74-Year-Old Japanese Mountaineer Promotes Eco Practice to Protect Hometown Mountains: “Take Everything Home with You”

13:12 JST, March 26, 2025

NAGANO — Yoshitomi Okura, a 74-year-old mountaineer from Iida, Nagano Prefecture, advocates “eco mountaineering,” a way of climbing mountains without placing a burden on nature. He has put it into practice in the mountains of the Southern Japanese Alps, where magnificent nature still remains.

“The only thing you can leave behind in the mountains are your footprints,” Okura said, citing his motto.

A rental campsite set up by Yoshitomi Okura

He has set up rental tents to replace mountain huts and promotes the use of portable toilets.

He has also been active as a mountaineer since his 20s, and has scaled many 8,000-meter peaks in the Himalayas. He participated in the University of Alaska’s weather observation on Mt. McKinley, or Denali, the highest peak in North America, for about 30 years. Carrying equipment on his back, he has made numerous round trips to the mountain during the harsh winter months.

In 2019, when nearing his 70th birthday, Okura handed over his observation duties to his successor. He wondered if there was anything he could do in his hometown mountains. After returning to Japan, when he was searching for the purpose of the next phase of his life, what came to mind was the scenery of the Southern Japanese Alps that had impressed him in his youth.

This mountain range is home to such famous peaks of Mt. Hijiridake and Mt. Tekaridake, both among the Hyakumeizan, or the 100 most famous mountains in Japan. The area offers a magnificent natural environment with large Japanese spruce and cypress trees and grouse.

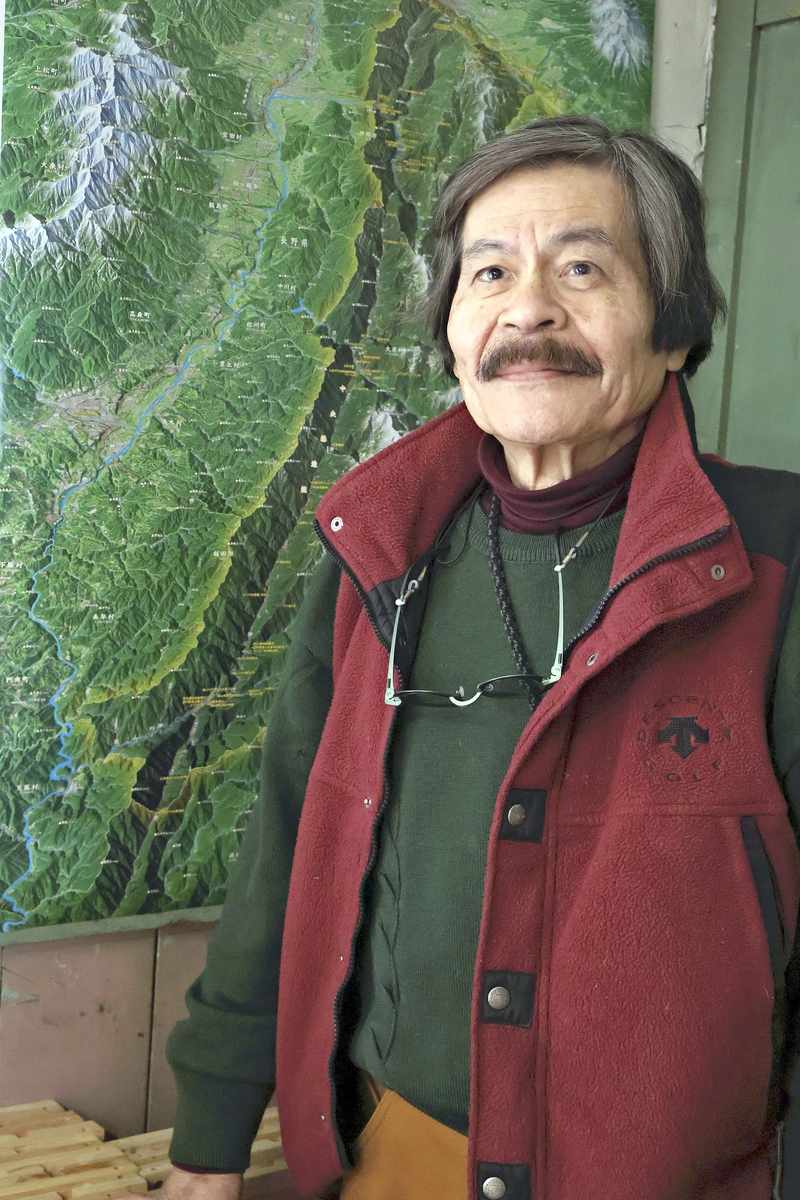

Yoshitomi Okura

On the other hand, the area is not for the general public, as there are no mountain lodges along some of the routes and, at the time, only about 800 people from the wider prefecture visited annually.

He also hoped to attract people through eco mountaineering, and revitalize the local community.

“One can do anything in a place where there is nothing,” he said.

The first step of action was setting up a rental campsite, because it made it easier to later restore the site to its natural state, compared to dismantling a mountain hut. Ten rental tents were set up for climbers at the site called “Mendaira” on the ridge on the west side of Mt. Irodake in 2020 and at “Nishisawado,” the entrance to the ridge leading to Mt. Hijiridake, in 2021.

Climbers receive keys in advance for the tents, which come equipped with mattresses and cooking utensils, allowing climbers to hike with relatively light luggage.

Portable toilets are another pillar of the eco mountaineering program. The basic rule in the mountains of the world, including Mt. McKinley, where he stayed for a long time, was that “people bring back home what they produce,” including excrement.

To protect the mountains’ natural state, Okura has received support from companies to cover the costs of handing out the portable toilets to climbers at mountaineering consultation centers at mountain entrances.

Five booths were set up at campgrounds and on mountain trails to use when defecating, and now he feels they have been widely accepted among hikers.

The number of climbers from the Nagano Prefecture side of the mountain reached about 6,000 in 2023, 7.5 times the number in 2019, when Okura started his efforts. He is taking on new challenges, including introducing a consultation center for safe mountaineering, online mountain climbing registration systems and drone searches for people lost in mountains.

“This place is part of my childhood memories. I want to be useful for helping protect the mountains here,” Okura said. He continues to pour his passion into his work.

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Tokyo University of the Arts Now Offering Free Guided Tour of New Storage Building, Completed in 2024

-

Exhibition Shows Keene’s Interactions with Showa-Era Writers in Tokyo, Features Newspaper Columns, Related Materials

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (1/30-2/5)

-

Prevent Accidents When Removing Snow from Roofs; Always Use Proper Gear and Follow Safety Precautions

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan