Avigail Elazar rides a Brightline train heading north from Miami.

13:15 JST, August 31, 2023

ORLANDO – Amtrak’s decades-old monopoly on intercity passenger rail travel will fall in the coming weeks when Florida becomes home to the fastest American trains outside the Northeast Corridor.

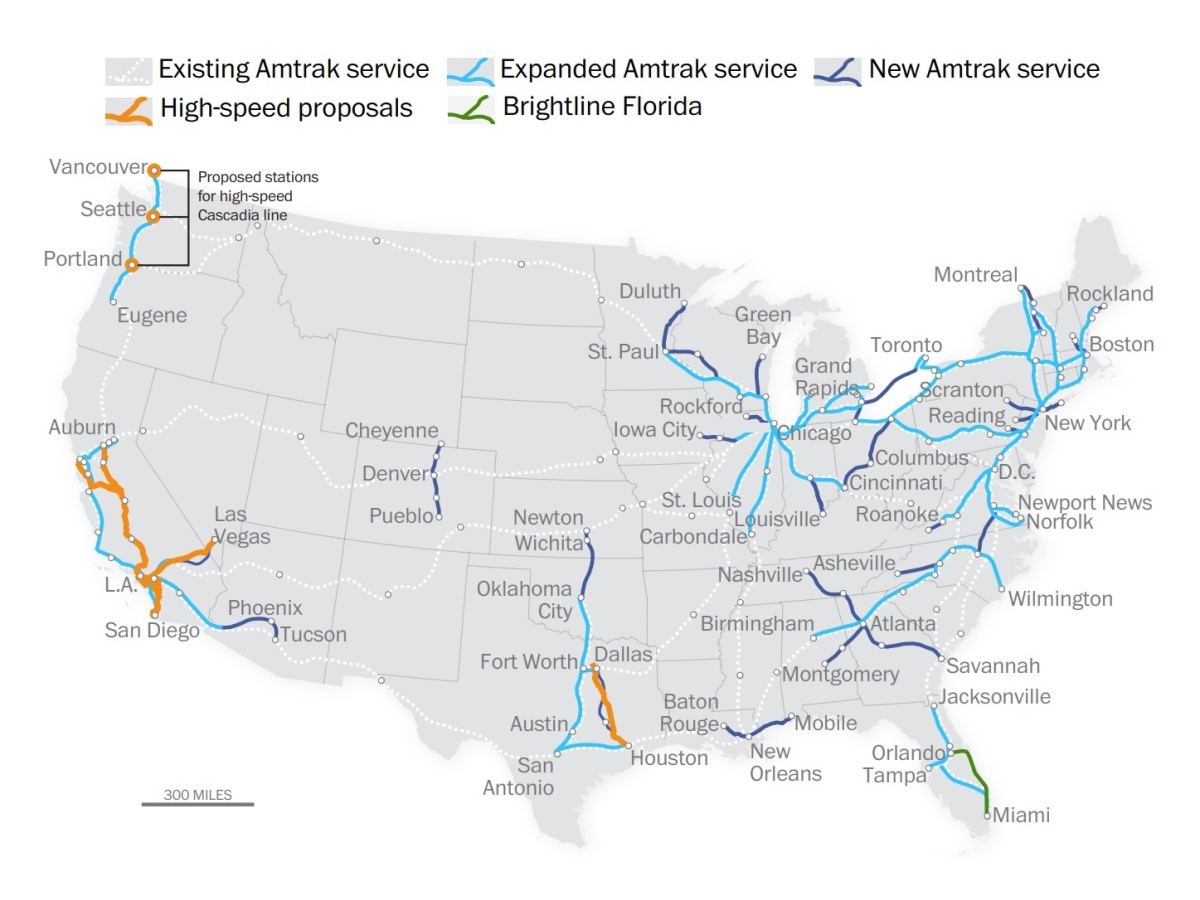

Brightline, the only private passenger railroad in the country, is slated to open its newest station here later this year, providing a train connection between Orlando International Airport and South Florida in three hours. Meanwhile, work is progressing on high-speed projects in Western states and Texas, while Amtrak is eyeing its biggest expansion in 52 years.

Two years after the infrastructure law began pumping $66 billion into the nation’s aging rail network, domestic passenger railroads are showing their greatest signs of strength in generations. Amtrak’s singular grip on transporting U.S. rail passengers is slipping as private companies, states and the federal government look to fast trains as environmentally friendly alternatives to traffic-clogged highways, while developers promise speeds rivaling those in Europe and Asia.

Amtrak says it views other rail providers as complementary to its offerings, coming as the nation’s longtime passenger rail – newly flush with billions of federal dollars – embarks on its own plan to add 39 routes while linking dozens more cities. President Biden, whose fondness for the system earned him the nickname “Amtrak Joe,” is perhaps the bipartisan project’s biggest booster.

Launching with no federal help, the modern debut of private passenger rail connecting two major metropolitan areas will come to fruition when Brightline riders arrive in Orlando from downtown Miami. The Federal Railroad Administration expects to sign off within days, triggering a three-week testing period before Brightline carries passengers. The company will then set its sights on a $12 billion high-speed railway from Las Vegas to Southern California, a massive undertaking that could put trains traveling at 186 mph on America’s tracks by 2028.

“We’re much closer than we’ve ever been. It’s going to happen,” said former transportation secretary Ray LaHood, putting the Western U.S. project at “the top of the list” of major corridors that could place the nation on the high-speed rail map.

The test case for the U.S.’s passenger rail ambitions is taking place in car-dominant South Florida, where a gleaming station has transformed a long-overlooked Miami neighborhood three miles from the southern terminus of Interstate 95.

Amtrak service and high-speed rail proposals

***

After operating much like a commuter service through South Florida, the Orlando station will be the nation’s first non-Amtrak passenger train connection between two metro areas in four decades – a project with nearly $6 billion in private investment. Although not a true high-speed operation, the Brightline Florida service will surpass speeds of 125 mph in some areas – the nation’s fastest train outside the D.C.-Boston region.

Five years after Brightline opened its 67-mile service between Miami and West Palm Beach, passengers fill the five-car trains for sporting events and festivals while commuters use it to get to jobs. Students receive discounted passes for educational excursions.

Brightline uses business tycoon Henry Flagler’s original Miami train station and his Florida East Coast Railway, built in the late 1880s. The station had fallen into disrepair and was surrounded by parking lots. The raised platform is now the hub of 1.5 million square feet of development, with office, commercial and residential spaces built by Brightline’s owner.

Its rail cars, built by German industrial conglomerate Siemens and operated with diesel-electric locomotives on each end, come with features missing in many of Amtrak’s trains – some of which are 50 years old – including wide leather seats, an abundance of power outlets and strong WiFi.

Attendants bring coffee, alcoholic beverages and snacks for purchase to economy-fare travelers – items that are complementary to premium ticket holders. Passengers can schedule Uber connections to airports and other locations through the Brightline app, and the carrier offers free shuttle service at some stations.

Other differences compared to Amtrak include assigned seating – which Amtrak offers only on its Acela route and business-class fares on select trains – a security checkpoint before boarding and passenger use of conference rooms at stations.

Fares, which are comparable to Amtrak’s and competitive with airfare, vary depending on the time of travel and how early tickets are purchased. A ticket from Miami to West Palm Beach can cost between $15 and $52. Economy fares from Orlando to Miami start at $79 one way. Brightline will offer 16 daily round trips with hourly departures between Miami and Orlando.

The service carried more than 1.2 million people in 2022, with more than 1.1 million rides this year through the end of July. But the goal has always been linking two of the nation’s most tourist-friendly cities – Orlando and Las Vegas – with the nearby metropolis on each coast – Miami and Los Angeles – before taking high-speed rail nationwide.

“Florida is Version 1.0, and we think it’s a great 1.0,” said Wes Edens, the billionaire co-owner of the Milwaukee Bucks basketball team and co-founder of Fortress Investment Group, which owns Brightline. “Version 2.0, the high-speed rail from Vegas to L.A., we think is the real embodiment of what high-speed rail can and should look like. And that’s the system that people will look at and emulate when they look at building systems around the country.”

***

The 218-mile Las Vegas-to-suburban-Los Angeles route, dubbed Brightline West, has land, federal reviews and labor agreements in place, and company leaders say it could be built in four years. Its prospects are good, industry leaders and transportation officials say, amid renewed attention to rail in Washington and historic levels of federal funding for a national rail network that has lagged on the global stage.

Brightline West, expected to be funded primarily through private investment, like the Florida project, is also aiming for a multibillion-dollar federal grant.

Edens said history will repeat itself: The United States will have its first high-speed rail system just before it hosts its next Olympic Games – the 2028 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles. Brightline West’s target date coincides with start of the games.

Japan’s first bullet train from Tokyo to Osaka, now the world’s oldest high-speed rail line, opened 10 days before the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. China opened its first high-speed line, from Beijing to Tianjin, a week before the 2008 Beijing Olympics and has since built 26,000 miles of lines.

“It’s going to happen in the U.S. just like it did in China and Japan before it,” said Edens, who envisions a service modeled on the Paris-to-London Eurostar route and is already eyeing other corridors. “I think one [system] will quickly turn to two or three or four. I really believe that over the course of the next 20 to 30 years, you can see dozens of high-speed rails built in the United States.”

Among other projects at various stages, California is building a 500-mile system to connect Los Angeles and San Francisco that has been marred by delays and cost overruns. Its price tag, at $128 billion, is nearly quadruple the $33 billion project voters approved in 2008. A 119-mile section is under construction and projections call for a 171-mile segment connecting Merced, Fresno and Bakersfield to open between 2030 and 2033.

In Texas, a plan for a train connecting Dallas and Houston in less than 90 minutes has been slow to progress amid challenges in an environmental review, opposition from landowners and, more recently, a leadership exodus at the company developing the line. In the Pacific Northwest, a project is in the early phases of planning between Portland, Ore., Seattle and Vancouver, Canada.

While most of the $66 billion the infrastructure law allocated for rail will go toward upgrading existing track and replacing century-old tunnels and bridges along Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor, $12 billion is set aside for improving passenger services outside that region, including for high-speed rail.

Brightline West recently received a $25-million grant from the infrastructure law, while the California high-speed project has a $20-million grant for its Fresno station as it seeks $8 billion more. Other projects have requested federal funding.

Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, who rode Japan’s Shinkansen train this summer while at the Group of Seven summit, said funding through the law aims to boost an array of rail projects.

“I really think seeing is believing, and when we get even one of these up and running – which I do think can happen in this decade – then Americans will demand more,” he said.

High costs and a complicated federal approval process that can drag for years have stalled projects. Meanwhile, rail advocates and industry leaders say a decades-old “Buy America” mandate adds complexity. The policy requires federally funded transportation infrastructure to use U.S.-made materials, a challenge for a fledgling domestic industry.

Rep. Seth Moulton (D-Mass.), a self-described evangelist for high-speed rail and the former managing director of Texas Central, the company developing the Houston-to-Dallas line, has called for speeding up the regulatory process, particularly for rail projects that he said would benefit the environment.

“It’s a little bit crazy that we have an environmental policy act that hinders the development of projects that are fundamentally really good for the environment,” Moulton said at a recent conference in Washington. “There should be clear timelines.”

The United States has some of the most expensive transportation projects in the world, said Eric Goldwyn, an urban planning professor at New York University. His research found costs associated with governance issues, such as environmental reviews, and a U.S. tendency to build larger stations with longer construction timelines have made some projects cost-prohibitive.

While the infrastructure law made money available, experts say the biggest challenge is whether political and public support for rail can shift in a nation that moves by automobile. Traffic congestion and environmental concerns have not been significant incentives to reducing car dependency, said Robert Cervero, professor emeritus at UC-Berkeley’s City and Regional Planning Department, who cited increased car ownership during the pandemic as transit declined.

“We’re historically a far more car-oriented society, so it’s really hard for high-speed rail to get a foothold in the United States relative to some of the other advanced economies,” he said.

While demand for rail is high in densely populated corridors like the Northeast, Cervero said in city pairs such as Los Angeles-to-Las Vegas or Dallas-to-Houston, it might be difficult to sell intercity rail as a driving alternative because passengers at terminals probably still need a car to move around.

The 265-mile, electrified rail line from Las Vegas to Rancho Cucamonga, where it would connect to downtown Los Angeles via commuter train, is estimated to cost $12 billion – three times the price tag envisioned in the mid-2000s. Brightline submitted a 4,000-page application in April for a $3.75 billion federal grant from the infrastructure law.

A rendering of the Rancho Cucamonga station in Southern California planned by Brightline.

The grant is intended to cover nearly one-third of the project’s cost, officials said, while the company would use private capital and tax-free debt known as private activity bonds to finance the rest. An award would be one of the biggest infusions of federal funding on a privately developed transportation project in modern history, while it would give Brightline an important boost to break ground this year.

“We think that is a very efficient use of the public-sector dollars for the outcome that will ultimately be the stimulus that the industry has always been looking for,” Brightline chief executive Michael Reininger said.

Executive Michael Cegelis on the tracks near Brightline’s train maintenance facility in Orlando in June.

***

Las Vegas developer Tony Marnell II, the man behind construction of the Bellagio and Wynn Las Vegas resorts, pitched the idea of a bullet train in 2005 to connect the city’s casinos to Victorville, 85 miles from downtown Los Angeles in a rock-strewn expanse at the edge of the Mojave Desert.

Brightline’s 2018 acquisition of the project renewed hopes for the ailing line. The company has since secured land for four stations and right of way in the median of busy Interstate 15 to build high-speed tracks.

To connect to Los Angeles, Brightline proposed extending the line from Victorville to Rancho Cucamonga, which has a downtown L.A. commuter rail connection. The Federal Railroad Administration finalized its review for that 49-mile extension in July, finding no significant environmental impacts.

Project officials eventually plan to take the line to Los Angeles Union Station and connect with other rail systems. The line would fill a gap in Amtrak’s network, which hasn’t served the Las Vegas-to-L.A. corridor in 26 years.

For its part, Amtrak is also pushing a major expansion. It plans to increase speeds in the Northeast and expand to new cities nationwide. Among its proposed new routes is service in possible Brightline markets: Miami and Orlando, and restoring the train connection between Las Vegas and Los Angeles.

While Amtrak has proposed investments in short-haul routes – those generally less than 400 miles – the railroad would not be able to operate fast trains. Outside the Northeast, Amtrak trains use freight lines, with which speeds are typically below 80 mph.

Brightline’s Miami-to-Orlando service would be quicker than Amtrak’s trip time, which takes between five and seven hours via two long-distance routes.

Amtrak chief executive Stephen Gardner said the company welcomes the competition. He said as Brightline grows and other systems are built, he expects opportunities for Amtrak to connect with other networks.

“We’re supporters of intercity passenger rail, so I am excited to see other folks who see opportunities in what we do,” he said. “Trains have a role to play in the 21st century, so anybody who shares that vision, we see as our ally.”

A passenger approaches his train for departure inside the Brightline Miami station on June 6.

Support for Brightline is widespread in Nevada and California, where trains would travel in the median of I-15, one of the nation’s deadliest major highways. Federal and state officials say the proposed rail line would be a safer alternative and an environmentally friendly solution to the area’s chronic congestion.

Fifty million trips are made between Southern California and Las Vegas each year, mostly via private vehicles, according to project ridership studies. Brightline wants to capture 11 million of those trips annually.

Rep. Jimmy Gomez (D), whose district includes downtown Los Angeles, said the project is critical for environmental goals and alleviating the miles-long backups on I-15. Gomez, along with other members of the California and Nevada congressional delegations, recently signed a bipartisan letter to Buttigieg expressing “strong support” for Brightline’s $3.75 billion application, filed jointly with the Nevada Department of Transportation.

Buttigieg, whose office will decide whether Brightline receives federal funding, wouldn’t comment on the company’s competitive prospects but said the administration welcomes the private sector’s investment.

“Obviously, we love Amtrak. We also love any step that would bring more capital to the table to deliver good railroad service to passengers, and our job is to invest in the infrastructure that helps make it a reality,” he said. “We’re full-steam ahead, no pun intended, on passenger rail in America. And if private capital is part of what it takes to get that done, so much the better.”

Andy Kunz, president and chief executive of the U.S. High Speed Rail Association, said advocates want the infrastructure law to support projects that are ready to be built, like Brightline West.

“We can’t wait another 30 years to build a rail system,” Kunz said. Completing one project, he said, would give the nation a taste of the type of rail service only available internationally.

A rendering of the Las Vegas station planned by Brightline.

***

Back in South Florida, Liliana Rodriguez takes the train about weekly to her daughter’s house in Boca Raton, where she’s been helping care for her two grandchildren. The rail option avoids the 50-mile drive on congested I-95.

The fares add up, Rodriguez said, but the system’s reliability and efficiency has given her the ability to consistently move between the two cities.

“It’s magnificent,” she said. “I can spend time with my grandchildren and come back home if I need to. I imagine what it would be like when they open to Orlando. We can finally go without driving.”

The company said it expects most customers will be Florida residents traveling between the two cities, as well as tourists – particularly those from Latin America – who might be reluctant to rent a car. Brightline is also betting that air travelers from the West Palm Beach area will take the train to Orlando’s airport.

When train tickets to Orlando went on sale in mid-April, Joshua Wallack was one of the first to buy. He said he wants to be on the debut train from Orlando to Miami, a trip he frequently makes via Florida’s Turnpike that can easily go from a 3 1/2-hour drive to a five-hour nightmare.

Wallack, the chief operating officer at a bar and restaurant with a location in both cities, said Brightline will change Florida.

“Imagine the productivity difference. The whole time I’m writing emails, I’m making calls, I’m returning texts,” he said. “I don’t have to drive.”

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan