Retrial in Murder of 3rd-Year Junior High School Girl: Wavering Judicial Decisions Show Problems Facing Legal System

15:13 JST, October 24, 2024

Thirty-eight years after the incident, judicial decisions are still wavering between guilt and innocence. It can be said that the issues facing the retrial system are highlighted yet again.

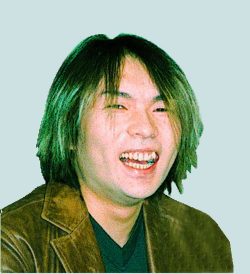

The Kanazawa branch of the Nagoya High Court has decided to begin a retrial for Shoshi Maekawa, who served a seven-year prison sentence, which was previously finalized, over the 1986 murder of a third-year junior high school girl in Fukui City. Maekawa consistently pleaded not guilty and asked for a retrial.

Maekawa’s trial followed an unusual course. He was initially acquitted in his trial at a district court, but a high court overturned the lower court ruling and convicted him. The conviction was finalized at the Supreme Court. There was no clear physical evidence, and his conviction was based on the testimonies of his acquaintances who made such claims as having seen Maekawa “wearing blood-stained clothing after the incident.”

A court once granted his request to begin a retrial, but revoked the decision in response to complaints filed by the prosecution. The decision to start a retrial was then made again in response to his second request. Maekawa, who was 21 years old at the time of his arrest, is now 59 and has served his prison term.

If the prosecution files complaints against the retrial decision this time, the trial will continue further. The current system, which cannot determine guilt or innocence even after such a long period of time, is clearly inadequate.

The high court ruled that there is a possibility that the police induced the testimonies made by the acquaintances, which were the basis for his conviction. If their sense of urgency to arrest a perpetrator led to coercive measures being used in the investigation, it would be totally unforgivable.

The attitude of the prosecution was also problematic. Although prosecutors had investigation materials that contradicted testimonies by the acquaintances, they did not present the materials at the trial and instead continued to make efforts to secure a conviction, apparently out of concern that the materials might have an adverse impact on them. The high court criticized this as “dishonest and sinful misconduct.”

Recently, it has been pointed out that evidence was fabricated by investigative authorities in a 1966 case in which four members of a family were killed in a murder-robbery in Shizuoka Prefecture. The case highlighted the issue of legal delays as Iwao Hakamata, who spent time as a death-row inmate, waited 58 years from his arrest until his acquittal was finalized at the retrial.

There is no legal obligation to disclose evidence in a retrial. The prosecution’s reluctance to disclose evidence has been seen as a problem in the past. It may be obvious that arbitrary disclosure of evidence is one of the factors leading to false accusations.

The prosecution should renew its awareness that evidence gathered through the use of public power is public property. Rules for the disclosure of evidence need to be clarified so that fair retrials can take place.

The system through which prosecutors can file complaints against decisions to initiate a retrial should also be reviewed in order to prevent prolonged hearings.

False accusations not only ruin the lives of innocent people, but also leave the real criminals at large. Reform of investigative methods and the retrial system is urgently needed.

(From The Yomiuri Shimbun, Oct. 24, 2024)

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

Riku-Ryu Pair Wins Gold Medal: Their Strong Bond Leads to Major Comeback Victory

-

China Provoked Takaichi into Risky Move of Dissolving House of Representatives, But It’s a Gamble She Just Might Win

-

University of Tokyo Professor Arrested: Serious Lack of Ethical Sense, Failure of Institutional Governance

-

Japan’s Plan for Investment in U.S.: Aim for Mutual Development by Ensuring Profitability

-

Policy Measures on Foreign Nationals: How Should Stricter Regulations and Coexistence Be Balanced?

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan