Researcher Working to Preserve Natural Disaster Monuments; Disaster Lessons Getting Digitized

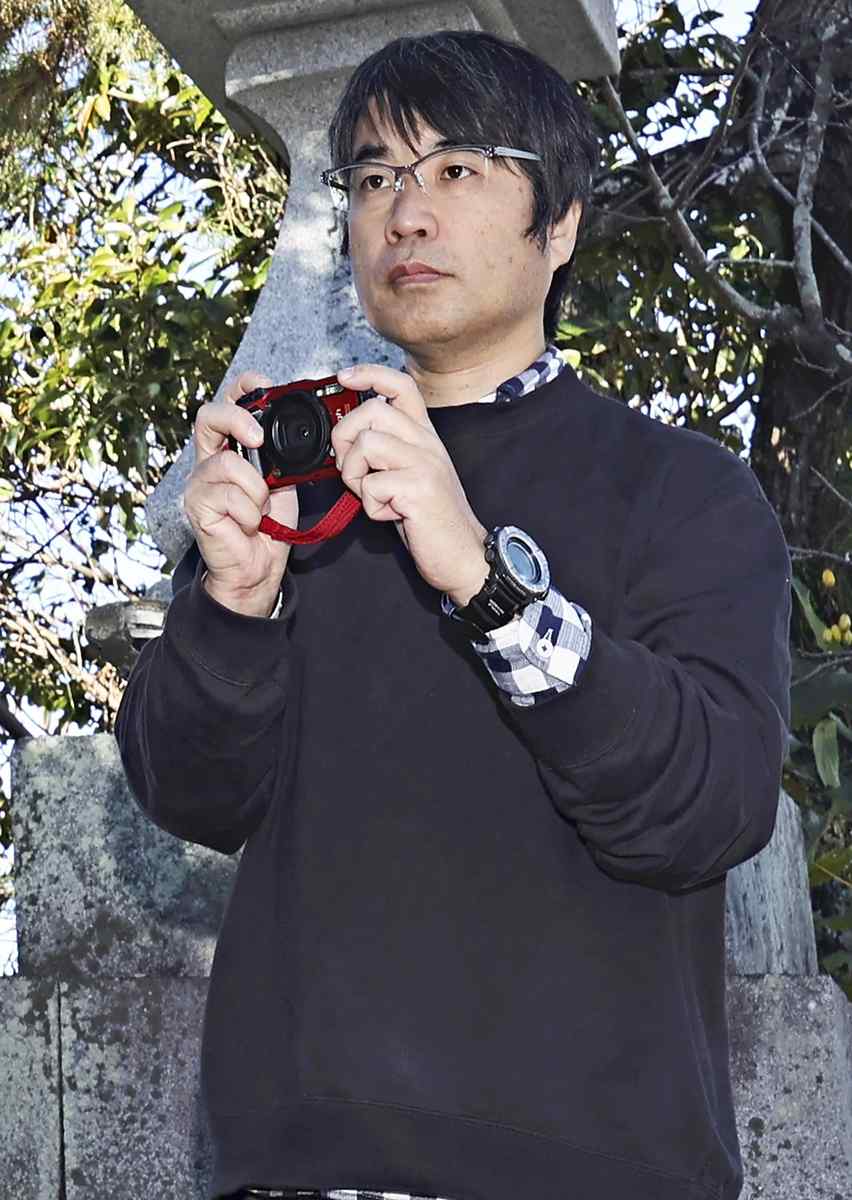

Wataru Tanikawa takes photos of a natural disaster monument to turn it into a 3D model in Konan, Kochi Prefecture.

18:26 JST, April 14, 2025

KOCHI — A researcher is working to preserve natural disaster monuments, which tell the stories of past disasters, by turning them into digital 3D models.

Wataru Tanikawa, 47, of Kochi, a researcher at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC) who studies earthquakes in the Nankai Trough, witnessed from the sea the tsunami caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11, 2011. The experience led him to embark on a research project aimed at warning people about natural disasters. So far, he has digitized monuments in 68 locations in Kochi and Tokushima prefectures, and the data is now being used in disaster preparation education.

Witnessing tsunami

Tanikawa is a specialist in structural geology, which examines seabed rocks and other strata to determine the mechanisms of major earthquakes, and other related areas. He has been a member of JAMSTEC’s Kochi Institute for Core Sample Research in Nankoku, Kochi Prefecture, since 2006.

When the Great East Japan Earthquake hit the Tohoku region, Tanikawa was loading cargo onto the deep-sea scientific drilling vessel Chikyu in Hachinohe, Aomori Prefecture, and felt strong tremors. He and those around him stopped what they were doing, boarded the vessel and evacuated offshore so that the vessel would not slam against the pier in the tsunami waves. It was from there that they watched the first tsunami waves reach the coast.

Cars and containers on the land were overwhelmed and washed away by the tsunami. “I truly felt the incredible energy of the tsunami and the terrible power of nature,” Tanikawa said. He spent a night at sea with more than 100 people, including elementary school students visiting the vessel on a field trip and other researchers.

The experience made him want to directly communicate the the potential danger of natural disasters. He gradually became interested in records of past disasters left by people who experienced them and decided to focus on natural disaster monuments.

Natural disaster monuments

Natural disaster monuments refer to stone structures and monuments recording the details of past natural disasters, such as earthquakes and flood disasters, as well as the lessons learned from them. They also commemorate disaster victims.

The Geospatial Information Authority of Japan created a map symbol to represent natural disaster monuments in 2019. Respective municipalities can apply to register their monuments through the authority, which will include them on its maps once they are registered. As of Feb. 27, 2,269 monuments have been registered.

The authority decided to create the map symbol after a town in Hiroshima Prefecture suffered severe damage in the 2018 heavy rainfall. The town of Saka, which was affected by heavy rainfall in 2018, had a monument recording the damage caused by a flood about 100 years ago, but it was not well known at the time of the 2018 disaster.

Hundreds of photos

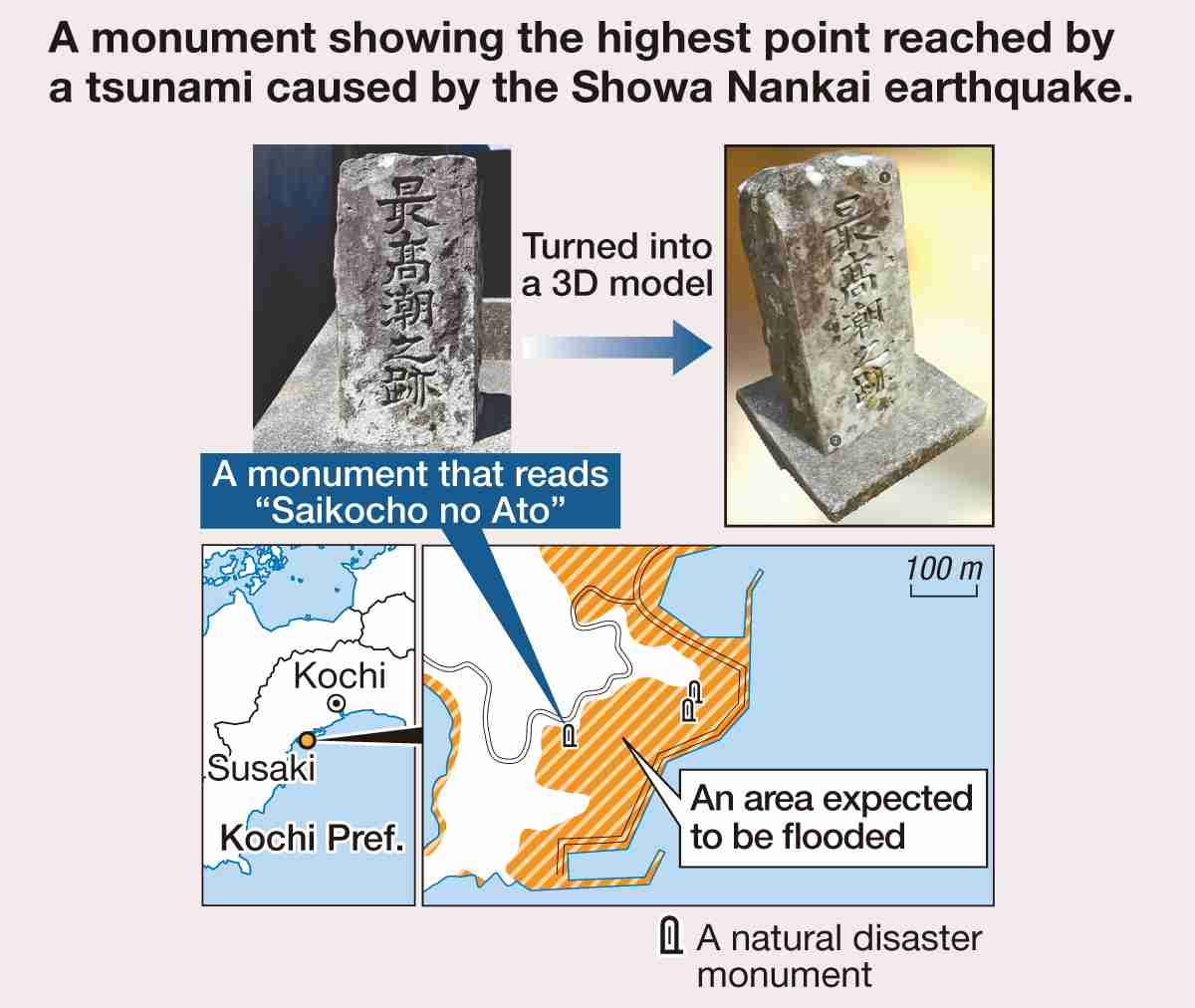

In Kochi Prefecture, there are monuments and stone structures that tell the stories of past earthquakes, such as the 1707 Hoei earthquake and the 1946 Showa Nankai earthquake, and the tsunami they triggered. The monuments record the number of casualties and the areas hit by the tsunami. They also warn people not to let down their guard when it comes to natural disasters.

Local governments are aware of some of the natural disaster monuments, but there are also monuments and structures falling into decay without anyone noticing. Many of them are made of sandstone, which is susceptible to weathering, so Tanikawa began turning them into digital 3D models in around 2015 to preserve the lessons they provide.

He took hundreds of photos of each of the monuments from various angles, uploaded them to a computer and used special software to turn them into 3D models. The method, which requires no direct contact with the object being modeled, does not damage the monuments — unlike the conventional ink-impression method, called Takuhon, which uses sumi ink and paper to transfer inscriptions or images to paper for recordkeeping. His data preservation method allows him to zoom in on hard-to-read kanji characters, making the inscriptions on the monuments easier to understand.

Tanikawa was given a research fund and completed his work at 42 locations in Kochi Prefecture and 26 locations in Tokushima Prefecture by 2019. The data is available in a digital archive on a website run by JAMSTEC. After establishing the archive, Tanikawa went on a business trip to Fukushima Prefecture, where he found monuments detailing eruptions near the prefecture’s Mt. Bandai in the prefecture. He digitally preserved those, too, and made the data available on a different website.

For education

Tanikawa uses the 3D data as material in disaster preparation education, thereby getting more people to know about the existence of the monuments and the locations where they are found. In November, he organized a study event for elementary and junior high school students to visit some of the monuments and experience such activities as turning photos into 3D models, conducting Takuhon ink impressions and designing disaster monuments. Moreover, his data has been used in a class offered by a local museum. “I hope the data will give people an opportunity to think about how to protect themselves from natural disasters,” Tanikawa said.

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Exhibition Shows Keene’s Interactions with Showa-Era Writers in Tokyo, Features Newspaper Columns, Related Materials

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (1/30-2/5)

-

Prevent Accidents When Removing Snow from Roofs; Always Use Proper Gear and Follow Safety Precautions

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (2/20-2/26)

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Japan Institute to Use Domestic Commercial Optical Lattice Clock to Set Japan Standard Time

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan