Kate Winslow and Maria Horn continued with their end-of-year plans, even though little was normal.

12:39 JST, June 24, 2024

ROTTERDAM, N.Y. – When busloads of migrants suddenly arrived at a motel in this town of 30,000 last July, the word spread fast.

Local officials reacted with fury. Residents packed a town meeting to express their outrage. Members of a local Facebook group warned darkly of a potential rise in crime.

Shannon Shine, by contrast, got to work.

The superintendent of the school district, Shine had some basic questions. Were there school-age children in the group? What were their grade levels? Did they speak English?

The answers left him shaken. It turned out there were 72 children. Only two had any proficiency in English. Many had been traveling for months.

“I thought, okay, this is outside my experience entirely,” said Shine, 54. “This is outside all of our experience.”

The story of what unfolded at Mohonasen Central School District over the past year is a dramatic example of how communities across the country have grappled with a wave of new arrivals, many of them seeking asylum.

Many have headed to cities with a history of welcoming immigrants, such as New York and Chicago. But they’ve also traveled to small towns and rural areas, presenting a fresh challenge for local governments, nonprofits and schools.

Mohonasen, a school district in Upstate New York more than 2,000 miles from the southern border, was unprepared for the migration crisis to arrive on its doorstep. Before last year, just 2 percent of its students were English-language learners; most of those spoke Chuukese, a Micronesian language spoken by a small immigrant community in the area.

When an influx of children from migrant families arrived weeks before the start of school, the district scrambled to adapt. Teachers at its four schools took on new roles. Social workers provided vital help with everything from winter boots to medical care.

The school district tried to be a source of stability in the lives of its newly arrived students, many of them from Venezuela, Ecuador and Colombia. When the migrant families were abruptly forced to move out of the motel where they were staying one evening in May, Shine rushed to the spot to see how he could help.

“These are our students,” he said. “We’ll take care of them.”

That commitment would be tested in ways Shine never imagined.

Mrs. Winslow’s class

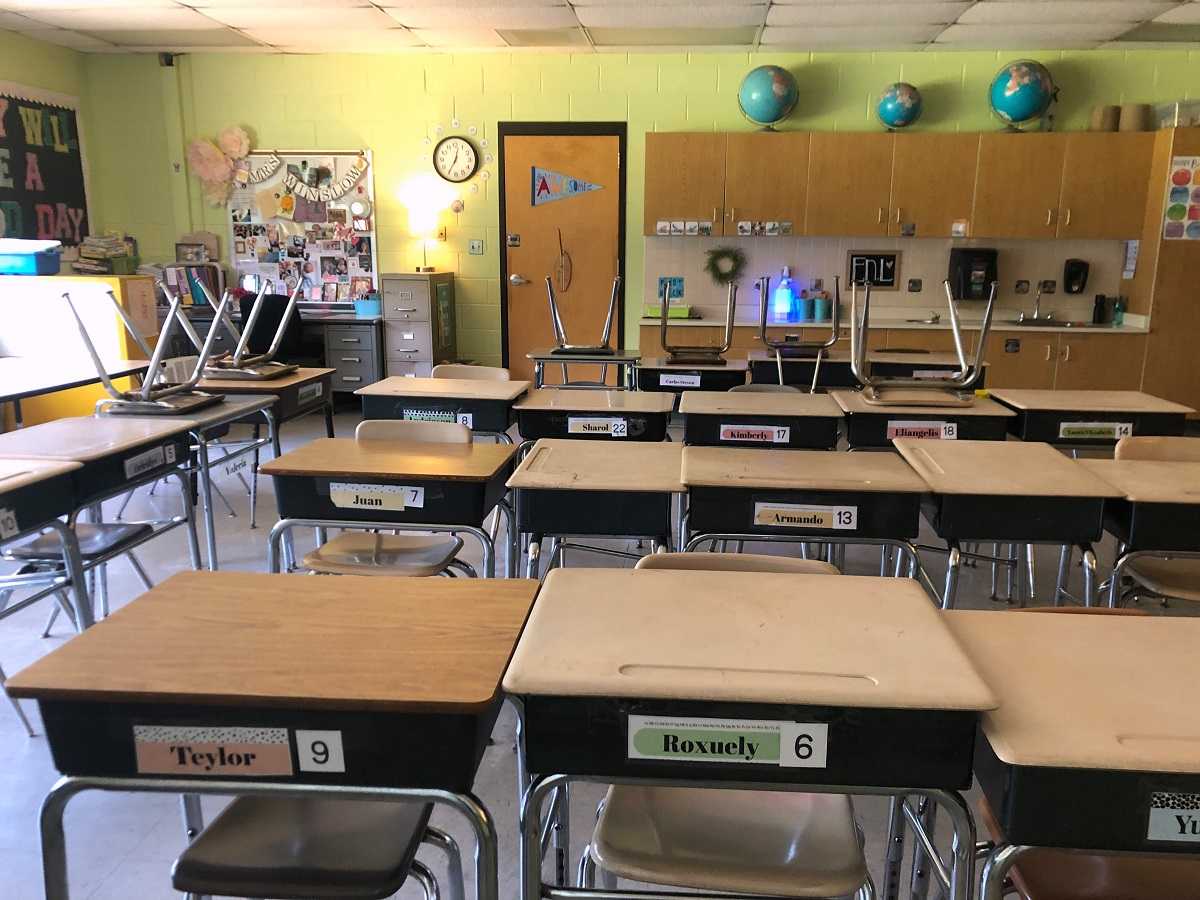

In Kate Winslow’s classroom, students have desks with their names on them.

One afternoon at the end of August, Kate Winslow stood in a classroom at Pinewood Intermediate School in Rotterdam and took a deep breath. The room was freshly scrubbed, the decor colorful without being overwhelming. She knew from her time as an exchange student in Spain that learning a new language was its own kind of sensory overload.

Just days earlier, a district administrator had called Winslow and told her she would be teaching a classroom of more than 20 migrant children when school started in a week.

Winslow, 40, was filled with panic. She had spent nine years teaching English learners at Pinewood, helping them in small groups both inside and outside their regular classes. But she had never had her own classroom, let alone one with so many students with so little exposure to English.

The students and parents visited Pinewood for the first time that afternoon. When they arrived, they walked down hallways decorated with student artwork and marked with faux street signs – Respect Drive, Kindness Crossing, Honesty Lane.

As the families filtered in, Winslow felt her cheeks warming as she struggled to keep up with the rapid-fire Spanish directed her way.

A 9-year-old named Kimberly from Ecuador with wavy black hair and a shy smile ran over and slipped her hand into Winslow’s. She gazed around the room. “Esta es la escuela de mis sueños,” she said. This is the school of my dreams.

The gratitude from parents and children was palpable. “They were just like, ‘Wowww,’” Winslow said. “They thought that they were somewhere.” She thought to herself: All right, you can do this.

It wasn’t only Winslow who was out of her comfort zone. District administrators had asked state experts for advice and raced to double the number of teachers who specialize in English-language learners from roughly three full-time positions to six. The extra teachers and support staff cost $400,000, all of which would be reimbursed by state and federal funding.

Administrators decided to create two “sheltered” classrooms for the migrant students to acclimatize them to their new schools. One was at Bradt Primary, a kindergarten-to-second grade school. The other was Winslow’s classroom at Pinewood, with students from third to fifth grades. There were also some at the middle and high school in the 2,800-student district, where nearly half the pupils are considered economically disadvantaged.

Sometimes students said things that shocked Winslow and her teaching assistant Maria Horn, 55, a brand-new hire with a passion for education who had immigrated to the United States from Ecuador nearly three decades earlier.

A 9-year-old boy had to leave the bathroom door open because he struggled with claustrophobia. He said it had been that way ever since he was put in “una caja” – a box, cold like a refrigerator, on his journey north. Winslow and Horn didn’t pry further.

A 10-year-old girl from Venezuela hadn’t attended school consistently since 2021, when her family fled their home country, first for neighboring Colombia and then the United States. Many of the students were testing below grade level in literacy and math in their native language of Spanish.

Their needs were unlike those of other students. Elizabeth Haynesworth, the school’s bilingual social worker, helped coordinate a donation drive for boots and jackets when temperatures plunged in the winter. She arranged transportation from the motel where the migrants were staying during parent-teacher conferences and acted as a go-between for medical appointments.

The families had been bused to the Super 8 motel in Rotterdam from New York City, 160 miles away, part of an effort by Mayor Eric Adams (D) to shift new arrivals elsewhere in the state as the city’s shelter system came under severe strain. City officials promised migrants several months of housing and meals, plus help with their asylum process, paying a company called DocGo to operate the program.

The number of migrants who arrived in the Rotterdam area last year was roughly equivalent to the prior nine years combined, according to a Washington Post analysis of federal immigration court records.

Rotterdam is a predominantly White town with per capita incomes slightly below the national level. While some locals – including a number of parents in the school district – were hostile to the new arrivals, others jumped in to help them. “It’s America in 2024,” said Jason Thompson, Pinewood’s principal. “I am never going to say that it was kumbaya.”

As the year progressed, Winslow’s classroom was in constant flux. Sometimes students would leave at the end of the day, never to return. Winslow and Horn would later learn that their families had moved outside the district. A steady trickle of new students also continued to arrive from New York City.

For the district’s migrant students, there were small victories. The mother of a child from Ecuador who spoke on condition of anonymity because of the precariousness of her family’s housing described with pride how her eighth-grader was named to the honor roll. Two newly arrived students joined the high school’s nationally ranked “drone soccer” team, a sport where players pilot drones on an enclosed pitch.

By May, six of Winslow’s students moved out of her “sheltered” classroom and joined their mainstream peers. One of them was Kimberly, the student who had taken Winslow’s hand back in August.

Kimberly’s journey

Kate Winslow, right, has taught English-language learners at Pinewood Intermediate for nine years. She had never had her own classroom, let alone one with so many students with so little exposure to English.

For Kimberly, Pinewood was a revelation. She marveled at its cafeteria, its playground and its lack of uniforms. Her school in Ecuador had 40 students to a classroom with a single teacher. Here she had different teachers for science, art and gym.

She found the classrooms beautiful. In Ecuador, there “were just chairs and tables,” she said in Spanish. Mrs. Winslow’s room was large and decorated and even had toys. Kimberly’s desk had her name on it.

It was also a place where she felt safe. Her family – father Jorge, mother Mayra and two younger sisters – fled Ecuador after Jorge was assaulted and threatened by gangs, which have grown increasingly powerful, destabilizing the country. (Kimberly and her parents spoke on the condition that their last names not be used.)

After a 21-day journey north by foot and bus that took them through the treacherous Darien Gap, the family turned themselves over to border authorities in Arizona. They made their way to a migrant intake center in New York City, where they spent two nights sleeping on floors and in chairs, Mayra said, before they were given the option to go to a hotel three hours away.

The Super 8 had bedbugs, and the food provided by the contractor hired by the city to run the program, DocGo, sometimes sickened her children, Mayra said. But it was a start. With the help of a nonprofit, they applied for asylum.

DocGo said in a statement that it provides fresh meals that meet food-safety guidelines and works to resolve pest control issues. Attempts to reach the owner of the Super 8 by phone and text message were unsuccessful.

Jorge, 28, found occasional landscaping jobs. Other parents cleaned bathrooms, installed roofs, ripped out ventilation systems and served customers at fast-food outlets. Jorge and Mayra, 27, just wanted steady work so they could repay the debts they had incurred to come to the United States.

For Kimberly, a careful dresser who loves listening to Olivia Rodrigo and Taylor Swift, it had been a year of discovery and accomplishment. She went ice skating for the first time (“I didn’t know you could spin on ice!” she said). In April, she won her school’s monthly award for the student that embodies a certain value – in her case, citizenship.

At first, she said, it was hard to adjust to taking all her classes in English. But “now I have a little more confidence.”

Then, one Wednesday evening in May, the family’s world was turned upside down.

A few hours after Kimberly returned to the motel on the school bus, the nearly 160 migrants at the Super 8 were told they had to vacate the building immediately because its sprinklers were defective.

In a chaotic rush, families began filling plastic bags with their possessions. Jorge called Anita Nasuto, a local woman who had befriended the family, and told her they were being thrown out. Nasuto rushed over to the motel, as did Shine, the school superintendent, and Haynesworth, the social worker at Pinewood.

Haynesworth told Winslow that she managed to hug some of their students. A boy from Ecuador came running over. He asked, “Am I going to get to say goodbye to Mrs. Winslow? I know how much she loves me and I know she’s going to be worried.”

Winslow was frantic. “I’m so scared they won’t come back,” she wrote in a text message that night.

Shine sent an email to his staff at around 8:30 p.m. describing the situation as “very dynamic.” The affected students “will likely be anxious or upset if/when they are in school tomorrow and in days to come,” he wrote.

It was not until after midnight that some families were transported to different hotels miles away. Some of them were moved repeatedly in the ensuing days, including while children were at school, sparking a rush to figure out how to reunite them with their parents after dismissal.

(DocGo said the fire-safety system at the Super 8 was inspected and deemed compliant days prior to the order to close the hotel. On May 15, the fire department identified a new issue with the sprinkler system, the company said. The Rotterdam Town Supervisor did not respond to questions.)

By the following week, nearly all the families were at a different motel in Latham, N.Y., more than 10 miles away from Rotterdam. Outside the hotel, Diego Garcia, an Ecuadorian asylum seeker whose sons study at Pinewood, said his boys were exhausted by the late nights and constant moving.

Behind the scenes, Shine and Katie Lossi, the district administrator in charge of English-language learning, raced to arrange alternative transportation. A former bus driver volunteered to come out of retirement to drive the new route. Lossi rode along to make sure everything went smoothly on the drive, now half an hour each way.

A trip to the science center

Teaching assistant Maria Horn, 55, a new hire who had immigrated to the United States from Ecuador nearly three decades earlier, speaks with a student.

About two weeks later, the families were moved yet again, this time to a motel in Albany about 12 miles from Rotterdam. They were told they could stay there until June 28, a few days after the end of school year. Then they needed to find somewhere else to live.

William Fowler, a spokesman for Mayor Adams, said the city and DocGo had worked hard to ensure that the families could stay in the area through the end of the school year. “We’re subject to who’s willing to partner with us and who’s willing to take on this work,” he said.

Inside Winslow’s classroom, the children were increasingly upset, with behavior to match. “We’re trying to run a therapeutic classroom at this point,” Winslow said. That meant lots of down time and not disciplining students for every outburst.

The teachers kept going with their end-of-year plans, even though nothing was normal. Winslow and Horn took their students to Adirondack Animal Land, a zoo, and the science center in nearby Schenectady. Inside the planetarium, the students oohed and aahed, craning their necks and pointing as the sky rotated. They shouted questions. “Is that Saturn?” asked one boy.

Later, Winslow and Horn watched their students delight in displays demonstrating the power of air pressure and the workings of a worm gear invented by Leonardo da Vinci. After all the turmoil, it was good to see them just being kids, Winslow said.

It wasn’t clear if any of the children would be back at Mohonasen in September. That included Kimberly. Her family had an unusual stroke of luck: With Nasuto’s help, they found an apartment a few miles away from Rotterdam. But the housing was in a different school district.

Some families were counting down the days remaining in June with dread. A 33-year-old mother of four from Colombia with two students at Pinewood said her children were distressed by the idea of moving, but the family didn’t have the money to secure housing. It was possible they would end up in New York City, right back where they started a year ago, asking for shelter.

“It makes me sad to see my children like this,” she said at the end of May, speaking on condition of anonymity because of the insecurity of her situation. “The doors are closing on us.”

When the students returned from the science center, they piled out of the bright-yellow school bus and through the main door at Pinewood. It was time for lunch: They turned right into the cafeteria and lined up for slices of cheese pizza and small containers of fat-free chocolate milk.

There was still some computerized testing to administer that afternoon, but first Winslow took her students outside for recess. A group of boys started a vigorous game of soccer. Two girls sat at a picnic table with Winslow to draw while another headed to a nearby slide.

The children kept returning to Winslow as though drawn by a magnet, asking her questions, touching her arm. Through everything, she said, they had been her grounding force. On the front of her daily planning notebook, she had taped messages they had written to her.

“Thank you for teaching us new things,” read one in black marker, “and loving us very much.”

Top Articles in News Services

-

Survey Shows False Election Info Perceived as True

-

Hong Kong Ex-Publisher Jimmy Lai’s Sentence Raises International Outcry as China Defends It

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Touches 58,000 as Yen, Jgbs Rally on Election Fallout (UPDATE 1)

-

Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average Falls as US-Iran Tensions Unsettle Investors (UPDATE 1)

-

Trump Names Former Federal Reserve Governor Warsh as the Next Fed Chair, Replacing Powell

JN ACCESS RANKING

-

Producer Behind Pop Group XG Arrested for Cocaine Possession

-

Japan PM Takaichi’s Cabinet Resigns en Masse

-

Man Infected with Measles Reportedly Dined at Restaurant in Tokyo Station

-

Israeli Ambassador to Japan Speaks about Japan’s Role in the Reconstruction of Gaza

-

Videos Plagiarized, Reposted with False Subtitles Claiming ‘Ryukyu Belongs to China’; Anti-China False Information Also Posted in Japan