11:00 JST, November 22, 2024

Donald Trump has been reelected as U.S. president. I thought he was leading during the campaign, but it was still a great shock when he actually made a comeback.

Since the end of World War II, the world has maintained the United Nations-led principle of not allowing territorial expansion by force. Learning a lesson from the Great Depression, which led to the war, the world shifted to free trade, believing lower tariffs on imports were beneficial. It is the United States that has underpinned this postwar global structure.

However, President-elect Trump’s return to power now makes it increasingly likely that Russia will win the Ukrainian war and that the United States will likely take a big step toward weaponizing tariffs on imports. This means changes that will threaten to fundamentally upend the postwar order of the world.

In Japan, Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba was reelected in a special Diet session on Nov. 11, narrowly managing to stay in power. But the circumstances surrounding his administration remain unchanged, with the ruling coalition being a minority force in the House of Representatives and the outcome of next year’s House of Councillors election looking uncertain. That said, however, I am not that concerned about Japanese politics.

When Yoshihiko Noda, the current leader of the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan, served as prime minister of the government of the now defunct Democratic Party of Japan in 2011-2012, his administration’s policies were not so atypical. The CDPJ does not approve of the 2015 national security legislation and the 2022 Cabinet approval of three key security-related documents, but it does not strongly oppose them either.

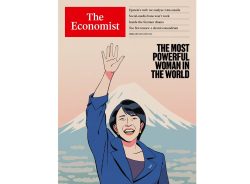

If Sanae Takaichi, a right-wing member of the Liberal Democratic Party, were to rise to the country’s leadership, it would be a cause for concern regarding Japan’s relations with China. As far as foreign and security policies are concerned, there are no big differences between Ishiba and key LDP members other than Takaichi, or with Noda and Yuichiro Tamaki, head of the Democratic Party for the People. In that sense, Japan is the most stable within the Group of Seven major democracies.

Even so, Japan also needs to prepare quickly and substantially for dealing with the second Trump administration. This article will focus on foreign and security policies.

Beef up defense capabilities

The first thing Japan should do is to reinforce its own defense capabilities. To do so, it should push to realize the changes envisioned by the three security-related documents of 2022 — the new National Security Strategy, National Defense Strategy and Defense Buildup Program. Their core goal is to break away from an exclusively defense-oriented policy. Such a policy can be viable as a spiritual goal, but it can never be possible as a real-world approach. For example, the ban imposed by the United States, the United Kingdom and other Western countries on Kyiv’s use of their long-range weapons in Russian territory placed a major constraint on Ukraine’s self-defense.

Secondly, the Japan-U.S. alliance should be strengthened. Ishiba has touched on a possible revision of the Japan-U.S. Status of Forces Agreement. If he wants the Japan-U.S. relationship enhanced on an equal footing, he should rather think of ramping up the role Japan can play in terms of solidifying bilateral ties.

In 1955, then Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu of the administration of Prime Minister Ichiro Hatoyama visited Washington and requested in his talks with U.S. Secretary of State John F. Dulles that the United States withdraw its armed forces from Japan in a certain period of time. Dulles refused, asking if Japan could come to the aid of U.S. forces on Guam if the Pacific island were to come under attack. Shigemitsu said it would be possible, but Dulles then broke off the meeting, saying he could not understand Shigemitsu’s interpretation of the postwar Constitution.

One area where reciprocity between Japan and the United States can be improved is an increased role to be played by Japan’s Self-Defense Forces. The impediment to this was the Constitution — or how the Constitution was interpreted, to be precise.

The third point Japan should pursue in refining its foreign and security policy priorities is to strengthen security cooperation with South Korea, Australia and India as well as the United Kingdom and other European countries on top of the United States.

The fourth is to boost relationships with Southeast Asian countries. I feel uneasy that, among these priorities for security policy, Japan has done the least in this area. I have been thinking for several years now that Japan should exponentially strengthen its relations with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. I envisage the launch of a European Union-like regional institution — a Western Pacific Union.

The Japanese government always emphasizes how important it considers ASEAN, a phrase that now sounds trite. Former Prime Minister Fumio Kishida also pledged to strengthen relations with ASEAN countries but took no notable steps toward greater follow-through.

In September 2023, Kishida said Japan would provide human resources development projects for 5,000 individuals over the next three years, but there has been almost no increase in the number of people admitted to Japan for that purpose.

Seek equal ties with ASEAN

I believe that Japan should seek to develop equal relationships not only with ASEAN itself but also with individual member states, on the basis of long years of economic relations and mutual trust.

China has been actively increasing its influence in Southeast Asia. Within ASEAN, the Philippines is now closer to Japan and the United States, but Myanmar’s turbulence remains far from over, while Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand have proposed becoming members of BRICS, which groups emerging economies.

Indonesia held joint naval drills with Russia early this month. In Laos and Cambodia, China has been significantly expanding its economic presence. Japan-Vietnam relations have weakened a little lately.

All Southeast Asian countries want to continue economic activities with China, while avoiding conflicts with it. At the same time, they want to keep themselves from becoming vassals to China. For that reason, they need the presence of the United States in the region.

Indonesia and Thailand are seeking to become members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. The people of Laos and Cambodia are friendly to Japan, and Singapore and Malaysia dislike China’s high-handed manner.

The Western Pacific region is prone to natural disasters. Japan, the Philippines, Indonesia and Vietnam collaborate with one another in disaster mitigation projects. Further, Japan has provided the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia with coast guard vessels and personnel training courses under maritime capacity enhancement programs. Many public opinion polls conducted in the region cite Japan as the most trusted country.

The EU has systems for dialogue on global and regional issues, involving government representatives and experts. Isn’t it possible for the Western Pacific region to set up a similar system of its own?

The fifth foreign and security policy priority for Japan to pursue is its approach to developing countries in the world. Japan’s official development assistance, provided mostly through the Japan International Cooperation Agency, is trusted by developing countries because of Japan’s unique approach. While attaching importance to such universal principles as freedom, democracy and the rule of law, Japan refrains from imposing them on developing countries. It implements flexible, long-term measures commensurate with local circumstances. Japan’s stance of patiently prioritizing ODA programs for facilitating stabilization and economic growth has delivered favorable results to the point of democratization in some authoritarian countries in Southeast Asia as well.

Developing countries strongly resent the double standards held by developed countries. People in African countries have not forgotten the legacy of British and French colonial rule. They feel bitter that those developed countries, which did nothing to help them when their countries were invaded, have been so vocal about the invasion of Ukraine.

Developing countries’ antipathy toward developed countries is a driving force behind the rise of power of the Global South and BRICS. However, BRICS is short of the strength and ideas needed to lead the world.

When the rule of law is lost to a rule by power in the world, it is the small and poor countries that suffer most. We have to get those countries to come over to our side once again. To that end, Japan should take the initiative in involving other developed countries in redefining universal principles and reaching out anew to developing countries.

The last point is China. It is hard to rapidly overcome the difficult state of Japan-China relations. Japan needs to maintain bilateral relations without provoking China, while making no compromise on the universal principles of freedom, democracy and the rule of law. To do so, Japan should seek steady progress in its relationship with China not only through summits between their leaders but also through working-level contacts and a series of dialogues between their experts, as in the case of the Japan-China Friendship Committee for the 21st

Century.

Shinichi Kitaoka

Shinichi Kitaoka is a professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo specializing in Japanese political and diplomatic history. His previous posts have included Japanese ambassador to the United Nations in 2004-06 and president of the Japan International Cooperation Agency in 2015-22.

The original article in Japanese appeared in the Nov. 17 issue of The Yomiuri Shimbun.

Top Articles in Editorial & Columns

-

40 Million Foreign Visitors to Japan: Urgent Measures Should Be Implemented to Tackle Overtourism

-

University of Tokyo Professor Arrested: Serious Lack of Ethical Sense, Failure of Institutional Governance

-

Policy Measures on Foreign Nationals: How Should Stricter Regulations and Coexistence Be Balanced?

-

China Provoked Takaichi into Risky Move of Dissolving House of Representatives, But It’s a Gamble She Just Might Win

-

PM Takaichi Should Help Young Japanese Break Seniority Barrier to Vitalize Politics

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles May Have Come in Contact with Many People in Tokyo, Went to Store, Restaurant Around When Symptoms Emerged

-

China Eyes Rare Earth Foothold in Malaysia to Maintain Dominance, Counter Japan, U.S.

-

Prudential Life Insurance Plans to Fully Compensate for Damages Caused by Fraudulent Actions Without Waiting for Third-Party Committee Review