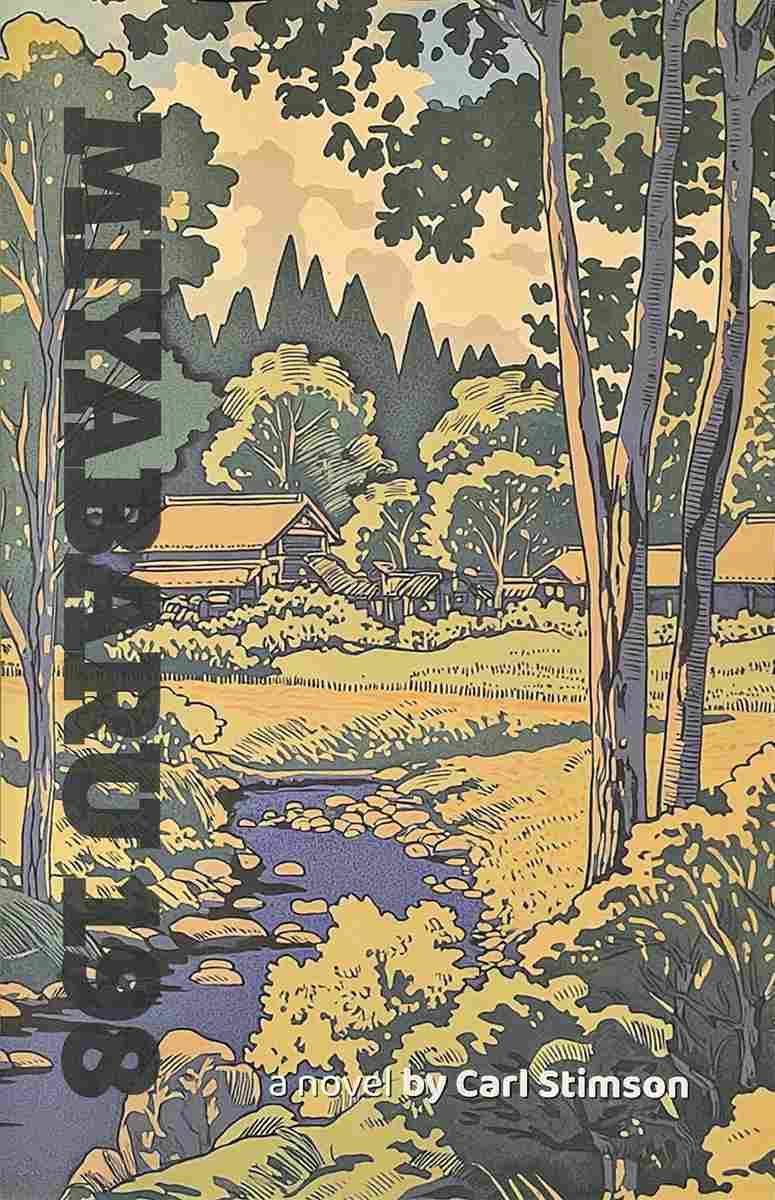

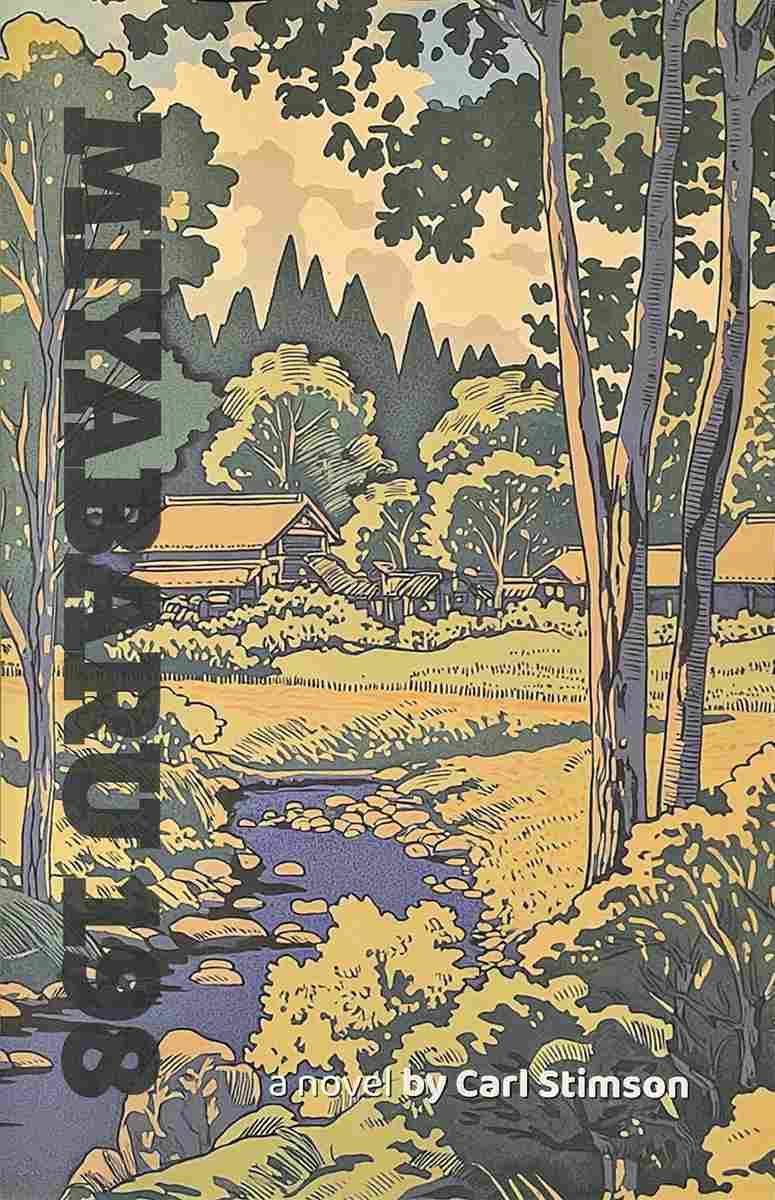

Bound to Please / In “Miyabaru 198,” a Hamlet with Centuries of History Faces an Unpeopled Future

‘Miyabaru 198’ By Carl Stimson

11:47 JST, January 2, 2025

What do you do when a town and all its centuries of traditions are about to vanish? There are many rural places in Japan that would like an answer. These are places that have been in decline for years, due to low birth rates nationally and the magnetic pull of the country’s metropolises. In many cases, people will keep leaving, and the towns will keep hollowing out. But at least we can remember these places before they’re gone.

In “Miyabaru 198,” a collection of short stories and one essay by author Carl Stimson, a small town in Kyushu gets just this sort of tribute. In the year 512, a scouting party travels out into the wilderness of the mountains, finding a spot “above a fine tributary valley to the west of the main river” where they can settle. And soon enough, they’ve planted their first rice crop and the town begins its long history.

But the town’s beginning is not the book’s beginning. Starting from the late 1950s, the stories in this collection telescope backward through time, through World War II, the Meiji period, the Edo period, the Sengoku period and back farther and farther still into the mists of pre-civilization. All this ambitious reimagining of decades and centuries past then ends in an essay, which adds context to the short stories and looks toward an uncertain future. Like its cousins throughout Japan, Miyabaru is now facing extinction as its population dwindles.

The styles of the storytelling are almost as varied as the period settings. Several stories are told in simple third-person narration, like the first story, which follows a farming family in the hamlet and a son who chafes at his parents’ penny-pinching. But there are also stories that function as broad narratives with no protagonist. The Edo period piece, for example, charts the long decline of the tea industry in Japan, which is first sent tumbling by an isolationist government and then drops off a cliff when there is more supply from elsewhere, particularly from British-held India. In the interplay of markets, nativism and global competition, the period can feel strangely familiar.

And of course there is the final essay, which completely breaks from the fictional voice, somewhat like the nonfiction chapters that are inserted into “War and Peace.” Here Stimson, who spent a decade in rural Kyushu, tackles with delicacy the question of how we should feel about the loss of Japan’s towns. Is it heartbreaking? Yes, since some traditions will be lost forever. Is there any good in this? There is. Nature, so long abused in Japan, will be given some space to breathe.

While ultimately we are left to make of this trend what we will, Stimson paints a bleak view of what awaits Japan’s hinterlands: “In many areas human habitation will cease … homes will be left to be torn down by the vines, crushed by falling trees, and swept away by rain and mud. Weeds and roots will crack paved roads, and the power company will come in to roll up its wire.”

So much around us is disappearing all the time: the world’s languages, the coral reefs, summers where you don’t have to mop yourself off the floor. At least Miyabaru got itself an elegy.

Miyabaru 198

- By Carl Stimson

- Independently published, 159pp, ¥2,176

Top Articles in Culture

-

BTS to Hold Comeback Concert in Seoul on March 21; Popular Boy Band Releases New Album to Signal Return

-

Director Naomi Kawase’s New Film Explores Heart Transplants in Japan, Production Involved Real Patients, Families

-

Tokyo Exhibition Offers Inside Look at Impressionism; 70 of 100 Works on ‘Interiors’ by Monet, Others on Loan from Paris

-

Traditional Japanese Silk Hakama Tradition Preserved by Sole Weaver in Sendai

-

Japanese Byobu Folding Screens Tailored to Meet Modern Lifestyles; Foreign Orders Also Piling up

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan