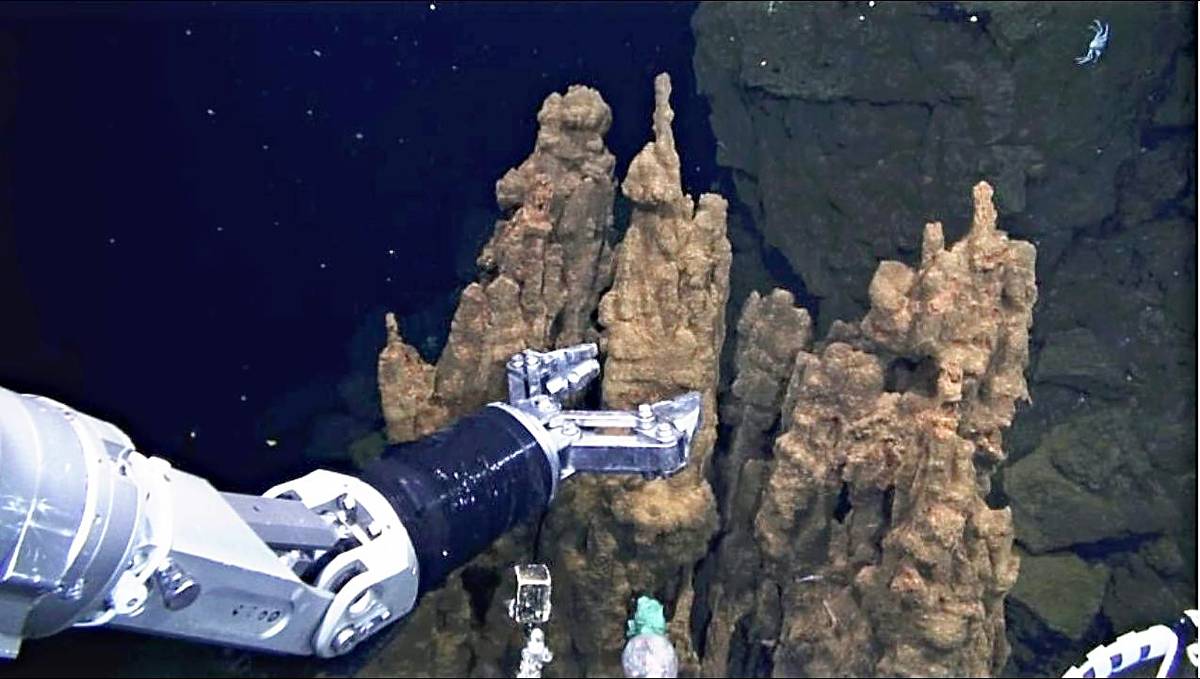

A robot arm breaks off a sample from an ocean “chimney.”

13:43 JST, February 26, 2025

A team of researchers has found that primitive microorganisms deep in the ocean survive by using the minerals around them. The team is led by Yohey Suzuki, an associate professor of earth and planetary science at the University of Tokyo.

The deep sea is one possible place where life on Earth began. The team’s finding may be key to explaining how primitive organisms survived during the first stage of evolution.

Earth’s organisms are divided into bacteria and archaea, monocellular organisms whose cells lack nuclei, and eukaryotes, which have complex cell structures.

Currently, it is widely accepted that archaea and bacteria branched off from their common ancestor sometime about 3.5 billion years ago. Eukaryotes then branched off from archaea and evolved into various organisms that finally became animals, including human beings. However, it was not understood how primitive organisms survived during the earliest stage of life.

The research team focused on natural chimney-like structures on a seabed deep in the ocean. There are vents in the seabed that blow out scorching water at hundreds of degrees Celsius, and minerals in this water solidify and form these chimneys.

Researchers believe that there were these undersea chimneys on Earth about 4 billion years ago, and they could have been where life first formed.

The team broke off part of a chimney on the seabed using a robot arm, at a spot about 140 kilometers off the U.S. territory of Guam. In gaps inside the sample, the team found primitive archaea belonging to a group called DPANN.

The DPANN group is comprised of primitive archaea that are similar to the common ancestor of all living things. These archaea have very small cells and genomes, which means they do not have the genes necessary for producing energy or synthesizing lipids, needed to create cell membranes.

Researchers had assumed that these archaea cohabitated with other microbes to compensate for biological functions they lack.

But the DPANN archaea that the team found survive with the help of the minerals around them, not thanks to other microbes.

The chimney’s inner wall is a mass of chalcopyrite, which is made up of iron, copper and sulfur. Substances from the vented water and the sea water had settled inside the gaps of the chimney. There was even silica, which is used in the bones and shells of organisms.

“It’s thought that the iron and other minerals in the chalcopyrite aid chemical reactions that provide energy, and that silica plays a role in preserving lipids,” Suzuki said.

Primitive lifeforms may have lived in this environment relying on these minerals until their descendants acquired the genes necessary for chemical reactions.

Next, the team of researchers will try to identify where the first organisms came into existence.

Top Articles in Science & Nature

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture