton, became a poster child for rural decline.

Sam Ashworth, former executive director of the Middletown Historical Society, who worked for 15 years at the city’s steel corporation, said Vance’s description in the book of “an Ohio steel town that has been hemorrhaging jobs and hope for as long as I can remember” is off base. Unlike other Midwestern cities synonymous with industrial decline, Middletown never actually lost its core industry, Ashworth noted.

The closest it came was in 2006, when a bitter labor dispute led to a year-long lockout of unionized steelworkers – a crisis that is never mentioned in “Hillbilly Elegy.” Today, Middletown’s 124-year-old steel factory is owned by Cleveland-Cliffs, the country’s largest producer of flat-rolled steel, and still employs nearly 2,400 people, according to the company – less than a third of its workforce in the early 1980s, but still one of the county’s largest employers.

“When industry and manufacturing really started dying in the Rust Belt, yeah, it was rough,” Ashworth said. “But the steel company survived, and today is thriving.”

The Vance campaign defended the accuracy of Middletown’s portrayal in the candidate’s memoir, noting that other factories – including the paper mills that began operating in the 19th century – have closed.

“There’s no debate that Middletown has struggled over the decades,” Schroeder said. “Sen. Vance has always offered his and his family’s honest perspective of that struggle, and while many share that perspective, some do not. That’s the nature of publishing your life story.”

Vitori, 50, grew up in an affluent section of Middletown and attended the same high school as Vance. After graduating from Georgetown University, she worked as an investment banker in New York, an entertainment executive in Hollywood and a consultant in D.C., but returned with her husband to Middletown in 2015 to raise their family. They bought the old J.C. Penney building downtown, opening a boutique hotel, a restaurant and a yoga studio.

As Vitori tried to lure other businesses and people back downtown, she grew frustrated with what she considered the unfairly negative attention Vance’s memoir was bringing to Middletown. In early October 2016, she was on her way out of a doughnut store with her three young children when she spotted Vance in the parking lot with a film crew from Vice News.

“I stormed over and introduced myself,” she said, telling Vance that if he spent more time in their home city, “he wouldn’t still be talking about Middletown when he goes on the talk shows in the way he is.”

Vance was polite and seemed curious about her perspective, she said. A few days later, angered by a Washington Post article about Middletown Trump supporters that invoked “Hillbilly Elegy,” Vitori confronted Vance again, this time in a Facebook post. She pointed out that while Vance stated in “Hillbilly Elegy” that “Middletown produced zero Ivy League graduates” and “virtually no one will go to college out of state,” she personally knew at least three people from their high school who had gone to Harvard or Brown.

In a comment on her post, Vance said his statement about the Ivies had been intended to refer only to his own graduating class. “I’m sorry if you think that bringing attention to a large segment of the town who lives very tough lives isn’t ‘making a positive difference,’” he wrote.

The next day, Vitori sent him a private message on the social media platform apologizing.

“I personally would like to work with you in creating solutions and spreading hope,” she wrote. “You have a voice and can make an impact. That is a big thing.”

Vance responded with a conciliatory message.

“No need to apologize at all, and I’m sorry if anything I said came off the wrong way,” he said. “I really think we’re on the same side in this whole thing.”

‘Committed citizens’

In February 2017, Vitori invited Vance to the upcoming gala of the Community Building Institute of Middletown, a nonprofit devoted to helping the city’s impoverished families and at-risk kids. Vitori was on the board and thought it was a natural philanthropic fit for Vance, given his expressed interest in helping children rise out of troubled backgrounds.

“I’d love to have you as [a] supporter and would be happy to tell you more, give you a tour and introduce [you] to the amazing change makers running the organization,” she wrote in a Facebook message Feb. 10. “I think you’d really appreciate the work they are doing in the most vulnerable communities in our city.”

“That sounds great. I’d love that,” Vance wrote back the same day. “I’ll be in town in early March.”

Vance did come to Middletown in early March, delivering a public lecture at Miami University’s Middletown campus: “From Middletown to the Bestseller List: The Reality of the American Dream.” However, he did not attend the Community Building Institute gala and told Vitori he did not have time to tour the group’s office, their messages show. Instead, they met for coffee.

A week later, the Times published his column, “Why I’m Moving Home.” Vance devoted a substantial passage to Vitori, describing her as a friend who had returned to Ohio after finding success out of state, as he now planned to do.

“Talking with Ami, I realized that we often frame civic responsibility in terms of government taxes and transfer payments,” Vance wrote. “But this focus can miss something important: that what many communities need most is not just financial support, but talent and energy and committed citizens to build viable businesses and other civic institutions.”

To Vitori, such words signaled that Vance planned to use his newfound celebrity and influence to aid in Middletown’s revitalization. Similar signs were to come: In May, Vance told her he was trying to convince the Shift Commission on Work, Workers and Technology – a project funded by Bloomberg and the liberal think tank New America – to come to Middletown. The same month, he said he would ask around to see whether any investors he knew could aid in downtown’s revitalization by providing a loan to finish construction and open a restaurant in the J.C. Penney building.

The Shift Commission never came to town, and the one investor Vance suggested to Vitori wasn’t interested, according to their messages. Vance, meanwhile, moved to Columbus and started a new nonprofit, called Our Ohio Renewal, to fight the opioid epidemic and to help disadvantaged children.

By 2018, the nonprofit had effectively stopped functioning. (It eventually closed, leading to later recriminations among employees who said it was a vehicle for Vance’s political ambitions; Vance has said the group encountered unforeseen hardship when a senior staff member was diagnosed with cancer.) The same year, Vance and his wife bought a $1.4 million home in Cincinnati, about a 45-minute drive south of Middletown. Their 5,000-square-foot residence was designed by the same architect behind Middletown’s Sorg Mansion, a Gilded Age landmark that belonged to the city’s first multimillionaire.

Vance still had family members in Middletown, and was occasionally seen around the city – especially when Ron Howard, Glenn Close and Amy Adams showed up in 2019 to film the adaptation of “Hillbilly Elegy” in his old neighborhood.

In early 2020, Vitori arranged for Vance to meet with officials from the Middletown Community Foundation – the city’s flagship nonprofit, famous for awarding hundreds of scholarships every year. Vance himself had received $1,250 in 2008 to attend Ohio State University, according to foundation records, and delivered the keynote address at its annual banquet in 2016.

John Kiser, the board’s president at the time, said he tried to enlist Vance for a new committee he was forming.

“I said, ‘We’d love to have you sit in on some of the economic development committee meetings, or even serve on it,’” Kiser recalled. “And he said, ‘Yeah, I’d be interested in doing that.’”

A couple of months later, the foundation’s chief executive, Traci Barnett, emailed Vance to follow up.

“I am happy to facilitate a meeting with some of our community leaders to continue the conversation we started back in January,” Barnett wrote, according to emails viewed by The Post. “You can decide what would be the best use of your time and talent here in Middletown.”

Vance replied: “I am definitely interested in being more involved, though I think it’s a little premature to commit to one particular board. I’d like to learn a bit more about the various organizations and where I might actually be useful.”

At the end of 2020, Vance asked former Google chief executive Eric Schmidt to donate $10,000 to the foundation. (Schmidt made such donations as a thank-you to guests who appeared on his podcast, as Vance recently had.) The money arrived in December 2020, the nonprofit’s records show. Vance also donated signed copies of “Hillbilly Elegy” for a foundation fundraiser, according to his campaign.

Vance never did join the board or its economic development committee. His campaign said he was unable to commit his time because of “family considerations” after his second child was born in 2020.

But six months later, Vance returned to Middletown with big news.

‘He’s not on City Council’

Vance launched his Senate campaign in July 2021 at the same tubing factory where he and Vitori had griped about Ivanka Trump appearing in 2016.

“This town made me who I am,” he said, in a speech that eschewed his past critiques of Trumpism in favor of MAGA red meat, including attacks on illegal immigration and critical race theory.

“I think what we need in Washington is not just leaders who talk about doing things, but have actually done them, and will continue to do them,” he said.

Despite $15 million donated by his former boss, Silicon Valley investor Peter Thiel, Vance trailed his primary opponents in polls until he secured Donald Trump’s coveted endorsement. He went on to win the general election, buoyed by tens of millions spent on his race by a Washington-based political action committee.

Vance devoted much of his attention in the Senate to national culture-war issues, seeking to ban federal mask mandates, eliminate nonbinary gender designations on United States passports and oppose American support for Ukraine. But late last year, he announced he was opening an office in Middletown.

It sits in space previously occupied by an addiction treatment center, the name of which has been crossed out on a mailbox with a marker that was also used to scrawl “Sen. Vance.” The office entrance itself does not have a sign, and was locked when a Post reporter visited on a weekday in August.

“Our office is open,” a man’s voice stated through an intercom, declining to unlock the door or answer questions about how many constituents had visited that day or whether anyone else was present with him.

In a statement, Vance’s Senate office said that its Middletown branch is “one of the highest performing offices” and has resolved hundreds of constituent cases this year. The statement said that although the location is open to constituents, the door is locked as a security measure and “nearly all constituents choose to work with our staff via phone or email for their own convenience.”

The statement added, “The procurement process for office signage has been ongoing for some time.”

Earlier this year, the steel plant that employed Vance’s grandfather was awarded $500 million in federal funds to replace its blast furnace. Company officials said the investment would help them to expand their workforce and decrease production costs, effectively ensuring the industry’s survival in Middletown for at least another generation.

The money came from President Joe Biden’s landmark climate and clean-energy spending bill, which Democrats passed without Republican support when Vice President Kamala Harris cast the tiebreaking vote. Vance has assailed the bill, saying it is “dumb, does nothing for the environment and will make us all poorer.” Trump has vowed, if elected, to block the distribution of unspent funds, a move that could cut off Middletown.

“Sen. Vance obviously wants to see more investment in cities like Middletown, both in Ohio and all across the country,” Vance campaign spokesman William Martin said. However, he said the “vast majority” of the bill was spent on other programs that were part of Harris’s “weak, failed and dangerously liberal agenda.”

Kevin Kash, a Middletown attorney and former member of the Butler County Republican Central Committee whose son was close to Vance in high school, said he disagrees with complaints that Vance hasn’t done enough for his hometown.

“People say, ‘Well, what’s he done for our community?’” Kash said. “He’s not on City Council.”

Kash plans to cast his ballot for the GOP in the upcoming presidential election. He trusts that Vance still has Middletown’s best interests at heart.

“I know he still looks upon this as home,” Kash said.

Vitori, who moved to the neighboring city of Lebanon two years ago after finishing her term on the City Council, lost touch with Vance in the months before he launched his Senate campaign.

“When he came back to Middletown and we would spend time together talking about what was going on, or when we were messaging, I felt like he did genuinely care,” said Vitori, who plans to vote for Harris, the Democratic nominee. “I’m not exactly sure what the missing link is.”

As she watches Vance campaigning today, she said, she wonders whether she was right to take him at his word. She said her former friend “feels like a completely different person. So I can see how perhaps he has that capacity to just kind of say what he needs to say.”

Schroeder said Vance “appreciated his early conversations” and “maintained a friendly relationship with Ms. Vitori but declined to involve himself with her further.”

Vance still talks about Middletown. In his speech accepting the vice-presidential nomination at the Republican National Convention in July, he described growing up in “a place that had been cast aside and forgotten by America’s ruling class in Washington.”

A few days later, when Vance held his first solo campaign rally as Trump’s running mate at Middletown High School, he promised that he would be different.

“Middletown, I love you,” Vance shouted into the microphone as the crowd rose, cheering, around him. “I wouldn’t be here without you. And I will never forget where I came from.”

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan