Bottles of Craft Sake brewed with Kyokai yeast cultures No. 1 through No. 6 distributed by the Brewing Society of Japan

20:41 JST, July 21, 2021

Rice, yeast, mold and water. To the list of elements that go into each glass of Japanese sake, perhaps one should also include passion and timing — two qualities Senjo, a brewery in Takato, Nagano Prefecture, knows better than most.

After 155 years of making sake it might seem like there would be little more to explore with the craft. But lately, Senjo has proved to be one of the rare brewers committed to revolutionizing its alchemical art, producing distinctive sakes that speak to the region’s rich subterranean water reserves and high-quality, locally harvested rice.

This month, Senjo launched a new initiative that invites customers to realize their brewmaster dreams and design their very own custom small-batch sake. Dubbed the “Craft Sake” project, the system gives customers unprecedented control over each step of the production process, from yeast, rice and water selection up through fermentation and the finishing touches.

The initiative is indicative of how Senjo has been seeking to shake up the struggling sake world, under the stewardship of its London-educated, sixth-generation president, Takashi Kurogochi.

I sat down with Kurogochi to learn more about his vision for the future of Senjo, and of course, sample some of the sake that his brewery does best.

Changing tastes

Senjo stands out among the rice paddies in the quiet Ina Valley. The landscape hasn’t changed all that much from the brewery’s early days — as glimpsed in the grainy, black and white photos that adorn the walls of a reception room at the company — but 44-year-old Kurogochi contends that the Japanese sake industry is in the midst of a paradigm shift.

“Breweries used to churn out cheap sake by the barrelful. But the days of mass consumption are long over. Now, the time has come to seek out and truly savor thoughtful sake, made with care for the discerning palate,” Kurogochi explained.

“As such, I reasoned that the new generation of clientele would enjoy going beyond simply purchasing our products and instead have an experience. Trying to calibrate a brew yourself really reveals how each choice affects the taste, hopefully for better rather than worse, with many surprises and insights along the way.”

Senjo’s managers and workers in the early days of the company.

Rice paddies surround the brewery.

Old sake bottles. The empty bottles were brought in to be refilled with sake.

Compared to craft beer, which has steadily hopped to the mainstream in Japan, craft sake is still a relatively untapped niche. The haute couture of the sake world, such small-batch brews have typically been the purview of boutique breweries, bottled under their own “jizake” labels. Even so, apart from the occasional high-flying collaboration (the recent Foo Fighters tie-up comes to mind), it is rather unheard of for brewers to hand over the controls to the common curious quaffer.

Senjo’s craft batches will be brewed over the summer, before the arrival of winter when the brewery becomes busy with the main business of making its own sake, including its flagship label, Kuromatsu Senjo. Industrial refrigeration systems will be used in the summer to recreate the same conditions of the wintry brews, which are key to cooling the steamed rice and controlling the fermentation process.

The first step is yeast selection. Many different varieties of yeast can be used to brew sake, each with its own unique characteristics, such as fermenting power and aroma. Yeast cultures can even be collected from cherry blossoms and lavender.

And to make sake, you of course need rice. For the time being, the brewery strongly recommends using locally grown rice, but said that in the future it plans accommodate a broad spectrum of rice upon request.

For water, look no further than the pristine underground reserves that are on constant tap, flowing directly underneath the brewery, down from the Southern Alps. But the brewery is open to experimentation. “If you brought us 100 or 200 liters of water from the North Pole, we could certainly make you North Pole sake,” Kurogochi chuckled, only half-joking.

Locally harvested and milled sake rice (Courtesy of Senjo)

The harvest season marks the start of the sake brew. (Courtesy of Senjo)

A shrine dedicated to the god of water is located on the premises. Underground water from the Southern Japanese Alps flows abundantly 60 meters beneath the brewery’s floors.

Trees on the brewery premises. Cherry blossoms flower in the spring.

With the broad brushstrokes out of the way, honorary brewmasters must next delve into the nuanced detail that will flesh out the flavor profile of their brews. After deciding on the type of koji, the magical mold that’s key to readying the rice for fermentation, clients can stipulate the temperature and duration of the koji-making process and fermentation. Forgo pasteurization and dilution to make nama-genshu, or opt for the usunigori option if you prefer a slightly cloudy sake. It will even be possible to store your batch in subterranean cellars to mature — if you can muster up the patience to wait.

The fruits of these labors will be delivered to your doorstep as fresh sake bottled in the standard 720 ml bottle size. The brewery plans to offer two pricing brackets — a 60 kg course and a 100 kg course — based on how much rice is used. Although final sake yield is proportional to the grain polishing ratio, 60 kg of rice will produce in the ballpark of 100 bottles, while 100 kg of rice is enough for about 166 bottles of sake. Pricing for 166 bottles starts at ¥330,000, but depends on the rice varietal, milling ratio, and other factors.

“If you happened to be in Nagano for a week or two, you’re also welcome to come and physically brew your sake together with us. We are glad to have foreign customers, too.”

To inaugurate the project, Senjo has been busy brewing six new craft sakes of its own, each made using one of the precious first six yeast strains collected from renowned sake breweries since the Meiji era (1868-1912) by the Tokyo-based Brewing Society of Japan. All six of the new craft sakes have been brewed under the exact same conditions, so that the different tastes and aromas of the yeasts can be showcased to their fullest. The brewery has begun offering the limited-edition brews to backers on a crowdfunding site. A full six-bottle set can be reserved for ¥15,000 (including tax and shipping within Japan), with delivery in October or November.

Quest for distinction

The history of Senjo is a mirror for the ebb and flow of the modern sake industry.

“After the war, there had been an unquenchable thirst for inexpensive sake. Breweries could hardly keep up with demand. We built this factory in 1984 with state-of-the-art equipment that would make mass production possible,” Kurogochi said.

“At the time, we received some flak from purists who opposed mechanization, arguing that sake is an art form, created by craftsmen with many years of experience. But we chose the path toward modernization, building this facility to produce sake in a hygienic, scientific way.”

The machine on the left cools the steamed rice. (Courtesy of Senjo)

Two large rice millers owned by the brewery. Each rice mill can mill 1200 kg of brown rice. They are in full operation during the busy winter season. Cannot be used for Craft Sake or other small-batch brews.

Large tanks for storing sake are lined up.

View of the huge tanks from below.

Large tanks used for high-volume brewing (Courtesy of Senjo)

This Ginjo Koshiki (steamer) can steam up to 300 kg of white rice. (Courtesy of Senjo)

Bottling production line

But by the time the new factory opened, the tidal wave of sake fervor had already long since crested. Sake shipments continued to dry up nationwide into the 1990s. Kurogochi said that when he joined the company in 2001, the despondence was palpable: “Sales were declining at an alarming pace every year, and it seemed there was nothing we could do about it.”

Ever since embarking on his career in an ailing industry, Kurogochi’s mission has been one of triage, and seeking ways to return sake to its former glory. Along the way, he came to believe that the only viable route for survival would be to increase the lineup of top-shelf sake, such as junmai ginjo and junmai, that were delicate enough to let Senjo’s unique identity as a brewery shine through.

To counter the generational shift as young people increasingly turn toward other beverages, Kurogochi has conversely proposed leaning in on the timeless characteristics that make sake quintessentially sake. He illustrates the principle by drawing parallels to the lasting appeal of automobiles, another industry that has been navigating a reversal of fortunes since its own full-throttle postwar years.

“As technology advances, self-driving cars might someday mean that we won’t necessarily have to sit behind the wheel to get around. But I think people will still take pleasure in participating in car races, because driving is, after all, fun. It’s like how horses are no longer needed as a mode of transportation, but equestrianism survives as an aristocratic pursuit. Something similar applies to sake. Although sake is no longer being consumed by the masses as before, I think it still caters to an eternal demand for enjoying the unique and satisfying our appetites for knowledge.”

Ironically, Senjo’s industrial-scale facilities posed a prohibitive bottleneck when it came to trying out Kurogochi’s less-is-more approach. Oriented toward mass production, the brewery was routinely converting 6,000 kg of rice into 15,000-liter batches of sake. This was far too many zeros to risk on an experimental batch — failure would mean literally pouring money down the drain.

The frustration at being unable to test his hypothesis weighed heavily on Kurogochi’s shoulders, along with the pressure of needing a breakthrough, fast.

This big breakthrough — or perhaps a saving grace — came in the form of a 100% koji amazake released by Senjo in 2005. Although made from fermented rice, amazake contains less than 1% alcohol, so is more of a sweet cousin to conventional sake, rather than a sake itself. At first, the product hardly made a peep. But around 2015, seven years after Kurogochi took the reins as president, sales skyrocketed as amazake became the latest overnight health trend.

Financially buoyed by the sleeper hit, the brewery was able to purchase two small new fermentation tanks, one 700 kg and the 1,500 kg. At last, Senjo was ready to dip their toes back into small batches of junmais and daiginjos, while still continuing production of their regular large-batch labels.

“The entire experience has given me an uncommonly strong passion for small-batch sake that I think few could rival,” Kurogochi said.

In 2017, the company resuscitated its traditional koji-making room — the heart of any brewery — after a 33-year hiatus. Although the brewery’s machines perform their job with aplomb, whipping up large volumes of koji without fail, there is something about making koji by hand the old-fashioned way, basking in the organic warmth of the wood-paneled room, that dramatically improved the quality of their small-batch sakes.

Work in the koji room. After sprinkling koji mold on the steamed rice, the rice is mixed evenly. (Courtesy of Senjo)

Medium-sized brewing and sake storage tanks. In winter, the tanks are used to brew about 1500 kg of rice. In the summer, they are used to refrigerate and store the finished sake. (Courtesy of Senjo)

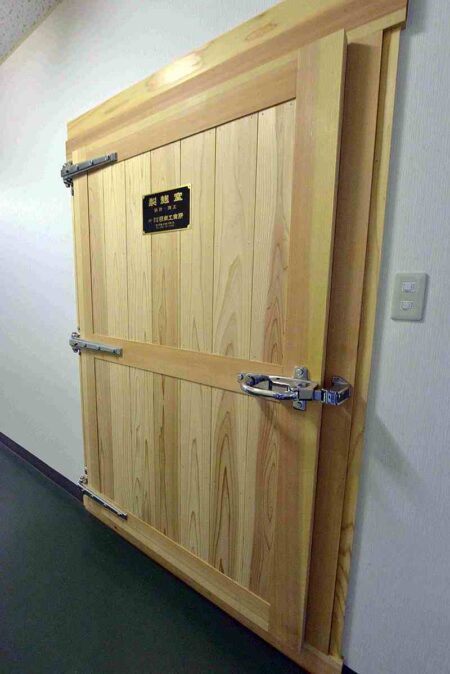

A wooden koji-making room revived in 2017 after 33 years.

The wooden door of the koji-making room also has its charm.

A stainless steel tank and refrigerator used mainly for brewing doburoku. The portable tank can be used even in summer and holds about 200 kg of doburoku. (Courtesy of Senjo)

Harnessing this newfound momentum, the brewery next created its masterful Kuromatsu Senjo Junmai Ginjo Kinmon Nishiki, which earned an admiring seal of approval from Richard Geoffroy, long-time chef de cave at Dom Perignon.

After rounding out its fleet with the acquisition of an array of even smaller, micro tanks, Senjo is poised to realize Kurogochi’s vision through the Craft Sake project this year.

Gin with a Japanese twist

“We plan to perfect a craft gin using Takato’s acclaimed cherry blossoms.”

Kurogochi is a gentle man with a quiet demeanor, but a fire burns in his eyes when he gets on the subject of the ambitious plans he has lined up for the brewery — plans that include diversifying their portfolio.

“Heirs of breweries like me tend to have a fixation on selling sake. They only think about things within the framework of sake. If something doesn’t fit squarely within that narrow framework, they see it as being somehow inferior. I confess that I used to be like them, too. Of course, it is important to have a firm footing in sake. But over time, I’ve come to think there are still other opportunities for people who want to step a little outside the box.”

Rice shochu. On the right is rice shochu stored in a sherry barrel. The brewery uses the rice shochu as a base for their craft gin.

A still used for making gin

Following the success of amazake, the brewery scored another hit with doburoku, an unrefined sake. The back to back successes convinced Kurogochi to take the plunge in earnest. Senjo began producing rice shochu that could in turn be used as a base to make craft gin, the botanical spirit that has been enjoying a renaissance both in Japan and abroad. This led the brewery to obtain a license to manufacture spirits, which serendipitously (and lucratively) branched into high-alcohol disinfectant amid the spread the coronavirus last year.

Cherry blossoms in bloom at the Takato Castle Site Park (Courtesy of Senjo)

Cherry blossoms inTakato

View from Takato Castle Site Park (Courtesy of Senjo)

Of course, gin boasts a long pedigree of its own in Europe. It is a complex spirit that does not necessarily translate easily. But Kurogochi has set out to identify local ingredients that resonate with the context in Nagano:

“My goal is to create a gin that expresses the cherry blossoms of Takano and the Southern Japanese Alps. [The difficulty is that] our brewery sits 2,300 meters below the mountain peaks, and the flora varies at each step along the way.”

Although that leaves a lot of ground to cover, Kurogochi’s team continues to search for their symbolic blend, through a painstaking process of trial and error.

Ambassadors for rice fermentation

“Sake, amazake, doburoku and shochu all have one thing in common: They are all made by fermenting rice. We’re putting forth a philosophy that integrates all of these drinks in the interest of furthering what I like to call the rice fermentation culture,” said Kurogochi.

Kurogochi’s fermentation proclamation grew out of a need to first persuade his own front line employees, who initially balked at the thought of brewing amazake. “We’re here to make sake, not amazake,” they grumbled.

In response, Kurogochi came up with the phrase “Rice Fermentation Culture,” which he integrated into the brewery’s brand identity, and featured on their website.

Koji is cooled and dried in the sake storage room. In the past, when refrigeration facilities were not available, koji was dried in a well-ventilated place like this. Nowadays, koji is partially dried with a fan and then stored in a cold storage room. (Courtesy of Senjo)

After steaming rice for about one hour, it is dug up with a special shovel and carried away. (Courtesy of Senjo)

If you want to steam two kinds of white rice at once, insert a divider cloth as demonstrated here. (Courtesy of Senjo)

Steamed rice is spread out on a slatted drainboard to cool. The newly steamed rice is too hot to be touched directly. (Courtesy of Senjo)

The spread out steamed rice is further mashed and mixed over while it is cooled to the target temperature. (Courtesy of Senjo)

Hot water used for sterilization is boiled in a stainless steel tank. (Courtesy of Senjo)

As sales of products other than sake increased, the employees began to more fully appreciate the philosophy. Most importantly, the success dispelled any lingering hesitations Kurogochi once harbored over the unorthodox approach: “Fermented foods are great for your health. Amazake is a super-healthy energy drink, made of water and koji alone. But it’s still largely unknown worldwide. I only see a bright future ahead for [introducing the world to] Japanese food and drink made from fermented rice.”

Kurogochi is confident that rice fermentation is primed to become a larger movement, one that could next help prop up the flagging Japanese rice industry—high proof of what Kurogochi has come to see as his brewery’s mission to enrich the local community and preserve the scenic vistas of Takato.

Senjo

https://www.senjyo.co.jp/

Known for the flagship label “Kuromatsu Senjo,” Senjo was founded in 1866 at the foot of the Southern Alps in Takato, Nagano Prefecture. Takato flourished as a castle town during the Edo period, nurturing a deep-rooted appreciation of culture and aesthetics epitomized by its famed cherry blossoms, which continue to draw a large number of tourists every spring.

The second-generation president of the brewery brought light to the town, when he founded an electric power company along with members of the prefectural assembly. In 1984, Senjo modernized with a new brewery and relocated from the town center to its present location in the outskirts. The factory is located at 2432 Takato-machi Kamiyamada, Ina City, Nagano Prefecture.

Takashi Kurogochi

Takashi Kurogochi was born in 1976. After graduating from the Department of History, Faculty of Literature at Keio University, he continued his studies in the history of international relations at the London School of Economics. Kurogochi joined Senjo in 2001, where he has served as the sixth-generation president since 2009.

- ■【Senjo】CrowdfundingCrowdfunding page for the Craft Sake project

- https://camp-fire.jp/projects/view/451220

- ■Inquires can be directed to

- info@senjyo.co.jp

Publish:Japanese version on Yomiuri Shimbun Online

"JN Specialities" POPULAR ARTICLE

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (12/12-12/18)

-

English-language Kabuki, Kyogen Entertain Audiences in Tokyo; Portland State University Professor Emeritus, Graduates Perform

-

Noodle Dining Shunsai / Rich Oyster Ramen to Savor at Odasaga; Experienced 68-year-old Owner Creates Numerous Ramen Varieties

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (12/5-12/11)

-

People Keep Loved Ones’ Ashes Close in Special Jewelry, Small Urns as Unique Way to Memorialize Them

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Keidanren Chairman Yoshinobu Tsutsui Visits Kashiwazaki-Kariwa Nuclear Power Plant; Inspects New Emergency Safety System

-

Imports of Rare Earths from China Facing Delays, May Be Caused by Deterioration of Japan-China Relations

-

University of Tokyo Professor Discusses Japanese Economic Security in Interview Ahead of Forum

-

Japan Pulls out of Vietnam Nuclear Project, Complicating Hanoi’s Power Plans

-

Govt Aims to Expand NISA Program Lineup, Abolish Age Restriction