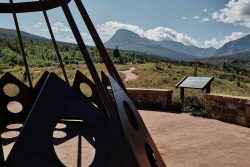

A concrete wall, about 30 feet tall, winds along the Israel-Lebanon border near Shlomi, Israel.

12:25 JST, September 25, 2024

JERUSALEM – Israel has been preparing for its next war against Hezbollah for nearly a decade, and a full-scale conflict has seemed increasingly inevitable with each passing month since Oct. 7. Now, with Hamas diminished in Gaza, Israel is putting its battle plan in motion.

Israel’s punishing airstrikes across southern Lebanon, following last week’s unprecedented attacks on Hezbollah communications devices and a series of strikes on the group’s top commanders, mark a dramatic escalation after more than 11 months of damaging, but calculated, exchanges of fire between the two sides. Now, former officials and analysts say, Israel has opened a window of opportunity for a possible ground invasion, which parts of the security establishment have long advocated for.

“The military has been building and rebuilding the plan for years,” said Miri Eisin, a former senior intelligence officer in the Israeli military who has been briefed on security deliberations. “Every time we got to a place where we were going to do it, there were constraints.”

Now, “it all came together” for the opening phase, she said. “The question is what’s next.”

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was previously reluctant to enter into a full-scale confrontation with Hezbollah, analysts said, fearful of fighting on two fronts and of getting bogged down in another costly and inconclusive war in Lebanon. While those risks remain, there are political advantages to be gained by acting now, observers said: buying more time to rebuild Netanyahu’s dented reputation, delaying a potential post-Oct. 7 commission of inquiry, and shifting public attention away from the grinding war in Gaza and the dire conditions of the country’s remaining hostages.

Israel has demanded that Hezbollah fighters pull back beyond Lebanon’s Litani River so tens of thousands of Israelis can return to the depopulated north. “No country can accept the wanton rocketing of its cities; we can’t accept it either,” Netanyahu said Sunday.

A day after the Hamas-led attacks on southern Israel last fall, Hezbollah turned the northern border area into a combat zone, raining down rockets on residential communities. For nearly a year, more than 67,000 displaced people have stayed with extended family or camped out in hotels. Local leaders, and opposition politicians in Israel, have hammered Netanyahu for not doing more to help them.

“We don’t interest him,” Moshe Davidovich, a regional council head and chairman of the Conflict Zone Forum, which represents displaced residents, complained to Israeli radio last month.

Many Israelis think the country should already have taken more decisive action against Hezbollah, said Yohanan Plesner, president of the Israel Democracy Institute (IDI).

“This is an escalation that was just a matter of time from an Israeli perspective,” Plesner said. “The vast majority of Israelis understand that this situation is unsustainable.”

An IDI poll in August found that 67 percent of Jewish Israelis thought the country should respond more aggressively to Hezbollah’s attacks, with 47 percent supporting “an assault deep into Lebanon that includes striking at its infrastructure.”

The approximately 1,500 targets the Israeli military says it has hit in recent days are part of detailed war scenarios that have been meticulously planned for years, Eisin said. “Hamas did on Oct. 7 what everyone was waiting for Hezbollah to do,” she explained.

Israel’s security chiefs pushed to put the plans into motion just days after Oct. 7, Eisin said, an account corroborated by a senior Western diplomat, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive matters. Then, according to Eisin and the diplomat, it was Netanyahu who stepped back, amid concerns that the military could become overextended.

The prime minister’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

More than 11 months later, the picture has changed significantly. Israeli forces have degraded Hamas’s military capabilities and entrenched their occupation of Gaza, allowing the movement of resources and personnel to the north. Just as important, said Yossi Kuperwasser, former head of the research division in Israel Defense Forces intelligence, Israel believes that Hezbollah and Iran, its main patron, lack the appetite for an all-out war – and that it can continue to up the ante without major repercussions.

“We were the first to escalate, and that was to our advantage,” Kuperwasser said. “We went to a new phase and broke the rules,” he added, referring to the unspoken rules that governed the tit-for-tat border fire since Oct. 7.

The equation started to shift in late July with Israel’s assassination of Fuad Shukr, deputy to Hezbollah secretary general Hasan Nasrallah, in suburban Beirut, beginning what Eisin called a “countdown” to war. Last week’s radio and pager attacks, characterized by some in the Israeli security establishment as a “use it or lose it” moment, probably sped up the timeline, she said.

Prolonging the state of war suits Netanyahu, said Gayil Talshir, a political scientist at Hebrew University, helping to delay, or distract from, domestic threats to his premiership. Israel’s longest-serving leader remains mired in several corruption trials, faces demands from his ultra-Orthodox coalition partners to rescind a controversial military conscription law and, when the war ends, will probably be required to answer to an Oct. 7 commission of inquiry.

“If it remains the way it is now, destroying Hezbollah infrastructure, Netanyahu will have gained some political strength,” Talshir said. “But this is the Middle East, and everything can escalate at any time,” she warned, “and if Nasrallah begins firing thousands of rockets on Tel Aviv, I don’t know if the Israeli public will be forgiving.”

Military ambitions in Lebanon have come back to haunt Israeli leaders. Then-Prime Minister Ehud Olmert launched the last war against Hezbollah in 2006 vowing to “change the equation” on the northern border, but the militant group fought Israeli forces to a standstill, and Olmert soon faced public outcry over Israel’s losses. About 120 IDF soldiers and more than 40 Israeli civilians were killed, in addition to more than 1,100 Lebanese civilians and combatants. After the war, the Winograd Commission found the political and military establishment responsible for “grave failings.”

Since Oct. 7, Kuperwasser said, the Israeli public has accepted that military deaths are inevitable to restore security. Still, he said, “it’s not an easy decision to launch a ground offensive.”

Danny Danon, Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations, said Tuesday that Israel is “not eager” to start a ground invasion and would prefer a diplomatic solution, something the Biden administration, its European allies and Middle Eastern leaders are pushing for.

“As we speak there are important forces trying to come up with ideas, and we are open-minded for that,” Danon told reporters.

While the IDF has repositioned some troops to the north in recent days, it’s unclear if they are preparing to cross the border.

“Hezbollah today is a different organization than it was a week ago,” Defense Minister Yoav Gallant told troops Tuesday. “We have additional strikes already prepared.”

Two days of relentless strikes on Lebanon’s south and east have killed more than 550 people, according to Lebanon’s Health Ministry, which does not distinguish between civilians and combatants but said 54 children, 94 women and nine paramedics were among the dead. In the months prior, more targeted Israeli attacks killed hundreds of Hezbollah members and displaced more than 100,000 people in Lebanon. Yet there is no indication that increased military pressure will force Hezbollah to retreat or allow Israelis to return to their homes in the north.

“A year after the war in Gaza began, we are in a war of attrition, and [Israelis] are very much worried that the same thing will happen but be more intense in Lebanon,” said Michael Milshtein, a former Israeli intelligence official and head of the Palestinian Studies Forum at the Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies.

Netanyahu’s doctrine rests on the assumption that if you use “more and more power the enemy will be more flexible,” he said. “But it didn’t work in Gaza,” and Hezbollah is unlikely to back down either.

Nasrallah has said his group is committed to fighting in solidarity with Palestinians until the war in Gaza ends, leaving open an avenue to resolve both conflicts at once. But Netanyahu has resisted months of pressure from Washington and his own generals to agree to a cease-fire and hostage release deal with Hamas. In June, President Joe Biden said there was “every reason” for people to conclude that Netanyahu was prolonging the war for his own political purposes, though he later walked back the comments.

A cease-fire in Gaza would “almost immediately” cause Hezbollah to hold its fire on northern Israel, said Milshtein. But “Netanyahu doesn’t want an end to the war in Gaza,” he said.

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan