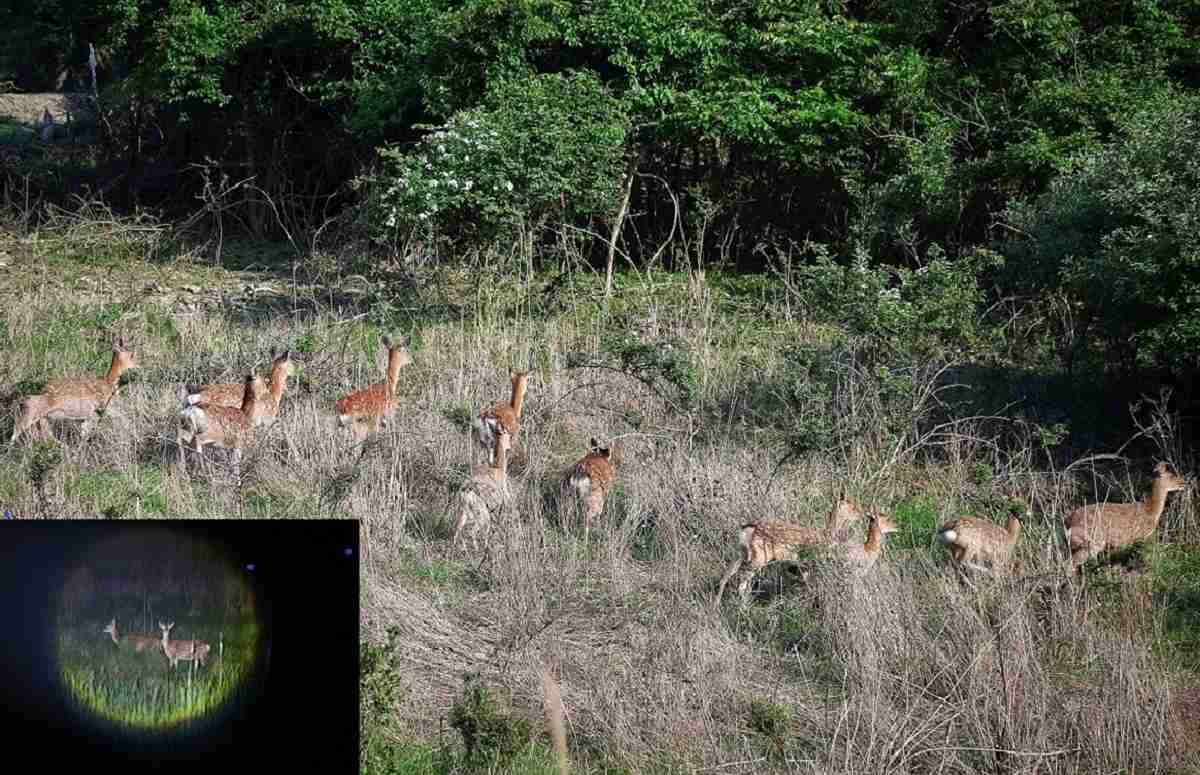

Deer run into the woods on Anma Island in Yeonggwang, South Korea. Inset: Deer roam around the town. Photos were taken between May 22 and 24.

17:43 JST, July 12, 2024

A former vegetable garden, which was abandoned after elderly locals gave up on their fight to protect it from the deer

ANMA ISLAND, South Korea (Reuters) — Under the light of a moon partially obscured by clouds, the eyes of a dozen deer glow uncannily in the dark on South Korea’s island of Anma.

They destroy crops and damage trees in their nocturnal wanderings, but by day the spot is deceptively peaceful, though the humans here must live behind fences, penned into homes and fields, as the animals outnumber them seven to one.

The people of a village nestled beside peaks and a rocky shoreline near South Jeolla Province have all but given up their fight against the deer, whose numbers have exploded since the mid-1980s. Now, they say the only option is to cull the herd.

“I’m sorry to say this, but we need to get rid of them, which is our intention, even if that means we have to kill them,” said Jang Jin-young, 43, one of the leaders of the village, which numbers about 150.

Since the law bans such efforts, he says the government is weighing a petition from the villagers to designate the deer as “harmful wildlife,” rather than livestock, clearing the way for the herd to be thinned by hunting or other measures.

“There are so many deer, I’ve never seen as many as this before,” said Kim Seung-man, who left his job digging up ginseng to anesthetize the deer with blowgun darts so that they can be carried off the island in an effort to reduce their numbers.

Still, sparkling in its serene setting, the island has a lot to offer visitors, said Jang, as the deer are a menace only to residents, particularly the few who still farm.

Spread over an area just slightly larger than Central Park in Manhattan, the deer are now estimated to number 1,000 after years of grazing and breeding freely in the absence of predators.

“I just want all the deer on the island to disappear forever,” said 80-year-old Han Jeong-rye, working in her vegetable garden surrounded by a mesh net that is 1.8 meters high, yet presents no obstacle for the deer, which jump over or rip through it.

“It’s totally useless, I can’t stand it. I’d be happy if somebody could please, please catch them.”

Similar rows of nets, some as tall as 2 meters, and even fences of barbed wire, surround rice seedlings in the island’s fields, but the deer eventually get around them, defeating the efforts of the aging residents.

Left: Flowers grow behind double layered mesh nets, which aim to protect a vegetable garden from the deer. Right: A deer jumps near Kim Seung-man.

The deer came to the island around 1985, when about 10 were brought by three farmers, hoping to harvest their antlers, shed annually and highly prized in traditional medicine.

The budding antler replacements, covered in soft short hair as they grow, are cut and marketed before they harden.

Prescribed along with ginseng and medicinal herbs, they are boiled in water to make a traditional remedy, the cost of which grows with the quality and number of antler slices in the brew.

But dwindling interest in such medicines after the mid-1980s quickly dried up the market for antlers, leading the deer farmers to abandon the animals and leave.

Now the sheer number running wild in wide swathes of the island’s forest makes it practically impossible to harvest antlers, said Kang Dae-rin, who trades them and runs a deer farm near the capital of Seoul.

The weight of numbers also makes it futile to sedate the deer, who also have a severe tick infestation that makes it hard to ship out the animals or their antlers, added Kang.

He has made several trips to gauge the island’s potential as a source of the material.

“There are a lot more of them than I thought,” said Kang, as he waited to board a ferry for the two-hour journey out.

Left: Deer excrement is seen on a hiking trail. Right: Jang Jin-young, a group leader, points at a photo showing a vegetable garden.

Top Articles in Science & Nature

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Japan to Face Shortfall of 3.39 Million Workers in AI, Robotics in 2040; Clerical Workers Seen to Be in Surplus

-

Record 700 Startups to Gather at SusHi Tech Tokyo in April; Event Will Center on Themes Like Artificial Intelligence and Robotics

-

iPS Treatments Pass Key Milestone, but Broader Applications Far from Guaranteed

-

iPS Cell Products for Parkinson’s, Heart Disease OK’d for Commercialization by Japan Health Ministry Panel

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan