30 Years After Sarin Attack / Doctor at Tokyo Hospital Recalls Flood of Patients; Many Still Suffering Aftereffects

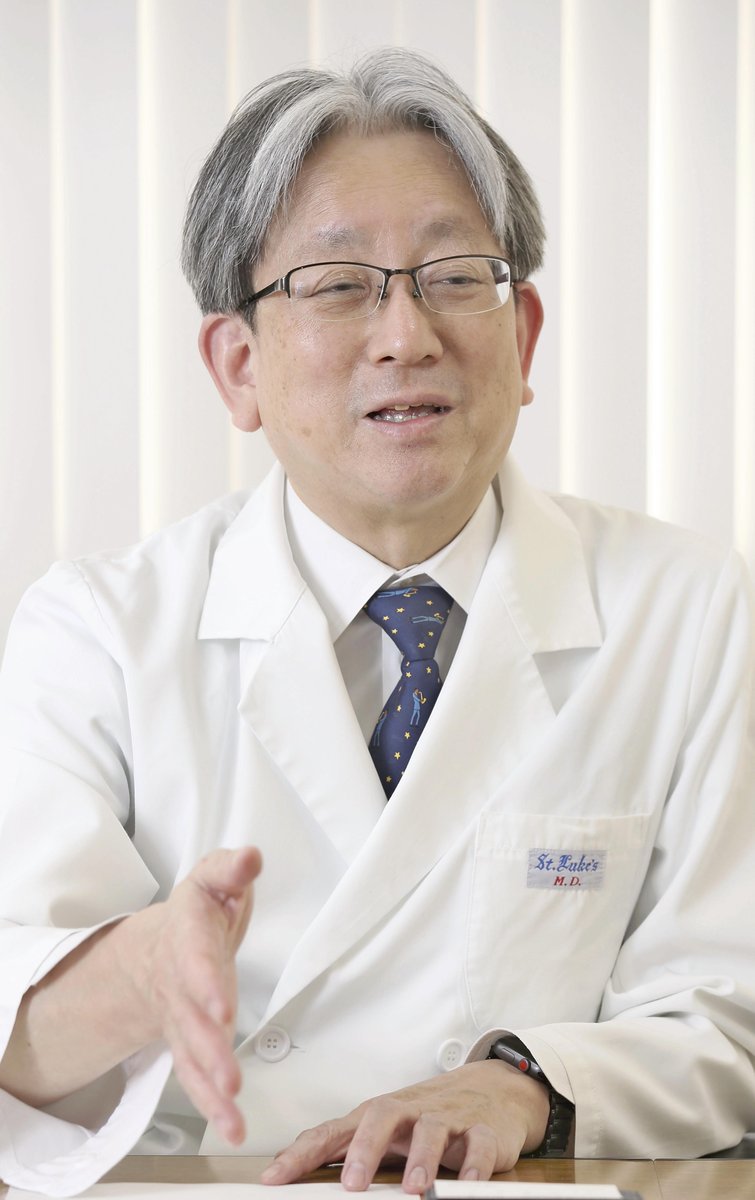

Shinichi Ishimatsu

By Mayumi Oshige / Yomiuri Shimbun Staff Writer

2:00 JST, March 4, 2025

Shinichi Ishimatsu, 65, is the director of St. Luke’s International Hospital in Chuo Ward, Tokyo. He was the deputy chief of the hospital’s emergency department on March 20, 1995, the day the Aum Supreme Truth cult carried out the deadly sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway system. Reflecting on treating patients in the confusion following the attack, he stressed the need for continued support for the victims in an interview with The Yomiuri Shimbun.

The following is excerpted from Ishimatsu’s comments during the interview.

The first ambulance arrived at the hospital at around 8:40 a.m. It was carrying a middle-aged man, and he was complaining of pain in his eyes and having difficulty breathing.

While we were trying to figure out what had happened to him, a young patient in cardiopulmonary arrest was brought in. After that, the patients just kept coming.

At around 10 a.m., we received information on sarin from several parties, including Shinshu University Hospital, which had treated patients after the sarin gas attack in Matsumoto, Nagano Prefecture, the previous year.

However, I couldn’t be sure that the same gas had been used in the attack on the subway system. It was feared that administering 2-PAM (2-pyridine aldoxime methiodide), a medicine effective in cases of sarin poisoning, might make the patients’ symptoms worse.

I had to consider whether I could take the responsibility of patients dying. I decided to administer 2-PAM, starting with seriously ill patients in the intensive care unit, as they could be immediately taken care of even if their condition got worse as a result of being given the treatment.

I was relieved when a young doctor told me soon after that the medicine had worked.

We received as many as 640 injured people on that day alone, and two women died at the hospital.

At the time, there were rumors that some of the perpetrators had fled to the hospital, and we were worried that sarin might be released inside.

What concerns me now is false information spread through social media. During times of disaster, we need to take measures to prevent false information from spreading, and the same is true during times of emergency.

A common aftereffect in many patients I have examined has been eye abnormalities. They have continued to struggle with blurred eyesight and difficulty focusing, among other symptoms. They also complain of feeling sluggish. The full extent of the injuries is still unknown.

I would have liked the national and local governments to have made efforts to ascertain the full extent of the damage, conducted follow-up surveys and provided mental and physical care to the victims from an early stage.

When I talk to medical professionals [about the attack], I always ask them whether they would be able to save as many people as possible if a similar attack took place tomorrow morning. I want to make use of what I learned in the past.

Implementing triage

Sarin is an extremely toxic organophosphorus nerve gas developed by Nazi Germany in the run-up to World War II. It can be inhaled or absorbed through contact with the skin and causes nerve and respiratory paralysis.

In the Tokyo subway sarin gas attack, senior members of the Aum Supreme Truth cult released the gas on subway trains running through the city center, injuring more than 6,000 people and causing medical institutions in Tokyo to be flooded with victims.

Medical institutions that accepted many patients in a short period of time were forced to carry out triage, in which the order in which patients are treated is based on the seriousness of their condition.

The idea of triage came to the fore in Japan following the Great Hanshin Earthquake in January 1995. However, it was still unfamiliar to many people during the sarin attacks just two months later. Some hospitals carried out triage for the first time in the aftermath of the subway attack.

Medical staff suffered secondary exposure as they dealt with patients before sarin was identified as the cause of the symptoms.

***

Shinichi Ishimatsu

Born in 1959, Ishimatsu graduated from the faculty of medicine at Kawasaki Medical School in 1985. He joined St. Luke’s International Hospital in 1993 as the deputy chief of the emergency department. In April 2021, he was appointed the hospital’s 11th director. He wrote “Sei to shi no genba kara” (From the frontline examining life and death), published by now-defunct Kairyusha.

Most Read

Popular articles in the past 24 hours

-

‘Dry Bonsai’ Gives New Life to Withered Trees, Allows Free Artist...

-

Japanese Students Use Traditional Pickle to Create Novel Wagashi ...

-

McDonald's Japan Raises Prices; Big Mac to Cost ¥500, Double Chee...

-

Nepal Bus Crash Kills 19 People, Injures 25 Including One Japanes...

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Rises as AI-Related Stocks Shine; Co...

-

Astellas Collaborates with Vir to Develop Its Experimental Prosta...

-

Early-Blooming Kawazu Cherry Blossoms Create Sea of Pink at Park ...

-

Joruri Bunraku Narrative Performed in Honor of Donald Keene by La...

Popular articles in the past week

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Sanae Takaichi Elected Prime Minister of Japan; Keeps All Cabinet...

-

Japan's Govt to Submit Road Map for Growth Strategy in March, PM ...

-

Bus Carrying 40 Passengers Catches Fire on Chuo Expressway; All E...

-

U.S. Firm to Build Training Hub in Fukushima N-plant for Debris R...

-

Japan, U.S. Name 3 Inaugural Investment Projects; Reached Agreeme...

-

Riku-Ryu Pair Wins Gold Medal: Their Strong Bond Leads to Major C...

Popular articles in the past month

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock ...

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo...

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reco...

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryuky...

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many Peop...

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages C...

Top Articles in Society

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

Woman with Measles Visited Hospital in Tokyo Multiple Times Before Being Diagnosed with Disease

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza