Gifu Museum’s Contemporary Art Exhibits Move the Soul; Two Artists’ Work Focuses on Theme of Time

Keiko Miyamori stands in front of her art installation using washi papers in Ikeda, Gifu Prefecture, on June 5.

16:44 JST, June 17, 2024

IKEDA, Gifu — The Kyokushou Bijutsukan museum has no admission fee nor charges for its predominantly contemporary art exhibitions. Located in a somewhat inconvenient spot at the foot of Mt. Ikeda in Ikeda, Gifu Prefecture, the museum is unique as it only accepts guests by reservation. On June 5, during my recent trip to Gifu Prefecture, I visited two artists’ exhibitions with the theme “Time.”

The Kyokushou Bijutsukan museum, formerly a private residence, at the foot of Mt. Ikeda in Ikeda, Gifu Prefecture

The small three-story museum was converted from a private residence and an attached warehouse. Chimei Nagasawa, a sculptor and former high school art teacher, invested his money in the hope of encouraging young artists and opened it in 2009. The first and third floors are exhibition rooms, while the second floor serves as an office and a place for people to interact. Two separate artists always have exhibitions on the first and third floors during the same period. When I went, the two artists were local painter Zuisho Suzuki and contemporary artist Keiko Miyamori, based in Yokohama and New York. Their works were exhibited until June 9.

“I draw in my croquis sketchbook what comes to me when I close my eyes at night before going to sleep.” Suzuki picked me up at the nearby JR Ogaki Station and began to talk as she drove. “I started in May 2003, and I’ve been drawing every night without fail. However, I did not do anything on March 12, 2011, the day after the Great East Japan Earthquake. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I think I must have been shocked by the images of the tsunami.”

-

Zuisho Suzuki stands amid her art, with copies of drawings from her croquis books displayed on the right, and paintings based on those drawings on the left. She draws what comes to her when she closes her eyes before going to sleep.

-

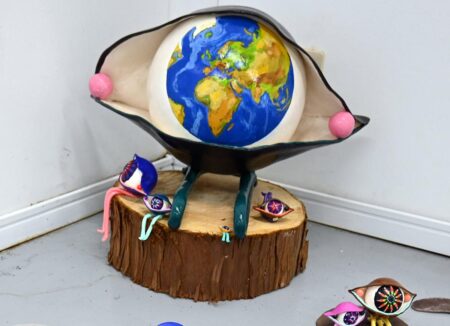

Eye-shaped figures called Messe-jin that are another of Suzuki’s works

-

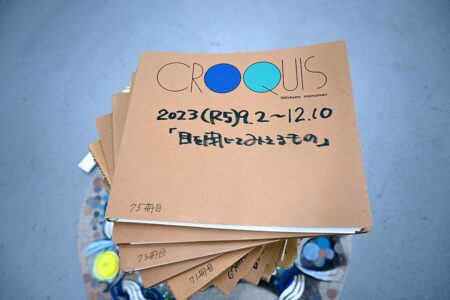

Suzuki’s 75 croquis sketchbooks used over the years are seen in a stack in the exhibition.

-

Zuisho Suzuki’s croquis books

I saw a stack of 75 of her croquis books when I entered the exhibition room on the first floor. She is currently on her 77th book and approaching the 8,000th day. Influenced by her daily state of mind and social circumstances, the drawings are of various shapes that include geometric patterns and swirls. The walls were full of her paintings based on them.

Small clay figures with an eyeball and legs were also displayed. Suzuki calls them Messe-jin. At first, she created them using the colors of the Ukrainian flag and flowers and such, wishing for an end to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. However, as the conflict has become prolonged, she is now creating various types of Messe-jin wishing for peace on the entire planet.

Expressing time with tree rubbings

Miyamori holds a large piece of jutaku tree rubbing collected for the exhibit.

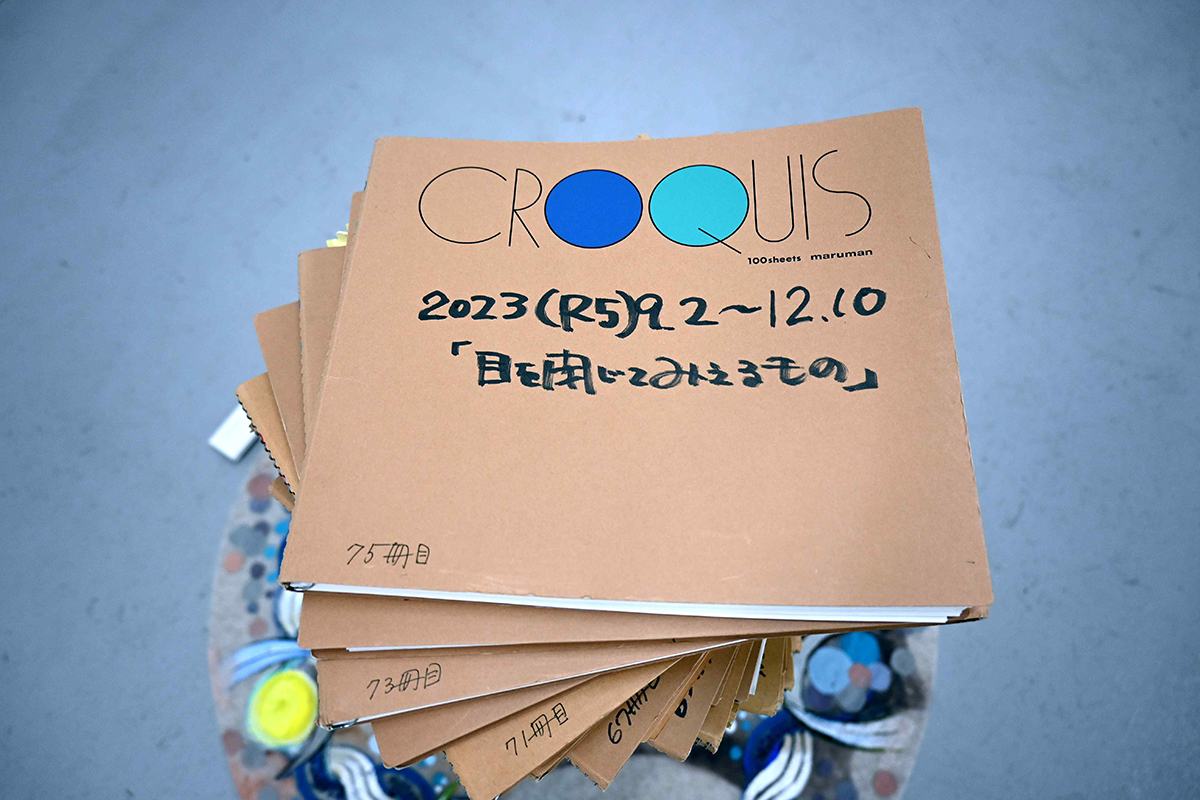

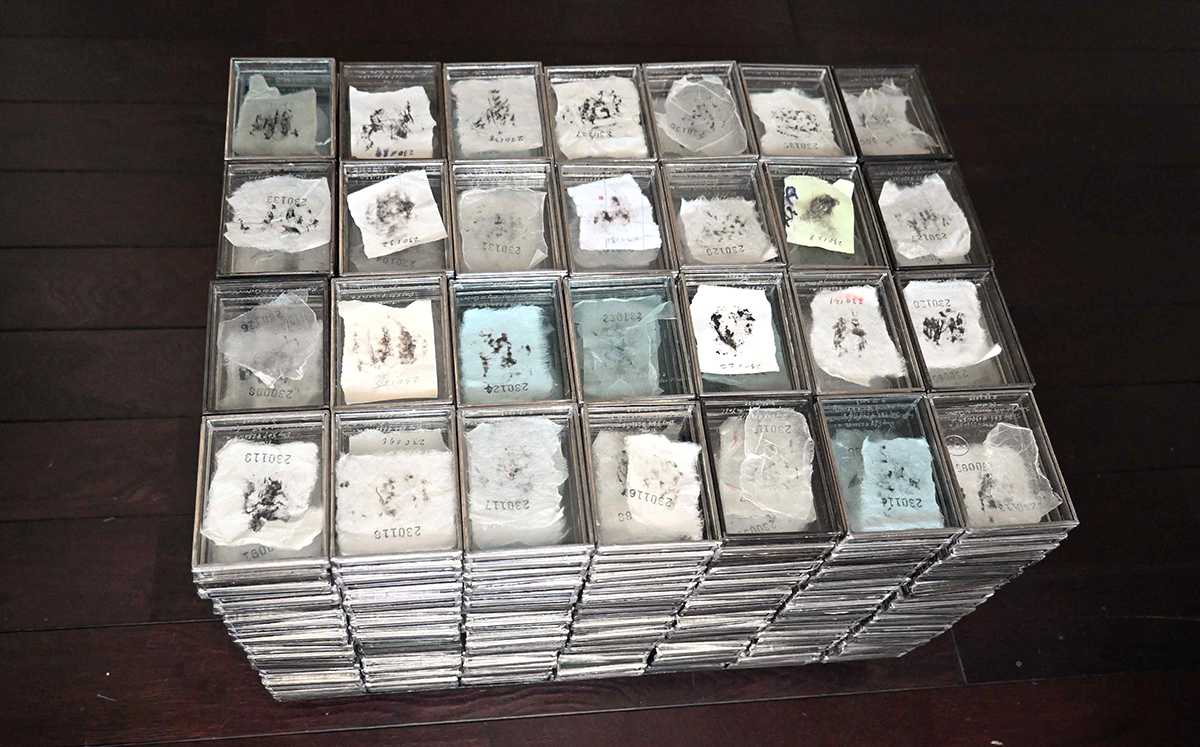

“I’ve been doing my TIME project every day since October 2021,” explains Miyamori, who returned to Japan to take care of her father and lives in Yokohama. “I place a small sheet of washi paper on the surface of a tree, then rub charcoal, which I made myself, over the paper to copy the bark’s patterns. I call it jutaku, and in art terminology, it is called frottage.”

Jutaku, literally translated to tree rubbing, does not damage the tree. Depending on where Miyamori is that day, such as the grounds of a shrine or a park, she will choose a tree for her jutaku. She makes two small jutaku pieces and places each in a clear, colorless glass case. When one sheet is owned by someone or sold to someone, she places the remaining one in a blue glass case. By arranging the jutaku cases collected so far, the clear and blue cases create a mosaic pattern, expressing the accumulation of time and the connection between people.

Miyamori presented me with a jutaku collected on my birthday, which means that I also participated in her TIME project. A collection of 588 days’ worth of jutaku were stacked in the exhibition room on the third floor.

Miyamori’s jutaku are seen in small glass cases, with blue cases indicating that one of the two pieces is owned by someone.

The exhibition also featured an installation of several large sheets of washi paper hanging from the ceiling to the floor, with dried rose petals and other materials on the floor. On the first day of the exhibition, dancer Juri Nishio, doused in water, tore the curtains of washi paper through slow and deliberate movements. Videographer Soma Ban recorded the performance, and it was projected on the torn washi paper throughout the exhibition. “I wanted to share that time with people, so they could witness the moment the beautifully thin washi papers were torn,” Miyamori said.

In this small museum, standing in the midst of a relatively remote landscape that could be anywhere in Japan, I was immersed in the world of two unique artists. Their art exhibitions touched my heart more strongly than if I had viewed them in a modern art museum in an urban area.

Top Articles in Culture

-

Director Naomi Kawase’s New Film Explores Heart Transplants in Japan, Production Involved Real Patients, Families

-

Traditional Japanese Silk Hakama Tradition Preserved by Sole Weaver in Sendai

-

Exhibition Featuring Yoshiharu Tsuge’s Manga World Underway in Chofu, Tokyo; Unique, Surreal Works Draw Steady Crowds

-

2 Unpublished Early Novellas by Japan’s Kenzaburo Oe Discovered, Show Budding Promise of Future Nobel Prize-Winning Author

-

Japanese Film, Anymart, Wins Critics’ Award at International Film Festival in Berlin, Director’s Debut Feature Film Shocks Audiences

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages Caused by Fraudulent Actions Without Waiting for Third-Party Committee Review