Bound to Please / Scholar Reveals Real-Life Characters Behind the Fiction of ‘Shogun’

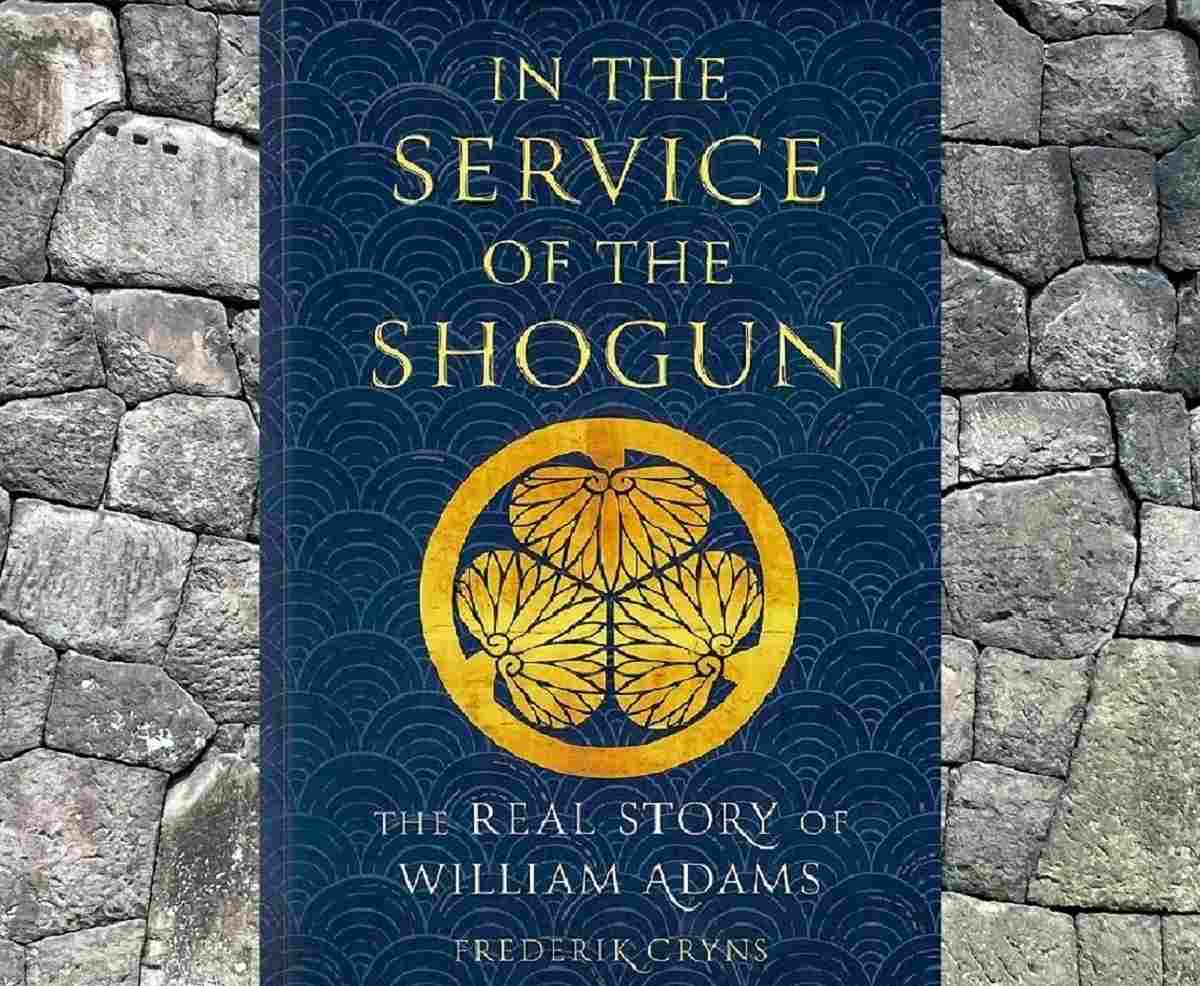

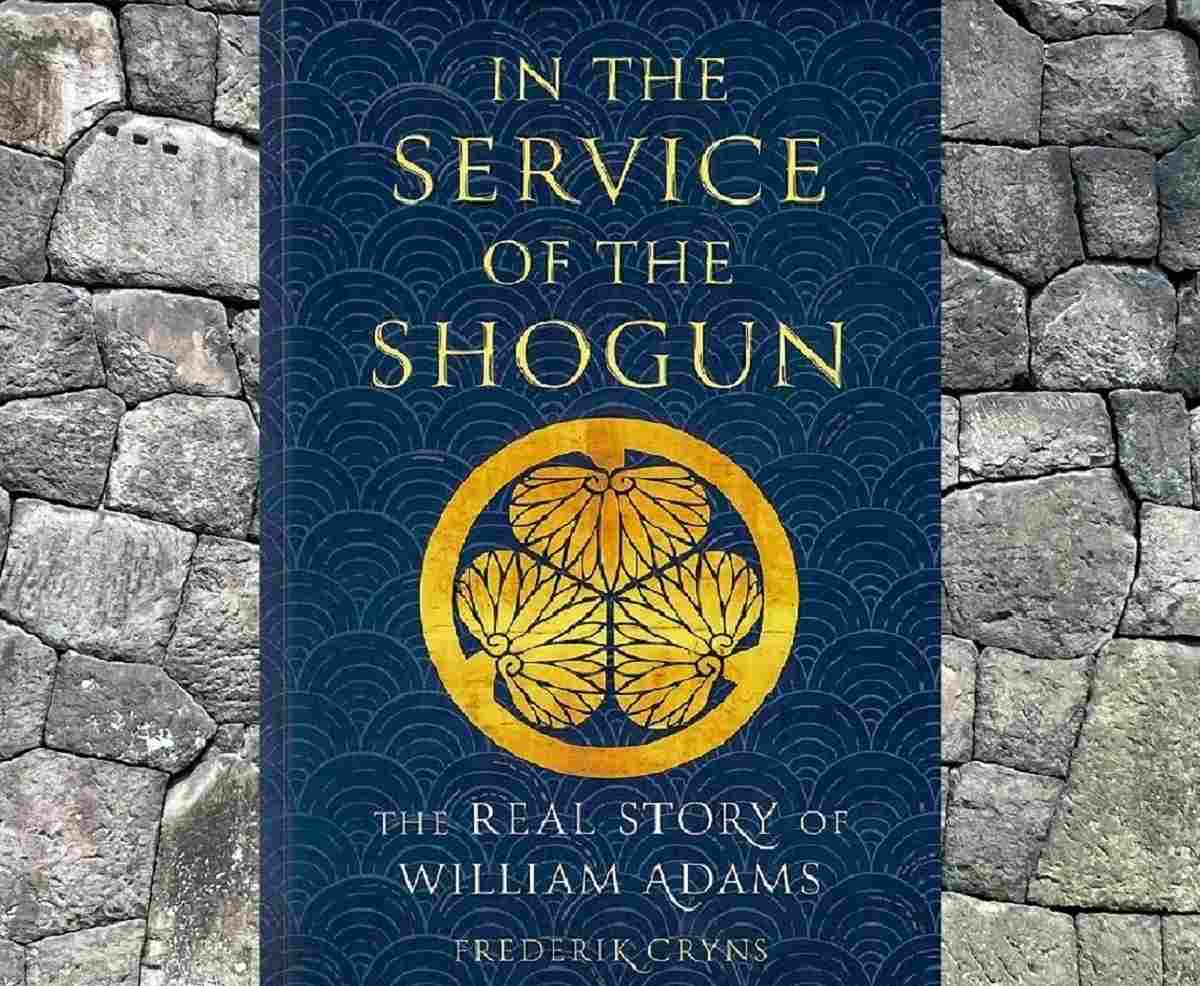

“In the Service of the Shogun” by Frederick Cryns

13:56 JST, July 18, 2024

“We’ve endured pestilence, known starvation, chewed the calfskin that covers the ropes. We should be corpses by now.”

In the first episode of the TV series “Shogun,” based on the James Clavell novel, English seaman John Blackthorne speaks these words to his Dutch crewmates in the year 1600, reminding them of the hardships they shared on their journey to Japan. After this humble start, Blackthorne meets a Japanese warlord named Toranaga and gets caught up in a violent struggle for control of the nation.

The TV show’s plot is fiction, but it borrows elements from history. Blackthorne is based on a real person named Will Adams, and Toranaga is modeled on Tokugawa Ieyasu, who moved Japan’s capital to Edo and became the founding shogun of a dynasty that would last until 1867.

Frederik Cryns, a professor at the International Research Center for Japanese Studies in Kyoto, is listed in the show’s credits as a historical adviser. Cryns recently published a nonfiction biography of Adams, titled “In the Service of the Shogun,” for those who would like to know more about what really happened.

Here’s a taste: The famished sailors really did eat the cowhide covers of their ship’s ropes. While rounding the tip of South America, passing from the Atlantic to the Pacific, they also ate penguins. When one sailor got desperate enough to steal bread from the ship’s stores, he was hanged. It was a brutal journey.

Of a five-ship fleet that set out from the Netherlands, Cryns tells us, only one undermanned vessel limped to shore in Japan. Among those who died along the way was Thomas Adams, Will’s brother.

But when Adams met Ieyasu, the change in his fortunes could not have been more complete. Ieyasu took a liking to the Englishman, and placed him among the ranks of Japan’s elite by giving him the status of hatamoto, meaning direct retainer to the shogun. Adams wound up owning several homes, including one whose location is marked by a small monument in Nihonbashi, Tokyo, today.

Eventually, Adams became Ieyasu’s interpreter in negotiations with various European visitors. While the Tokugawa shogunate is now remembered in part for its sakoku policy of national isolation, shutting Japan’s borders was largely the work of Ieyasu’s successors. Cryns depicts Ieyasu himself as an internationally minded leader who thought extensive international trade would be good for Japan.

For example, he hoped that Spain would establish a trading route between the Philippines and Mexico with a stop in Japan. He authorized Adams to go on several trading voyages to Southeast Asia and back. And he was unhappy that Portugal held a virtual monopoly on Japan’s importation of silk from China, believing that more competition would have the benefit of lowering the cost of silk in Japan.

The silk issue is briefly touched upon in the TV show, which features appearances by a large Portuguese ship that made annual trading runs between Japan and Macao. Not included in the show, but described in the book, is an incident in which Ieyasu summoned the captain of that ship to demand an explanation of an incident in which some Japanese who sailed to Macao had died there. The captain refused to appear, enraging Ieyasu and eventually leading to a battle in which the Portuguese ship was sunk.

Writing in a clear, straightforward style, Cryns tells a fascinating story. Watching “Shogun” and reading “In the Service of the Shogun” proves that truth can follow storylines every bit as surprising as fiction.

In the Service of the Shogun

- By Frederick Cryns

- Reaktion Books, 232pp, £16

Top Articles in Culture

-

Junichi Okada Wears Three Hats in ‘Last Samurai Standing,’ Serving as Star, Producer, Action Choreographer in Thrilling Netflix Period Drama

-

Lifestyle at Kyoto Traditional Machiya Townhouse to Be Showcased in Documentary

-

Maison&Objet Kicks off Near Paris with Japanese Lighting Designers’ Installations on Display, Creating Rich Environment

-

‘Jujutsu Kaisen’ Voice Actor Junya Enoki Discusses Rapid Action Scenes in Season 3, Airing Now

-

Prestigious Japanese Literature Prize Names Toriyama, Hatakeyama as Winners

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Univ. in Japan, Tokyo-Based Startup to Develop Satellite for Disaster Prevention Measures, Bears

-

JAL, ANA Cancel Flights During 3-day Holiday Weekend due to Blizzard

-

China Confirmed to Be Operating Drilling Vessel Near Japan-China Median Line

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time