8:00 JST, January 21, 2023

Japan’s government debt has been exceptionally high among major industrialized countries for over two decades. The risks posed by this massive debt must be properly analyzed and managed.

I recall that in June 2010, Japan was branded with a failing grade among developed countries at the G20 Summit in Toronto.

Many countries had decided to mobilize massive fiscal outlays to prop up their economies, which had suffered their worst postwar declines due to the financial crisis in the fall of 2008.

However, this enormous budget mobilization had led to the deterioration of each country’s public finances, posing a risk to international economic stability. As a result, fiscal consolidation emerged as a central theme.

In the Toronto summit’s Leaders’ Declaration, advanced economies pledged to at least halve their deficits by 2013 and stabilize or reduce their ratios of government debt to GDP by 2016. But the leaders treated Japan as an exception to this commitment.

I covered the summit as a correspondent for The Yomiuri Shimbun’s Washington bureau. At the time, the Japanese government tried hard to obtain the exception, believing that Japan’s fiscal situation would make it impossible to keep an international commitment of that kind.

When an economy takes a significant hit, it is proper to use fiscal stimulus to prop up the economy.

But even in the aftermath of the crisis, Japan continues to fail to show a stable path for debt management, which is a serious Japanese problem.

When making international comparisons of fiscal sustainability, it is helpful to look at a country’s outstanding debt relative to the size of its economy — as measured by gross domestic product — which is ultimately the source of its tax revenue.

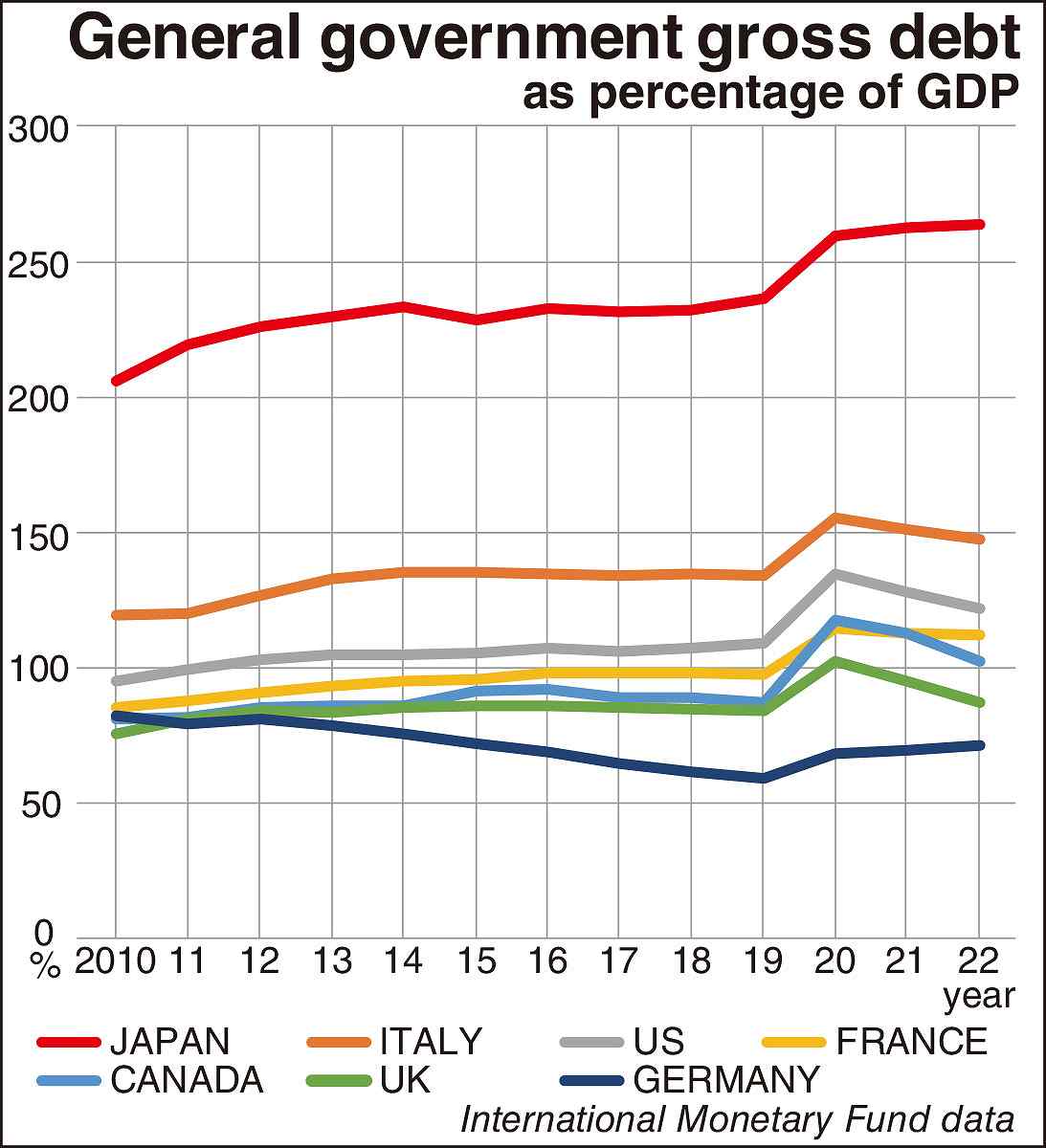

The chart accompanying this story shows the trends in general government gross debt as a percentage of GDP from 2010 to 2022 for the Group of Seven industrialized nations, based on data from the International Monetary Fund.

It is clear that Japan has made less progress in fiscal consolidation than the other G7 countries since 2010. Moreover, the gap has widened further due to stimulus measures implemented in response to the spread of the novel coronavirus.

The ratio of Japan’s general government gross debt to its GDP had already exceeded 200% in 2010. It is projected to be over 260% for 2022.

While Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio has worsened by more than 50 percentage points since 2010, the U.S. ratio rose just under 30 percentage points in the same period. Germany’s ratio declined by about 10 percentage points. No G7 country except Japan worsened by more than 30 percentage points.

Japan’s debt has ballooned with each crisis and has been slow to improve as the economy has returned to a more normal state.

Last month, the government approved a record draft budget of ¥114.3 trillion for fiscal 2023, setting a new record for the 11th consecutive year.

The number of new government bonds issued will be in the ¥35 trillion range, meaning one-third of the nation’s expenditures will be financed by debts.

There is no clear theory on the upper limit of the ratio of government debt to GDP.

Historically, however, the expansion of government debt often leads to hyperinflation.

Governments issue unlimited government bonds, and central banks print money to underwrite them. As a result, the currency loses credibility, and the value of the currency plummets.

The hyperinflation in Germany after World War I is well known.

Japan has had a similar severe experience.

At the end of fiscal 1944, during World War II, when the cost of the war was high, Japan’s ratio of government debt to GDP was similar to the historically high level seen today. Therefore, immediately after the war’s end, reducing government debt became a significant challenge to ensure fiscal sustainability. As a result, the government reduced its debt by implementing a “deposit blockade” and imposing property taxes at rates of up to 90%, siphoning off assets from the public, rich and poor alike, in the form of taxation.

The lesson to be learned from the history of Germany and Japan is that the people had to bear a tremendous burden to reduce the ballooning debt.

Of course, since today’s economic and fiscal structures are different, the situation at the time cannot be simplistically compared to the present one.

However, we should be aware that it is difficult to know when damage will occur, and how severe it will be, if government debt continues to balloon.

Hiroshi Nakaso, who served as deputy governor of the Bank of Japan from 2013 to 2018 and was responsible for the massive monetary easing measures, sounds the alarm in his recent book, “The Last Line of Defense.”

“The loss of confidence in public finances likely does not occur in stages. A decline in confidence in Japanese government bonds could begin abruptly at some point after the market changes its view.”

If government bonds collapse, Japanese financial institutions and pension funds will suffer huge losses, and many banks will go bankrupt. Not only would pensioners be struck, but the value of the public’s savings would also plummet, with a catastrophic impact on the economic life of the nation.

It is necessary to continuously work on fiscal soundness and stable debt management from a risk management perspective to prevent shocks.

Japanese people tend not to be good at risk management, which involves assessing the quantity and quality of risks and taking appropriate countermeasures.

We are risk-averse because safety is considered a prerequisite in various matters. We so intensely dislike taking risks that we have a strong zero-risk orientation.

Paradoxically, this zero-risk orientation itself tends to bring about a reluctance to look squarely at risks that are difficult to grasp.

The difficulty in ascertaining when and how a debt disaster will strike is similar to that of a significant earthquake. Japan has been preparing for earthquakes by refreshing its memory of the damage caused by repeated earthquakes of the past.

However, the fiscal collapse of nearly 80 years ago is a distant memory.

Furthermore, the Bank of Japan’s massive monetary easing and purchases of government bonds have suppressed the rise in long-term interest rates, making it difficult for us to be aware of the risk creeping up.

Thus, politicians and the government have a heavy responsibility to analyze risks more deeply, to strengthen debt management, and to give an accounting to the public.

“There’s no such thing as a free lunch” is an economics adage. If you borrow money, you must pay it back. Inflated government debt inevitably brings a burden to the people. So we must heed the adage’s warning.

Political Pulse appears every Saturday.

Akihiro Okada

Okada is an editorial writer for The Yomiuri Shimbun.

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

40 Million Foreign Visitors to Japan: Urgent Measures Should Be Implemented to Tackle Overtourism

-

AI, Initially a Tool, is Evolving into a Partner – But is it a Good One?

-

University of Tokyo Professor Arrested: Serious Lack of Ethical Sense, Failure of Institutional Governance

-

Greenland: U.S. Territorial Ambitions Are Anachronistic

-

Policy Measures on Foreign Nationals: How Should Stricter Regulations and Coexistence Be Balanced?

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan, Qatar Ministers Agree on Need for Stable Energy Supplies; Motegi, Qatari Prime Minister Al-Thani Affirm Commitment to Cooperation

-

Australian Woman Dies After Mishap on Ski Lift in Nagano Prefecture