Fencers using foils, front, and epees, rear, take part in a training session in Chofu, western Tokyo.

17:22 JST, April 9, 2025

I’m around 40 years old, but I recently started a new activity: fencing. That’s right, the sport in which Japanese athletes picked up a heap of medals at the Paris Olympic Games in 2024. It seems that since then, many people have begun showing up on their own at fencing clubs. So what is the appeal of fencing to adults like me who have never tried it before?

After the referee issued the command in French to start, the sounds of blades clanging together and feet quickly stepping back and forth on the floor filled the training hall. A physically demanding sport, a fencing bout will soon have the competitors drenched in sweat, even in winter.

The MNH Fencing Club in Chofu, western Tokyo, eagerly welcomes adult novice fencers. The club has about 50 registered adult members, and since September about 80 people have attended trial lessons, apparently inspired by Japan’s performance at the Games.

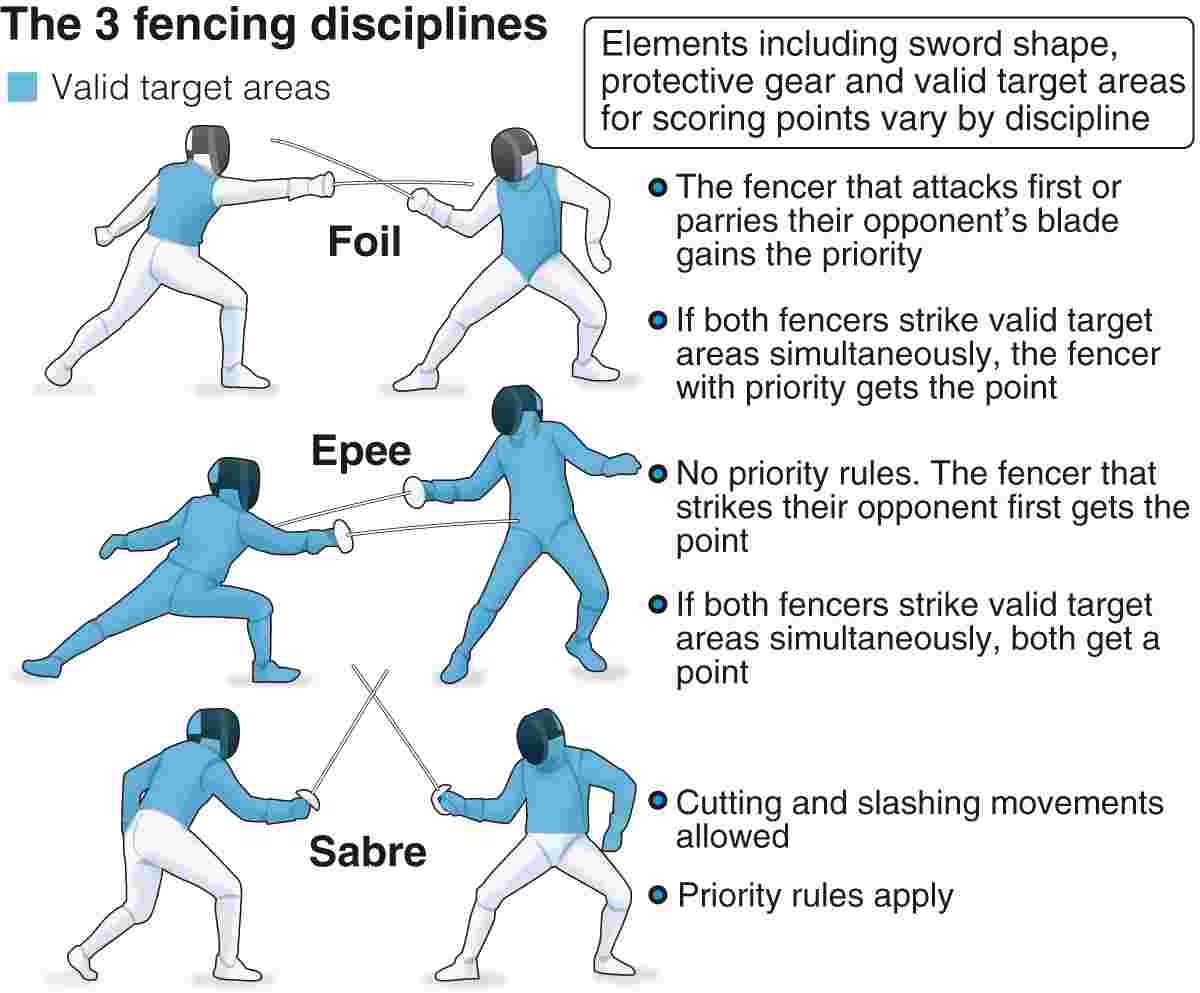

Fencing has three disciplines: foil, epee and sabre. Adults new to the sport are recommended to begin with the epee, and that’s what I started with.

The club has equipment such as swords, masks and uniforms available for rental. All I had to take along was my tracksuit and some indoor shoes. (Buying a full set of equipment will set you back between ¥100,000 and ¥200,000.)

Although fencing had piqued my interest in the past, I had the impression that getting involved in the sport would be quite hard. However, watching the Paris Games inspired me to actually give it a go.

A fencing rookie learns how to hold the sword.

Trial lesson attendees are first given an explanation of the rules and other information, before then practicing basic steps. They then don uniforms and experience their first bout. Although being struck by the sword might look painful at first glance, the slender blade actually doesn’t hurt much at all. The sword’s tip contains a small sensor, and a fencer earns points by hitting the opponent on a valid target area.

“A person who completes just two bouts [of three minutes each] during their first time fencing will often have aching muscles the next day,” said a coach Shu Ohisa, 35. Tactics are such an important part of fencing that it is often dubbed “fighting chess.” Nevertheless, fencing also is considered a sport that even a person who has no confidence in their athletic ability and does not exercise much can easily get into.

About half of the participants in the club’s trial lessons apparently came alone. I asked a few solo fencers about why they came and what they enjoyed about the sport.

A 70-year-old woman from Fuchu first picked up a fencing sword about two years ago. She initially thought of fencing as an activity for her grandchild and came along “intending just to observe.” But she took part in a trial lesson, got hooked and now trains once a week. “It’s a sport even elderly people can do, and it helps to keep me healthy,” she explained. “I even took part in a tournament this month.”

Many people also start fencing for a change of pace from work or study.

A 28-year-old university student from Shinagawa Ward, Tokyo, started fencing after coming to a trial lesson with a friend. “Normally I wouldn’t be able to pick up a sword and try to jab somebody with it, you know?” he said. “It’s a good way to relax.”

A 25-year-old IT engineer from Yokohama, expressed a similar sentiment. “I’m glued to a computer screen when I’m at work, so fencing, which lets me use my body and mind, is a nice break from that,” he explained.

Some local governments also are hoping to harness fencing to energize their communities. Jump-started by its efforts to attract athlete training camps before the Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics, the municipal government of Numazu, Shizuoka Prefecture, has been working with the Japanese Fencing Federation to train and develop fencers.

A council tasked with promoting Numazu as a “fencing city” holds about three events a year at which adults can try the sport and conducts other activities to broaden fencing’s fan base.

Masashi Nagara, who represented Japan in fencing at two Olympics and is involved in the promotion project as an employee of the Numazu city government, hopes even more people will watch the sport and try it themselves.

“There’s even a new version called ‘smart fencing’ in which participants use swords that are soft like a sponge,” said Nagara.

Different rules for each discipline

Fencing is a sport that emerged from chivalry in medieval Europe. Fencers wear protective facemasks and fight with swords while staying on a court that measures 14 meters long by 1.5 meters wide called the piste.

Fencing’s three disciplines each has quite different rules, swords and protective equipment such as masks.

In epee matches, a fencer scores points by using the tip of their sword to touch any part of the opponent’s body, forearms and feet included. The rules are simple, and epee is said to be the fencing discipline with the largest number of competitors worldwide.

Foil and sabre both adhere to priority rules. A fencer gains priority by attacking first or parrying their opponent’s attack.

Japan’s fencing team performed superbly at the 2024 Paris Games and finished with a tally of five medals, including two golds.

Fencing was introduced to Japan in the early Meiji era (1868-1912). Since then, children and newcomers to the sport have typically been taught the foil discipline, so, until recently, this tended to be the event in which Japanese Olympic fencers most stood out. But in recent years, Japanese fencers have increasingly been making their mark on the global stage in the epee and sabre events as well.

Representing Japan even at age 70

Kiyoshi Maeda, managing durector of the Japanese Fencing Federation explained the popularity of fencing in Japan.

In fiscal 2019, about 6,000 people were officially registered as fencers with the Japanese Fencing Federation. In fiscal 2024, that number has jumped to about 6,700. I expect that figure to increase even further in fiscal 2025 due to the impact of last year’s Paris Olympics.

Many of Japan’s fencers have been involved in the sport since they were students, but more than a few people started as adults.

I personally began fencing when, at age 55, I was invited to join in by a friend in France, where I had moved for work. These days, I train once or twice each week.

It isn’t uncommon for people to leave off fencing for a while and then pick up their swords again years later, so it’s attracting attention as a sport that can be played throughout one’s life. So-called veteran fencers aged 40 and above even have their own tournaments, and participants in this age bracket at international competitions wear national team uniforms bearing the Japan logo, just like Olympic athletes. Even fencers aged 70 or older can take part.

The federation’s website has a list of training venues across Japan, and some clubs hold events at which people can take a crack at fencing. I encourage anybody curious about fencing to get in touch with their local club.

A highly tactical leisure activity

When I watched other fencers locked in combat, I would often wonder things like, “Why don’t you attack that target?”

But when I was actually on the piste and trying to counter my opponent’s tactics, I felt like my head was about to start billowing smoke.

Even when I wanted to defend against their attack and get in position to launch my own attack, I’d inadvertently thrust my sword forward first. My coach instructed me to “Be patient!” It’s remarkable that people of all ages get along well while thrusting swords at each other every week. I definitely recommend fencing as a great leisure activity you can join on your own.

—Kisaki Ozawa

Top Articles in JN Specialities

-

Exhibition Shows Keene’s Interactions with Showa-Era Writers in Tokyo, Features Newspaper Columns, Related Materials

-

The Japan News / Weekly Edition (2/20-2/26)

-

Step Back in Time at Historical Estate Renovated into a Commercial Complex in Tokyo

-

Senior Japanese Citizens Return to University to Gain Knowledge, Find New Career, Make Friends

-

“The Tale of Genji” Back-Translation Project Led to Touching Encounter with Keene; Poet Sisters Recount Memories of Scholar at Packed Talk Event in Tokyo

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan